Indian elections are democracy on an epic scale. Once every five years, over half a billion people get to choose their government. From the time the first vote goes into the ballot box to the last takes four weeks. It’s by a long way the world’s biggest poll – and each time it gets larger as India’s electorate grows.

With this year’s election kicking off in mid-April, the ruling Congress coalition is doing its best to talk up India’s prospects and secure its re-election. The Indian economy will grow by 7.1% in the year to April, says the government. Next year, it should manage 6%.

Those are pretty impressive numbers in the middle of a global economic crisis. Unfortunately, they’re total fiction. After last quarter’s 5.3% year-on-year growth, there’s no chance that this year’s target will be met. Meeting next year’s is also highly unlikely. India is joining the rest of the world in a credit crunch and it will be remarkable if it can grow at half the government’s target …

Investment is vital to India’s economy

Investors often think India is a more self-contained economy than the rest of Asia. That’s not true. It’s certainly less-export dependent, though exports are a bigger part of GDP than many think. But it’s heavily dependent on the rest of the world in another way.

A big part of India’s economy is investment: it was around 39% of GDP last year, up from 25% five years ago. That’s no surprise for a country at India’s stage of development and it’s certainly not bad. In fact, it’s desperately needed given the state of the country’s infrastructure.

Much of that investment is aimed at domestic demand rather than export capacity, which sounds as if it should hold up better than investment in more export-driven countries. But the snag is that around 30% of the funding for this comes from abroad, in the form of foreign institutional investment (FII) in equities and bonds, and foreign direct investment (FDI) in setting up local business and facilities.

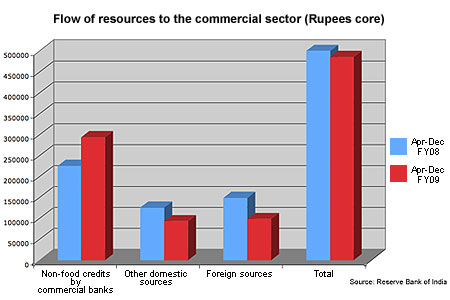

Since the global economy melted down, those investment funds have gone into reverse. Investors in Indian equities have pulled out all the money they invested since 2006. And other flows of capital are also drying up. Take a look at the chart below, which compares the sources of new capital for companies in April-December 2007 and 2008.

You can see that while the overall amount raised is down only slightly, the source is very different. Increasingly, funding is come through bank loans, with other sources of funding such as share placements and foreign borrowing down 25%-35%. Bear in mind that this covers the whole nine months, while markets only really froze in the summer, so this suggests a pretty severe drop in the last part of the year.

What’s more, if you look at the lending detail more closely, you can see that the bank credit increase is solely down to an explosion in lending by public sector banks. Private and foreign-owned banks are also pulling back.

Banks can’t fill the gap – and don’t want to

That might not sound like too big a problem – as long as Indian banks can continue to increase lending, the gap can be filled. And at first glance, that looks perfectly possible. For example, the loan-to-deposit ratio is low at 73%, suggesting that banks have plenty of scope to increase lending.

But Indian banks are obliged to hold 25% of their assets in government bonds. Once that is taken into account, their ability to lend more is clearly limited. The government could remove that cap – but that reduces the market for its own debt. With a likely budget deficit of 9-10% next year – and ratings agency Standard & Poor’s threatening to downgrade the country’s debt to below investment grade – that probably isn’t an attractive option.

What’s more, all public sector and Indian-owned banks are supposed to direct 58% of lending towards agriculture and priority sectors. So while these areas may do okay, less favoured ones – such as real estate – will be left out in the cold.

All this may be moot, because the only banks that are interested in increasing lending now are the ones that can be strong-armed into it. When the economy slows and non-performing loans rise, banks everywhere get nervous about adding more risk to their balance sheets (if only they could be so prudent in the boom times).

The latest data suggests lending growth has dropped off a cliff in the last few months, as you can see in the chart below.

FDI is holding up for now

One of the few bright points is last year’s strong pick-up in foreign direct investment, which you can see in the chart below. FDI is better than FII in equities and debt in many ways, because it’s more long-term and less able to rush out of the country at the first sign of trouble.

The October-December quarter saw a sharp 25% y-o-y fall in FDI, but January flows are reported to have rebounded 59% y-o-y. Whether this is just a rush of deals going through together or the start of a new strong trend is unclear. However, the downside risks are clearly high in this climate – especially if India gets downgraded by the ratings agencies. And even if FDI flows remain strong, to put them into context, they were only 11% of flows in April-September 2008, so they can’t fill the gap by themselves.

India is going to slow – and markets will be hit

All this means that India is likely to grow much, much more slowly than people expect this year. Back in the 2001-2002 slump, it grew by less than 4%, and while the economy has changed substantially, global conditions are far worse. Looking for a similar result this time strikes me as optimistic rather than pessimistic.

None of this undermines the long-term case for India – although an inability to invest in infrastructure now will be a bottleneck in years to come. But it makes Indian stocks look very vulnerable as this sinks in.

