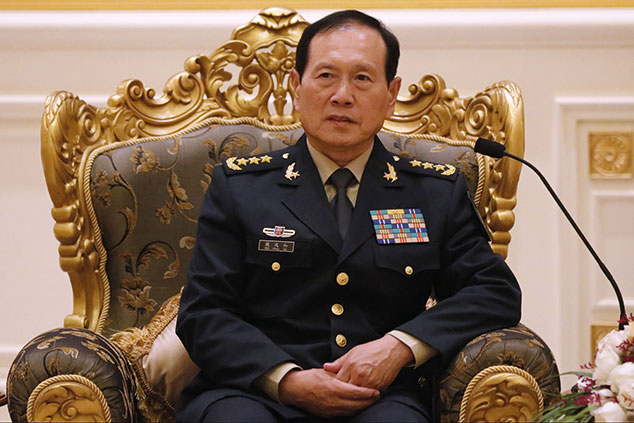

On the 30th anniversary of the “bloody crackdown” on protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989, a top Chinese official has attempted to justify the action, says Alessio Perrone in The Independent. During a speech in Singapore, defence minister Wei Fenghe said that the massacre, which resulted in the deaths of thousands of unarmed protestors, was the “correct policy” to deal with “political turmoil”. Even acknowledging that the massacre took place is rare for the regime, and reports on what took place are “heavily censored” on the mainland. Every year, police detain “dozens of activists, journalists and critics in the run-up to the anniversary” of the protests.

The government’s refusal to apologise is an “ice-cold reminder” that China “is still ruled by a regime ready to use force to stay in power”, says The Times. There were hopes in the West that economic reform would “endow the regime with a sense of global responsibility” and it would reform along liberal lines, but the country has instead simply “developed a version of the autocrats’ social contract” – where people give up their freedom in return for a promise of improving living standards. So, politically, China remains “a Leninist state afraid of challenge from the dead as much as the living” – where dissidents are “locked away”, Uighur Muslims “incarcerated in sinister re-education camps”, and a surveillance state set up that “places people in a virtual cage”.

While political reform seems as distant a prospect as ever on the mainland, things also seem to be getting increasingly worse in Hong Kong, the former British territory handed over to China in 1997, says The Wall Street Journal. In theory, the 1997 handover agreement guarantees that the Chinese government will respect civil liberties until 2047. Tens of thousands of Hong Kong citizens take advantage of the more liberal atmosphere to attend vigils to mark the massacre. However, China’s “growing economic and political clout” has “increased fears about eroding freedoms decades before that deal expires”. Indeed, there are worries about proposed laws making it easier to extradite people to China, as well as future plans to outlaw “seditious remarks and actions against Beijing”.

Despite the political repression, however, the Chinese people seem willing to put up with the regime as long as it delivers economic prosperity, says Lucy Hornby in the Financial Times. Indeed, if 30 years has taught us anything, it’s that “a prosperous middle-class China” will not necessarily turn against the ruling Communist party, as many outside observers had expected. Chinese people in their teens and 20s “have no direct experience of the inflation, shortages and corruption that brought their parents’ generation on to the streets”, and a sense that China is finally the equal of the US has dampened demands for democracy.

Still, things could change quickly, and there are signs that “the social compact in which obedience is secured by better living standards is fraying as growth slows”, says Peter Sweeney for Breakingviews. Rising inequality, low wages and long hours are creating the conditions for mass protests, especially considering China’s government “is again asking youth to bear the brunt of the economic burden, from bad debts to the trade war”. The legacy of its repressive one-child policy also means that, while China still has lower living standards than Russia, it nevertheless “has the demographic profile of a far richer country”, storing up problems for the future.