If you ever want to catch a banker out, ask them what the fourth-biggest financial centre in the world is. The answer? It is not Frankfurt, Hong Kong, Geneva or Shanghai, but Edinburgh. Add in Glasgow, which is big in asset management, and Scotland has one of the most important financial services industries in the world.

Those troublesome facts for Scottish banks

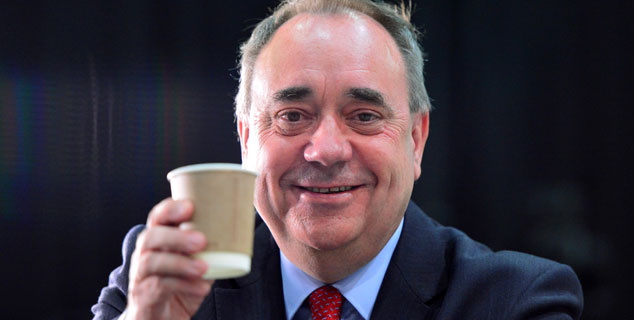

But right now that is surely under threat from the Scottish National Party’s “perma-frendum” campaign – the party’s apparent determination to hold regular votes on independence until it gets the “right” result. Only last weekend, former SNP leader Alex Salmond was promising another vote. It is, of course, less than a year since Scotland voted, by a clear and decisive margin, to remain part of the Union. Still, the SNP has conveniently brushed that aside, the same way that it brushes aside many of those troublesome things called “facts”.

With a dominant majority in the Scottish Parliament, which is only likely to grow at next year’s elections, it will probably get its way. And if the SNP does not get the result it wants in 2019 or 2020? Then it will start campaigning for another round in 2025, until it does get its victory. Scotland now seems set on a permanent referendum campaign, with another vote always looming on the horizon.

That, of course, has implications for business. At the time of the last referendum, plenty of companies said the uncertainty was damaging. A few brave commercial leaders even risked the wrath of the Nationalists by warning that they might have to leave Scotland if it chose to quit the Union. A one-off referendum was one thing, of course.

Plenty of companies might quite reasonably decide that a single vote was acceptable, and they would make whatever decisions were necessary depending on the outcome. But a “perma-frendum” is surely very different. It means that banks and fund managers headquartered in Edinburgh or Glasgow have the threat of a sudden change in nationality – with all that that implies for regulation and funding – permanently hanging over them.

An opportunity for the Square Mile

That is a lot of uncertainty for a company to cope with. That is all the more true when you consider that an independent Scotland would be likely to have a very left-wing government, intent on driving taxes higher, with no real clarity on what its currency would be. It would also be left having to cope with a falling oil price, devastating one of its main sources of tax revenue.

What kind of responsible financial firm would want to remain in a place where there is this constant threat of breaking away, especially considering that most of its business is done outside of Scotland itself? At the very least, they will have to consider relocating to somewhere where they can be sure of which country they will be based in for the next three to five years.

That is surely an opportunity for the City of London – and some of the other big English financial centres. While Edinburgh and Glasgow’s finance firms trade globally, most of them address the British market, and are used to being regulated by the Bank of England. So while they would be free to move anywhere, England would be the most natural destination.

It would help, however, if they were encouraged. The rest of the UK should be campaigning to bring them south. The big fund managers could be tempted to move to London, where they already do a lot of their work. The back office work, based mainly in Glasgow, could be persuaded to move to Birmingham, Manchester, or Bristol – all of which offer comparable costs for renting offices and hiring staff, have plenty of law firms and accountants to work with, and even have slightly better weather.

Lay out the welcome mat

How would that be done? The City of London Corporation could offer a five-year rates exemption for any company moving from Scotland to the Square Mile. That could help change a few minds. Birmingham or Bristol could offer the same deal – and perhaps even make it ten years, given that they are less well-established than the City.

If Chancellor George Osborne really wanted to make mischief, he could throw in tax incentives or regional grants for those moving south. And as part of the renegotiation of the UK’s membership of the European Union, Osborne could promise to protect the City – a deal that would apply to UK firms, but of course not those based in an independent Scotland.

True, that will annoy SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon. But so does just about everything. And who knows? It might focus a few minds among Scottish voters, reminding them that, while it was perfectly legitimate to have one vote on independence, to hold one every few years is simply ridiculous. The damage to the economy will be far too great.

The finance sector will probably flee a politically unstable Scotland anyway – it is hard to see any business feeling comfortable in a country that is so divided on something so fundamental. So it may as well come to London and other English cities, rather than elsewhere in Europe – and the City in particular should lay out the welcome mat.