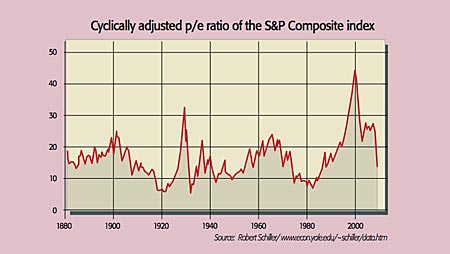

The current rally is another in the long bear market that began in 2000, says Russell Napier of CLSA. A new bull market is still out of the question; valuations did not fall low enough in March (see chart) and there was none of the “revulsion against equities” needed for a true market bottom. Nonetheless, investors should not bet on this recovery running out of steam yet. “The last rally lasted from 2002-2007 and this current one should last for a few years.”

Valuations are crucial for determining very long-term returns, but they don’t help determine turning points and rallies; investors looking at the still-high valuations after the dotcom shakeout were “wrong-footed by the rise of almost 90% in the Dow Jones Index from 2002-2007”. Instead, it is inflation and deflation swings that determine rallies, Napier argues.

History suggests that equities bottom amid deflation or fear of deflation and approach a top when inflation nears 4%. At present, we’re early in the reflation cycle and “although forecasting inflation is incredibly difficult in a period of quantitative easing (QE)”, the 4% level is unlikely to be breached until late 2010 or 2011, reckons Napier, suggesting bullish conditions for equities until then.

It may seem “absurd or at least premature” to talk about inflation yet, say Joachim Fels and Manoj Pradhan of Morgan Stanley. After all, the global economy is still in recession and headline inflation remains negative in many countries. But “markets are too sanguine”, pricing in average inflation of just less than 2% a year over the next ten years. That’s lower than the past decade, when in reality it is likely to be higher.

Globalisation, deregulation and higher productivity (from technological progress) all helped keep inflation low; these forces will be less prevalent in years ahead. Central banks have responded to the crisis with “an unprecedented amount of monetary stimulus” and this is likely to be “kept in place for too long”. While talk about withdrawing from QE has begun, “central banks will most probably not be able to withdraw monetary stimulus rapidly without putting at risk the tenuous recovery” and are likely to err on the side of ending it slowly, leading to higher inflation.

It may not be that simple, says Niels Jensen of Absolute Return Partners. “There’s no question that in a cash-based economy, printing money… is inflationary. But what actually happens when credit is destroyed at a faster rate than central banks can print? With around $14trn in credit destroyed in the US so far and around $2trn injected by the Treasury and the Federal Reserve through monetisation and fiscal stimulus, there is “a sizeable gap between the capital lost and the new capital provided”.

Banks are choosing to repair their balance sheets rather than lend out the extra liquidity supplied by central banks. Until that money is put to work, conditions will be deflationary. The experience of Japan is that “once you get caught up in a deflationary spiral, it is exceedingly hard to escape”.

In this scenario, the economy will be volatile due to “the Anglo-Saxon consumer-driven growth model having been bankrupted”, which is bad for corporate earnings. There will be no gentle inflationary tailwind for equities: markets will be choppy, making active trading “the most likely way to make money”. Long term, Napier and Jensen’s scenarios also end with valuations falling back to historic lows. Until then, we won’t be in another long-term “buy-and-hold market” for equity investors.