The recession is tightening its grip. This week, Wednesday alone saw more than 4,000 job losses as media, technology and pharmaceutical groups axed workers. Virgin Media is cutting 2,200 jobs, and Glaxosmithkline, Yell and Taylor Wimpey are also retrenching. The economy is now losing 1,000 jobs a day and the claimant count is almost at one million for the first time since 2001, after the biggest monthly rise in 16 years in October.

This is “the tip of the iceberg”, given that unemployment is a lagging indicator and rising so sharply early in the downturn, said Vicky Redwood of Capital Economics. The claimant count is likely to rise to two million and the overall jobless rate to 10.5% (from 5.8% now) before the nastiest recession in 25 years is over. Dwindling demand bodes ill; note that year-on-year retail sales actually fell marginally last month, “an extremely rare event”, as Helen Dickinson of KPMG pointed out. Higher unemployment will continue to put pressure on house prices.

More interest rate cuts ahead…

The Bank of England now thinks inflation is on track to fall to 1% in two years as the economy shrinks, which implies scope for further reductions in interest rates. But this is likely to be a case of pushing on a string. With rattled banks attempting to rebuild their balance sheets, not least because as the recession bites there will be further losses ahead, and money markets still seized up, cuts are unlikely to be passed on. Following the latest large cut lenders have kept pulling deals off the market (the number of deals has shrunk by 800 since last week, said Moneysupermarket.com), repriced tracker mortgages upwards and tightened conditions. Credit availability, not price, is the problem. Nor are fearful consumers or firms in a mood to borrow.

…and a plunge in sterling?

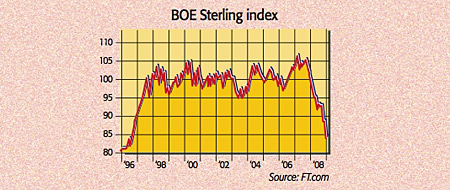

Hence the need for a “second front” to fight recession, as Gary Duncan put it in The Times: a stimulus package. But that requires even more borrowing, which is already expected to rise to £100bn in 2010-2011 from £60bn this year. Yet now it seems that international investors are tiring of funding Britain’s profligacy. Bank of New York Mellon says outflows of international funds from gilts and corporate bonds since 10 September have offset 75% of the inflows since 2004. This has sent the Bank of England trade-weighted sterling index to a 12-year low. A vicious circle could set in, with the sliding pound deterring even more investors from holding sterling assets.

Even absent a sterling crisis, which would drive up inflation and interest rates in the medium term, the Government “may have to get used to paying a lot more for its money”, said Jeremy Warner in The Independent; yields would have to rise to entice capital. Even higher borrowing costs imply steeper tax rises later. “Bust is following boom,” said Ian Campbell on Breakingviews. There’s “no easy way out”.