For some reason, there are a lot of people out there who can’t stand the gold standard. Maybe their hostility is in reaction to the large (and growing) number of gold bugs who think the worst day in history was August 15, 1971. But since I’m an economist, not a psychoanalyst, all I can really do is patiently explain how silly the anti-gold arguments are, rather than speculate on the motives of their authors. For today’s article I will focus on a recent Bloomberg piece with the suggestive title, “Gold Standard Fans Yearn for Great Depression.”

Gold is volatile?!

Early in his essay, the Bloomberg commentator Michael Sesit gives a rapid-fire sequence of flaws with the barbarous relic:

“A return to the gold standard, where countries peg their currencies to a given quantity of the metal and thus to one another, is a bad idea. Gold-based monetary systems are overly rigid and restrictive, possess a deflationary bias and can be volatile. They make long-term inflation dependent on the pace of mining output in places such as China, South Africa and Russia.”

Let’s take these one at a time. To criticise a monetary system based on gold as “rigid” only makes sense if you believe that printing green pieces of paper makes a country richer. After all, the only rigidity enforced by the gold standard is on the central bank’s use of the printing press. Requiring the government to maintain a fixed dollar/gold exchange rate is “restrictive” in the same way that the Bill of Rights limits the discretionary power of the feds.

So yes, if Mr. Sesit thinks that the government does a good job centrally planning the economy with injections of new paper money, then I can see why he would consider the gold standard a bad idea. But let me ask you this: would you trust your next-door neighbour to use a legal-tender printing press “responsibly”? Now what about the people in DC? If we’re going to be foolish enough to give them a printing press in the first place, don’t you think it’s a good idea to put some strict rules in place?

What’s so bad about falling prices?

Sesit’s next point is that the gold standard has a “deflationary bias.” So what? That’s one of its virtues, that the purchasing power of the dollar doesn’t fall or might actually increase over time. Even mainstream macro-economists — whether neo-classical or New Keynesian — have come to realise over the last few decades that long-term predictability in monetary policy has definite advantages, and that in the long run, the best thing the monetary authorities can do is provide a currency with stable purchasing power.

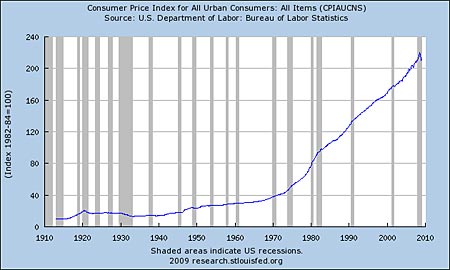

So you tell me: looking at the graph below of the Consumer Price Index, when was the value of the dollar stable and predictable, and when was it really volatile? In which environment could businesses and investors confidently make long-term decisions? Remember that FDR took away private citizens’ right to redeem dollars for gold in 1933, and then Nixon finally removed even the ability of central banks to do so in 1971.

As the chart above makes fairly clear, US prices (measured in dollars) exploded after Nixon formally closed the gold window. And what the chart above doesn’t reveal — since it only goes back to 1913 — is how stable US prices were throughout its early history, compared to the 20th century. To get a sense, consider the following chart showing the price of gold (measured in US dollars per ounce) over a long stretch of time:

Remember, Mr. Sesit is warning us that under the gold standard, things were very volatile.

Let me deal with a possible objection: the opponent of the gold standard might look at the above chart and say, “Well of course the dollar-price of gold is stable under a gold standard; that’s true by definition! The problem is that this enforced stability means that other parts of the economy get jerked around because of the arbitrary handcuffs placed on the central bank.”

But the historical record does not support this (typical) claim. I always remind people who tout the stabilising virtues of central banks that the Great Depression started fifteen years after the Federal Reserve opened its doors. Whether you subscribe to the Austrian theory (see this and this) that the Fed pumped up the stock market with artificial credit in the 1920s, or whether you subscribe to the Friedmanite theory that the Fed pushed on the brakes too hard in the late 1920s and then didn’t inflate enough in the early 1930s, either way you are blaming the Great Depression on the botched policies of the Federal Reserve.

