Which countries were most responsible for the financial crisis that engulfed the world last year? If you’ve been following the political debate over the last few months, you’d be forgiven for thinking it was a handful of secretive tax havens, such as the Cayman Islands, Jersey, Switzerland or Monaco.

Everyone from President Obama to France’s Nicolas Sarkozy to our own Gordon Brown has been queuing up to denounce the thriving offshore industry. Every G20 summit comes with a ritual denunciation of banking secrecy and a fresh pledge to force open accounts. The suggestion is made that the huge fiscal deficits now being run up around the world could be plugged by clamping down on tax lost via offshore financial centres. Bullying tactics have been adopted against small countries to force them to change their laws in ways that suit their bigger and more powerful neighbours.

The truth behind the attack on tax havens

Yet two reports published in the last week showed that just about all the accusations hurled so furiously against the tax havens are simply wrong. The UK Treasury asked the accountants Deloitte to look into how much tax is lost through offshore loopholes. The answer? Not very much, as we’ll see in a moment. Meanwhile, the left-wing Tax Justice Network, which campaigns ferociously against tax havens, has just published a report on the most secretive, least co-operative financial centres in the world. The winner? Delaware in the United States, with the City of London coming in not much further down the list.

In truth, the attacks on tax havens are led by politicians guilty of presiding over precisely the systems of secrecy they criticise elsewhere. What they are really frightened of is the way that ‘havens’ provide an alternative to their own high-tax, big-spending policies.

It is certainly hard to escape the verbal hand grenades lobbed at the tax havens by the world’s leaders. In the US, Obama has launched a fierce crackdown on American firms using offshore subsidiaries for tax planning, pledging to raise tens of billions in extra revenue to plug his budget deficit. The Swiss banks have been forced to hand over the details of thousands of account holders. The French president promised to “put the morality back into capitalism” by clamping down on the industry. The Germans have been bullying Liechtenstein into handing over details of account-holders, while Gordon Brown promised “action against regulatory and tax havens in parts of the world which have escaped the regulatory attention they need”.

But how much tax is actually lost through the havens? And how secretive are they really? As it turns out, not nearly as much as people think.

Britain’s tidy profit from tax havens

Britain has always been in an odd position vis-à-vis tax havens, because many of them – Jersey, the Isle of Man, Bermuda – are British crown dependencies. The Treasury has just published a report from Deloitte on their impact on the world financial system. The results were not quite what you might expect.

Written by Sir Michael Foot, a former director of the Bank of England, the report estimated that the amount of tax lost to the British government as a result of companies routing transactions through tax havens was less than £2bn, far less than previous estimates suggested. In a country where the budget deficit looks set to breach the £200bn barrier, that’s little more than a rounding error – less than 1% of the shortfall in government revenues. In exchange, the British banking system benefits from its relationship with the dependencies. They are used by British banks to gather funds from around the world, which are then used to bolster the banks headquartered in London. So, for example, in a single quarter this year the dependencies provided almost £200bn in net funds to British banks. If the world was really to clamp down on tax havens the way Brown promises, Britain would be a net loser. It would collect only a tiny bit more tax. Against that, it would lose even more as the British banking system became less profitable – and so paid less corporation tax.

Nor does the secrecy charge have the weight you might imagine. The Tax Justice Network’s ranking of the most secretive financial centres makes for surprising reading.

Right at the very top of the list is Delaware, the US state routinely used by American corporations as their place of incorporation because of its pro-business legislation. Britain came in at fifth place, while Belgium and Ireland also featured in the top ten. Jersey didn’t make the top ten, nor Liechtenstein. Monaco was right down at the bottom of the list, ranking as one of the most open financial centres.

Offshore centres are perfectly legitimate

So when you examine the evidence, it turns out that the tax havens are not actually costing much in the way of lost tax. And nor are they particularly secretive.

There should be nothing in that, of course, to surprise anyone who actually knows how the financial system works. In reality, the offshore centres are doing two things, both of them perfectly legitimate.

Fiscal systems around the world have become ever more complex as governments try to squeeze impossibly high amounts of tax out of the system. It’s hardly a surprise that in an increasingly globalised world, firms choose to route business through centres where taxes are simple, low and straightforward.

And they provide an alternative for people who object to paying the high rates of tax that governments in most of the developed world impose. People may or may not approve of that: but in a free world, surely it is an individual’s right to base themselves somewhere where half their income won’t be confiscated from them every year if that is what they want to do?

If politicians were really serious about cracking down on tax havens, Obama would be dealing with Delaware and Brown would be hammering the City. And they would be a lot more honest about how their own policies have helped fuel the growth of these havens.

But then it is easier to launch attacks against scapegoats. And if politicians didn’t pretend they could raise more tax by plugging loopholes, they might have to start telling people how they planned to fix their deficits.

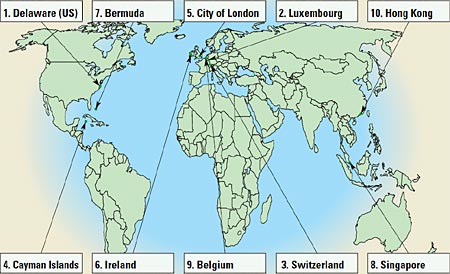

The world’s ten most secretive financial centres

The Tax Justice Network has listed the most secretive, most heavily used financial centres in the world – and as you can see below, the worst offenders are not necessarily the classic ‘tax havens’.

1. Delaware (US)

As secretive as the Caymans (see below) but hosts far more corporate activity.

2. Luxembourg

A preferred choice for the offshore rich. Has EU opt-out, like Belgium (see below).

3. Switzerland

Specialises in “traditional banking secrecy” and resistant to calls to change.

4. Cayman Islands

Attract a huge amount of corporate activity from the Americas.

5. City of London

Among the most transparent centres, but still a vital hub for offshore finance.

6. Ireland

Enjoys an “engrained culture of Victorian secrecy”, says The Economist.

7. Bermuda

Tax-sharing deals with the US and UK have helped, but secrecy is still rife.

8. Singapore

The self-styled “Asian Switzerland” is still a Mecca for offshore wealth.

9. Belgium

Still opts to withhold tax at source under EU rules to preserve banking secrecy.

10. Hong Kong

Its markets for property and shares are dominated by secretive tycoons.