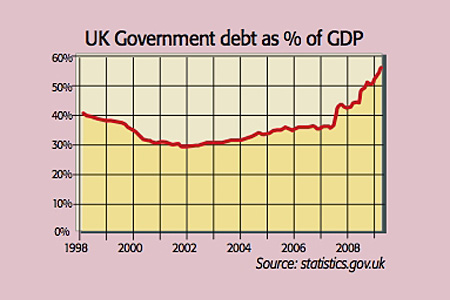

Britain is slipping ever deeper into the red. Government borrowing hit £13.5bn in June, the highest figure on record for that month. In the first three months of the fiscal year, borrowing doubled year-on-year to £41bn (£700 for every citizen) as tax revenues crumbled by 10% – faster than the Budget anticipated – and social security spending rose. Government debt is now a record £799bn – 56.6% of GDP.

What the commentators said

At this rate, borrowing is broadly on course to meet the Chancellor’s full-year target of £175bn, said Capital Economics. But with “the full hit from the recession” yet to feed through, an even bigger total of £200bn looks likely. And we can’t count on a rapid improvement over the next few years, said Gary Duncan in The Times. Think tank, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, warns that with a lacklustre recovery in the offing, by 2013-14 the deficit could still be around £120bn, a fifth higher than the government expects. And that’s only if future public spending is tightened more than currently envisaged.

With public debt “vaulting” towards 100% of GDP and no clear plan on how public finances will be brought back under control, “Britain is lucky” that foreign investors have not imposed higher interest rates on gilts, as Ambrose Evans-Pritchard pointed out in The Sunday Telegraph. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned last week that “this benefit of the doubt is not going to last forever”.

Higher long-term interest rates would raise the cost of state borrowing and interest payments and undermine growth. There could even be a “strike by gilt buyers”, followed by a sterling crisis, said Alex Brummer in the Daily Mail. When investors decided in the 1970s that they would no longer fund Britain’s deficits because fiscal policy remained too loose for too long, the IMF had to step in, added Mansoor Mohi-uddin of UBS.

The “danger signals are flashing”, said Liam Halligan in The Sunday Telegraph. Since March, when quantitative easing began, gilt yields have climbed (as prices have fallen) even although the Bank of England has snapped up almost half the gilts the government has issued.

And the vast global supply of debt hardly helps; the UK is set to borrow three times as much as Italy, and twice as much as Germany and France this year. “If Britain can escape with a gentle rise in gilt yields,” rather than a “steep and sudden” jump, said Nils Pratley in The Guardian, “we’ll be doing well”.