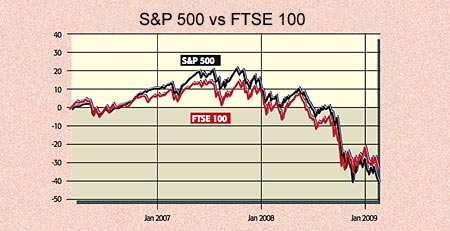

There goes another bear market rally. Major markets returned to, or fell below, their autumn lows this week. The S&P 500 lurched below November’s 12-year nadir; the Dow Jones is around its October 2002 low; the pan-European FTSE Eurofirst 300 index was at levels not seen in six years; and the FTSE 100 has flirted with its six-year low below the 4,000 level. To round off the gloomy picture, Japan’s Topix index has returned to its lowest level since 1983.

Technical analysts are primed for further heavy selling now the FTSE has breached the 4,000 mark, the lower point of its narrow trading range since January, while the S&P has fallen through its November support level. According to the Dow Theory school of technical analysis, the latest lows in the Dow Jones index and the Dow Jones Transportation Average suggest that there is no prospect of a genuine reversal soon.

But there’s quite enough fundamental data out to explain why “there’s no conviction in any sector of the marketplace”, says Gordon Charlop of Rosenblatt Securities. Banking jitters have intensified, with the crisis in eastern Europe raising fears over Western European banks’ exposure. Both Citigroup and insurer AIG look set to receive further US government help, and JP Morgan has slashed its dividend by 87%. The absence of a detailed blueprint from the government on fixing the banks, and fears that some of America’s ailing banks could end up being nationalised, wiping out shareholders, have put heavy pressure on bank stocks.

Adding to the uncertainty is the prospect of yet more bank losses amid even more “record-breaking bad data”, says Martin Hutchinson on Breakingviews. Eurozone GDP is now shrinking at a 6% annual rate, reckons JPMorgan, and the Eurozone purchasing managers’ survey is at an all-time low. There is still no sign of an upturn in US property and consumer confidence is at a record low. The Bank of Japan has given the gloomiest outlook in modern history. According to former Fed chairman Paul Volcker, the global economy appears to be deteriorating faster than in the Great Depression.

Earnings are still plunging and analysts continue to “take the knife to their numbers”, says Mike Lenhoff of Brewin Dolphin. With 90% of results in, S&P profits fell 42% year-on-year, compared to analysts’ early January forecast of a 1.2% drop, says Ben Silverman on BusinessWeek.com. Estimates for German earnings in 2009 have been cut by 12% since January. In short, it’s not clear how deep the recession will be, making it impossible for markets to discount the eventual upturn. “There don’t seem to be any clear signs” that “some of the problems have run their course”, says Mike Ryan of UBS Financial Services.

What’s more, “red lights are flashing in the credit market again”, says Richard Barley in The Wall Street Journal. The premium over official interest rates that banks are charging each other for three-month dollar loans has edged up to more than 1%, reflecting the ongoing fears in the banking system. The cost of insuring high-yield European corporate debt has hit a record. As defaults rocket, the fear is that corporate bond issuance could screech to a halt, says Barley.

Investors have been “waiting for the quick fix”, says Anthony Conroy of BNY ConvergEx. They’re now discovering there isn’t one. This isn’t a normal recession, but a globally synchronised downturn following a huge debt bubble. Banks need to be recapitalised and indebted Western consumers worldwide – including the erstwhile motor of the global economy, American households – will retrench as bursting housing bubbles have severely damaged their wealth. That implies years of sub-par growth, says hedge-fund manager Felix Zulauf on FAZ.net. Get set for “substantially lower stock prices”.