That’s especially true of the kind of firms that I favour as a way to play its growth. While most people get excited about India’s IT and business services industry, I think that its enormous infrastructure needs mean that firms in those sectors have to be a big part of an India portfolio (as do the kind of firms that will tap into the huge, unskilled, rural workforce as they move off the land).

But these firms such as Grasim Industries, which makes cement, will be hit hard by the credit crunch as the money to fund these projects dries up. Yet their share prices have bounced recently, as you can see below (Grasim is the white line, shown against the Sensex benchmark index in orange).

One big worry is the real estate industry – which is obviously a major customer for the construction and building materials groups – because this sector looks like it’s heading for a very hard landing. There are no full property indices for India, but many areas are said to have seen residential prices rise by 200%-plus in the 2005-2008 period.

But with credit drying up, speculators pulling out and prospective buyers losing confidence, the bottom is falling out of the market. Developers are reported to be slashing prices by 30-50% in former hotspots such as Mumbai. The commercial sector is also being hit, with capital values and rentals for office space dropping 10-20% in some cities, according to consultants CB Richard Ellis.

Given the scale of the boom, the fallout is likely to be substantial. Regulators seem worried: the Reserve Bank of India is reported to be examining the books of ten major real estate firms to check their solvency and see whether default on their loans would pose any risk to the banking system.

Update on Ezra

Time for a quick update on Ezra (SIN:5DN), the Singaporean offshore oil services play I’ve been following. The firms has cancelled orders for two vessels it had on order at a Norweigan shipyard after the yard ran into financing troubles. The group has received a full refund of its deposit. In these conditions, that’s good news. It will leave Ezra with less gearing, and if its peers also cancel a number of orders – which is likely – it will mean a tighter market for support vessels and thus higher rates when the oil cycle picks up again.

On the downside, it looks as if its 49%-owned subsidiary EOC may be struggling to get financing for a new project. The firm is understood to have won a tender to supply a floating production, storage and offloading vessel for Premier Oil’s Chim Sao project in Vietnam, although this hasn’t been confirmed. However, Premier last month was reported to be asking other firms to tender for the project as a backup in case its chosen provider was unable to raise financing.

While the loss of this contract wouldn’t be a big issue in terms of Ezra’s prospects, this situation shows how much of a drag the credit crunch will exert on the oil and gas sector. The more projects are delayed or cancelled because of an inability to get funding, the worse the production outlook will become, meaning that $30-$50/barrel range isn’t likely to last long once the global economy picks up again.

Turning to this week’s other news …

| Market | Close | 5-day change |

|---|---|---|

| China (CSI 300) | 2,380 | +7.9% |

| Hong Kong (Hang Seng) | 12,834 | +2.5% |

| India (Sensex) | 8,967 | +2.4% |

| Indonesia (JCI) | 1,361 | +2.5% |

| Japan (Topix) | 765 | +5.6% |

| Malaysia (KLCI) | 857 | +1.6% |

| Philippines (PSEi) | 1,832 | -1.2% |

| Singapore (Straits Times) | 1,597 | +1.2% |

| South Korea (KOSPI) | 1,117 | +4.0% |

| Taiwan (Taiex) | 4,962 | +1.3% |

| Thailand (SET) | 430 | +1.1% |

| Vietnam (VN Index) | 287 | +6.0% |

| MSCI Asia | 72 | +6.1% |

| MSCI Asia ex-Japan | 274 | +3.8% |

Thailand announced plans for a Bt1.4trn ($40bn) three-year stimulus plan aimed at infrastructure, education and healthcare. However, only Bt60-80bn is likely to be spent by the end of this year. In political news, six members of the cabinet survived a vote of no confidence in parliament, but the relatively low margin of approval for foreign minister Kasit Piromya suggested some divisions within the coalition government.

China’s Asia Aluminium, one of the world’s largest aluminium processing companies, has filed for provisional liquidation after a failed attempt to buy back $1.2bn of debt at heavy discounts. The firm, which makes frames used in high-rise construction, was struggling to find cash to service its debt after the construction bubble popped in markets such as Dubai.

An unnamed Chinese municipal government had offered to provide new financing to the firm in exchange for existing lenders taking a haircut of more than 70% on their bonds; however investors looked likely to reject this and the government withdrew its support. A full liquidation is likely to be a complicated test of China’s bankruptcy laws, since the case involves a large number of creditors and several jurisdictions.

And Coca Cola’s $2.4bn bid for Chinese juice maker Huiyuan was blocked by the authorities on the grounds it would hurt competition. However, many commentators argued that the decision smacked of protectionism rather than consumer protection; which still relatively small, the takeover would have been the largest purchase of a Chinese firm by a foreign business.

• This article is from MoneyWeek Asia, a FREE weekly email of investment ideas and news every Monday from MoneyWeek magazine, covering the world’s fastest-developing and most exciting region.

Sign up to MoneyWeek Asia here