Spring is often said to be the best season to be in Shanghai, sandwiched as it is between a winter of near-Siberian winds and a hot, humid summer. And as far as investors are concerned, it seems to have come early this year.

The CSI300 has bounced 32% since the beginning of January, making it the world’s best performing market by a mile. The reason? After probably growing at around 0-4% last quarter (using the same method of measuring as the US, rather than the headline numbers), a rush of data has suggested that China’s economy may be on the verge of rebounding very rapidly.

The only problem is that once you look closely, there’s less to this than meets the eye. Yes, any suggestion that China isn’t joining the rest of the world in freefall is welcome. But I see little to change my view that the next six months will be as bad as the last three…

It’s too early to call the bottom

Most of the indicators that investors are looking at don’t really tell us very much. Yes, the purchasing managers’ indices have ticked up slightly. Steel traders are restocking inventories. The rate of decline in construction looks as if it may be slowing.

But all these indicators remain very depressed. And the slight improvements could easily be noise – you’ll remember how every little bounce in American housing data over the last three years was greeted as a sign that the bottom was near.

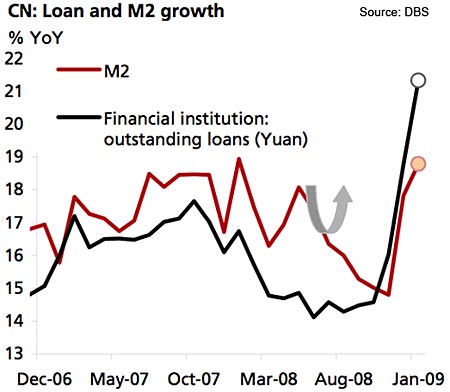

More significant is the huge surge in new lending by Chinese banks. Since the government removed loan quotas and instructed banks to keep lending, loans have been rising strongly, culminating in a 21.3% year-on-year leap last month, and M2 money supply has risen correspondingly.

It’s certainly encouraging that Chinese banks are able to lend, but it would be unwise to read too much into a leap as large as this. Firstly, the breakdown of the lending suggests that much of it is short-term loans and bill financing, which is largely working capital for firms rather than long-term financing for investment.

Obviously, this is important in terms of keeping cash-strapped businesses operating – it’s just the kind of help that smaller firms in the West are lobbying their governments for. But it isn’t creating new jobs and boosting investment, which is key when it comes to lifting growth.

Secondly, we don’t know how much of this is replacing non-bank lending. China has a substantial shadow banking system of unauthorised lenders and off-balance sheet lending by banks trying to get around their loan quotas. Some estimates peg the size of this system at around 30% of conventional lending, so it’s significant by any standards. Some of the new bank lending may be people replacing unauthorised loans with bank debt or banks bringing loans back on balance sheet, rather than new lending.

Lending in China is clearly holding up, in contrast to most of the world. But the latest numbers probably make things seem more robust than they are.

The shipping rebound is more about supply than demand

The other index that investors are getting excited about is the Baltic Dry Index, which measures the cost of shipping dry bulk commodities such as iron ore. After plummeting 95% since the summer, it has now bounced 200% in the last few weeks.

But again, taking this as evidence of resurgent Chinese demand for commodities may be reckless. Speculators had booked ships with the intention of flipping the contracts; once rates crumbled they abandoned these contracts, dumping a large number of unbooked ships on the market and forcing down spot rates.

That depressed the BDI to exceptionally low levels. But with that excess supply fading – helped by large numbers of vessels being laid up because of low rates – the glut of ships has reduced a little. Lower supply rather than higher demand is probably what’s driving up shipping rates.

Trade data is getting worse

What’s more, other news from China has been unequivocally weak. Exports were down 17.5% in January; it’s hard to see the economy strengthening before they stop falling. What’s more, the 43.1% plunge in imports doesn’t suggest strengthening domestic demand. To be fair, much of this was due to falling commodity prices and lower demand for goods for processing and re-export – but there were still outright falls in capital goods imports from Europe, which suggests weakness in investment demand. Yes, this data was affected by the Chinese holiday – but even allowing for that, this data was weak.

There are some other positive signs. Consumer price inflation is falling, but mostly in food and goods that are subject to government price controls. This will increase real incomes and help support consumer spending.

If deflation really takes off in manufactured goods it will hurt company profits, which would be less good for investment (especially since the majority of Chinese firms’ investment is financed from retained earnings rather than debt). But so far corporate investment seems to be holding up relatively well, as the chart below shows – indeed, once you allow for inflation, the rate of growth seems to be accelerating.

Overall, the picture from China is mildly encouraging: if underlying lending, investment and consumption hold up reasonably well, the economy should start to pick up a little in the second half of the year (although we are talking 8% growth rather than 12%). But I certainly don’t think the worst is behind us yet.

