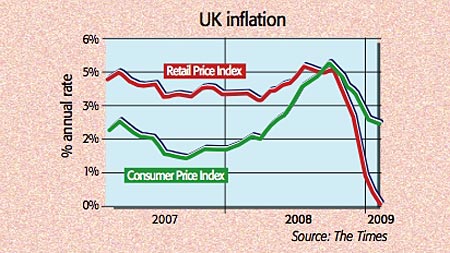

“To believe the noise, we are already in a 1930s-style deflation,” said Jeremy Warner in The Independent. But it isn’t upon us yet. Inflation is proving stickier than expected. The Retail Price Index, which includes mortgage payments, is weakening fast, falling to an annual rate of 0.1%, the lowest rate since 1960. But consumer price inflation (CPI) merely edged lower to 3%, from 3.1% the month before. And the core rate, excluding food and energy, ticked up to 1.3%. Food prices are still up 11% year-on-year, and it seems that retailers didn’t discount as heavily as usual in January, or reversed some previous price cuts, given the deep cuts in December. The cost of games, toys and furniture did not ease as expected, noted Ashley Seager in The Guardian.

Deflation is still looming…

Still, while there may be an “unexpectedly slow departure” from elevated inflation levels, the “ultimate destination” – a fall into negative territory – remains the same, said Richard McGuire of RBC Capital Markets. Lower commodity prices will drag down inflation – gas and electricity inflation is still 36% year-on-year – while the deterioration in income growth and employment will put further downward pressure on the prices of discretionary items. The slump in household wealth driven by the ongoing house-price slide is likely to wipe out all the appreciation in household assets since 2003, said Capital Economics. So indebted households will be forced to retrench sharply to repair their balance sheets. Spending could fall by 6% peak-to-trough.

That bodes ill for the consumer-led economy, which, given the recent pace of the deterioration in the data, the Confederation of British Industry now thinks will contract by 3.3% this year, said Josephine Moulds in The Daily Telegraph. There hasn’t been an annual performance that bad since the 1940s. All that spare capacity in the economy, which puts downward pressure on prices, raises the risk of “a serious bout of deflation”, said Capital Economics.

…and we could get stuck there

That in turn could lead to a “pernicious and destructive” Japanese-style slump taking hold, said Gary Duncan on Timesonline.co.uk. Retrenching consumers will defer buying because prices are falling, leading to further price cuts by businesses, rising unemployment and even more cautious consumers. A deep recession would become a “disastrous depression”. The Bank of England is now attempting to avert this with quantitative easing, but whether this will work isn’t clear. What is clear is that “the stakes could hardly be higher”.