In contrast, throughout its previous 150 or so years, the American economy had managed to do just fine without the Federal Reserve “fine tuning” the money supply. Yes, there were occasional panics (the term they used before “depression”) when the major economic powers adhered to the classical gold standard, but these business cycles paled in comparison to the Great Depression.

What about those foreign gold producers?

As for entrusting our money supply to gold miners in China, Russia, and South Africa, so what? When it comes to money, the great danger is a massive inflation. That’s the only way you can really destroy an economy: through flooding it with more and more paper money so that prices start rising at runaway rates.

One of the prime virtues of using gold as money is that the annual output is a small fraction of the total world stockpile. We never need fear that prices — if they were expressed in terms of gold ounces — would rise at Zimbabwean rates. The absolute worst that could happen is that all of the major gold producers decide to stop operations in order to punish the United States. Note that they couldn’t simply refrain from selling to American buyers: because gold is even more fungible than oil, the gold exporting countries would need to cut off all of their buyers if they wanted to punish Americans. Now how long could they afford to do that?

Unlike oil or other commodities intended for use in production, when gold is used as a money, a given amount can always “do the job.” It’s true that a sudden interruption in the growth of the world stock of mined gold would put downward pressure on prices, if those prices are quoted in gold ounces. But soon enough people would adjust, and would factor in the new trend to their expectations. There were plenty of long stretches in world history where genuine economic prosperity went hand in hand with gently falling prices. In any event, could those mischievous gold miners in Russia do anything like this to our money supply?

A Gold Standard won’t work because it will be violated

Sesit concludes with an odd argument:

“What’s more, a gold standard isn’t the panacea its advocates claim. A central bank’s ability to adhere to it is only as strong as the population’s willingness to endure the pain associated with enforcing the system.

“Countries periodically abandoned the gold standard during times of war — Britain during World War I, for example — and free-spending Latin American countries were repeatedly forced to exit the system in the late 19th century. The Bretton Woods System collapsed in 1971 when the costs associated with fighting the Vietnam War forced President Richard Nixon to suspend the convertibility of dollars into gold.

“If you don’t have faith in central bankers or politicians to ride herd over inflation, why would you trust them to keep a country on a gold standard for more than a short period of time?”

I’m not sure how to answer this. It’s true, I don’t trust central bankers to stick to a gold standard; that’s why I think the government should get out of the money industry altogether. Suppose we were starting in an initial state of pure laissez-faire in money and banking, and someone said, “Hey I know! Let’s give this Princeton professor — what was your name, sir, was it Ben? — a printing press, but be very stern that he can’t overdo it and allow the gold price to rise more than 1% from the day he starts. Does that sound like a good idea?” In response, I would obviously say, “No, that seems rather risky. I think we should stick to the current system, where the market determines how much new money is brought into the economy through gold production.”

But that’s not where we’re starting. If we’re going to have a central bank, it makes a lot of sense to put in place rigid restrictions on it. Notice you could use Sesit’s argument for any recommendation to restrain inflation. For example, Milton Friedman famously recommended that the central bank announce a fixed rate of growth in the money stock. Well gee whiz, Dr. Friedman, if you don’t trust the central bank to responsibly exercise discretionary policy, how can you trust them to stick to a fixed rate of growth?

And the same thing applies to the Bill of Rights, too. If you can’t trust the politicians to respect freedom of speech, why would they respect the First Amendment?

Gold Standard: conclusion

In closing, let me admit that a hardcore libertarian really could say that it is a waste of time to defend the gold standard, or even the Bill of Rights for that matter. Maybe they really are diversions, little gimmicks that the politicians can use to fool a gullible public into thinking they are safe.

But that is clearly not what Sesit is arguing in his Bloomberg piece. No, he is arguing that the gold standard is a bad idea because it keeps the central bankers from using all the latest, cutting-edge macro models to fine-tune the economy.

Rather than his proposal, I would far prefer the classical gold standard. It’s true that the government can always renege on its pledge to maintain a fixed peg to gold, but at least everybody would know exactly when the government cheated. You would at least avoid absurdities such as the present crisis, in which people are actually praising the Fed for pumping in unprecedented amounts of new money in order to “help.”

• This article was written by Robert P. Murphy for the Mises Institute, and was first published on 16 March 2009