Other emerging markets could still thrive

But even if it is overstated, rapid Chinese loan growth shows how the next couple of years are going to be about the haves and have-nots when it comes to finance.

The Institute for International Finance estimates that net private capital flows to emerging markets will be just $165bn in 2009, down from $466bn in 2008 and $929bn in 2007. On that basis, many emerging economies are going to have to cut back sharply their investment plans over the next year or so.

But emerging economies are not all the same. Some – including much of Asia – have substantial amounts of domestic capital. Others – led by Eastern Europe – are in much more trouble.

Those that have capital can cushion the downturn somewhat through fiscal stimulus. Even more importantly, both government and the private sector can keep investing to prepare themselves for the recovery. They can also take advantage of investment opportunities in the have-nots.

China clearly has capital. We’ve seen the government stimulus plans (which are still growing), the increased bank lending and state-owned aluminium group Chinalco paying $19.5bn for a stake in cash-strapped Rio Tinto as examples. China is clearly an exception in terms of clout, but even some other economies that will be hard hit by the export slowdown and don’t have such deep pockets could still do well.

For example, Malaysia has a liquid bond market and fairly low interest rates, making it attractive for Asian borrowers. Korean banks, which were already issuing ringgit-denominated debt before the crisis hit, are said to be keen to issue more. Export-Import Bank of Korea (Kexim) recently sold notes under an ongoing MRY3bn financing program, which includes Islamic sukuk bonds as well as conventional debt.

In fact, Islamic finance could turn out to be an important source of capital. Oil cash is no longer flooding into the Middle East and sukuk issuance halved last year, but there is still a large pool of money looking for Sharia-compliant investments.

This could be helpful for Indonesia, which is not one of the capital-rich countries: liquidity in its banking system has tightened significantly over the last year. The government hopes to drum up substantial business investment during the forthcoming Islamic Economic Forum to replace declining Western investment (although its target of $5bn sounds ambitious).

India’s investment boom is under threat

Conversely, I think India’s capital problems are worse than many investors realise. Over a third of firms’ debt and equity finance came from abroad last year and this pool is likely to be a lot shallower when it comes to raising new capital. The domestic interbank market has tightened and, while credit growth is still high, it’s slowing quite rapidly, as the two charts below show.

India’s real estate and investment booms make me suspect that rising bad loans and a bigger domestic credit crunch may not be far off. The one plus is that so far foreign direct investment has been extremely strong. However, it’s uncertain whether this can be sustained given planned capex cutbacks at multinationals; for example, carmaker Renault said this week that it may cancel a factory project in Chennai.

Meanwhile, the government’s high debt and large budget deficit leaves it in no place to fill the gap. Much of India’s infrastructure investment could be delayed, which would act as a bottleneck on growth when the economy picks up.

Turning to the markets …

| Market | Close | 5-day change |

|---|---|---|

| China (CSI 300) | 2,399 | +7.2% |

| Hong Kong (Hang Seng) | 13,555 | -0.74% |

| India (Sensex) | 9,635 | +3.6% |

| Indonesia (JCI) | 1,339 | -0.9% |

| Japan (Topix) | 765 | –3.3% |

| Malaysia (KLCI) | 910 | +1.5% |

| Philippines (PSEi) | 1,920 | -1.2% |

| Singapore (Straits Times) | 1,706 | -0.6% |

| South Korea (KOSPI) | 1,192 | -1.5% |

| Taiwan (Taiex) | 4,593 | +2.7% |

| Thailand (SET) | 446 | +0.3% |

| Vietnam (VN Index) | 275 | -2.5% |

| MSCI Asia | 75 | -2.5% |

| MSCI Asia ex-Japan | 278 | -0.5% |

Asian equities mostly gained last week, despite weak economic data in many countries. India’s factory output fell 2.1% year-on-year in December, the biggest drop since 1993, while exports slid 22% year-on-year in January. Meanwhile, Malaysia’s exports dropped 15% in December.

In the currency markets, the Indonesian rupiah and the South Korean won are down 5.3% and 3.6% over the last month. Banks and companies in both countries have fairly high levels of foreign currency borrowings and greater liquidity problems in their banking systems than most Asian countries. The Indian rupee, which has been the third worst performing major currency in Asia over the last twelve months, was up 0.9%.

Signs that the credit cycle has turned are growing. Singapore’s DBS, Southeast Asia’s biggest banking group, reported a bigger-than-expected 40% drop in profits for the fourth quarter. Non-performing loans write-offs rose 48%, led by loans to smaller businesses and private banking clients.

This article is from MoneyWeek Asia, a FREE weekly email of investment ideas and news every Monday from MoneyWeek magazine, covering the world’s fastest-developing and most exciting region.

Sign up to MoneyWeek Asia here

.