It’s a bad time to be trying to make a living out of Japanese stocks. Over the last year, several outfits have shut down their brokerage businesses: Pali International has closed its doors in London, and a few weeks ago, Bloomberg reported that KBC plans to sell its loss-making Japan brokerage business too.

Still, given the events of the last 20 years, the only surprise is that there were so many Japan-focused businesses left to close. The Japanese have suffered two decades of near non-stop recession with impressive stoicism. As the rest of us indulged in a series of asset bubbles and the greatest global credit expansion ever seen, they put up with falling wages, the endless hum of needless construction work as their taxes were spent on ‘stimulus’ projects, and a persistent and deeply damaging deflation.

Yet when the global crisis came, Japan took a larger hit to GDP than anyone else. Even when the markets rebounded in March, Japan was hardly the best performer. The Nikkei 225 is 40% up on last March’s lows, but it’s still 75% or so below its 1989 high. It’s starting to look a bit pathetic.

The trouble with Japan

Japan’s problems are well known. It had a huge bubble, then a huge crash. Twenty years of deflation and deleveraging ensued as companies and individuals cleared debts. It has bad demographics – too many elderly and not enough young people – and it saves too much and spends too little. The strong yen has hit the competitiveness of Japan’s core industries hard, just as China has entered the market.

Worst of all, it has a huge public debt problem. Two decades of trying to use fiscal stimulus to banish recession has left Japan with gross debt near to 200% of GDP. That’s nasty – and given Japan’s ageing population, it could get far nastier. According to Société Générale’s Dylan Grice, in any normal environment these debt levels should already have led to hyperinflation. The Japanese have only got away with it so far because Japan’s savers have been willing to pour money into the Japanese Government Bond (JGB) market. That’s because inflation has been absent from Japan for so long that the Japanese are “unable to perceive the risk of inflation because they cannot imagine it”. So bond yields have stayed low and Japan has been mired in deflation.

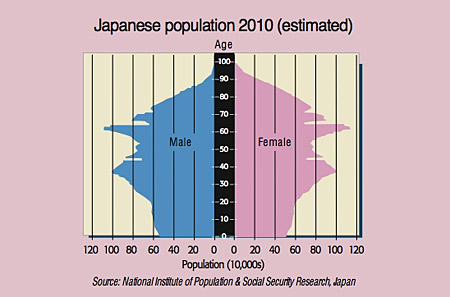

But this can’t go on, says Grice. The investors who’ve been buying bonds are now reaching retirement age (Japan has a population bulge at around 60-65). They won’t want more bonds. Instead, they’ll have to sell the ones they have. Who will replace them as buyers? Not the international capital markets. They won’t accept a yield of just 1.3%-odd from a government for which, from this year, “tax revenues will be less important than borrowing as a source of income”. In 2010, Japan is set to borrow $480bn and get in just $405bn in tax. For every yen the government takes from its citizens, it spends at least two. So at some point, says our own Bill Bonner, the Bank of Japan will have to “let the printing presses roll” and embrace “the bang of hyperinflation” – effectively defaulting on its debt by hugely eroding its real value.

How worried should we be?

We should be concerned. But not quite as worried as Bonner and Grice. Japan’s net debt (after netting off saleable state assets) is more like 100% of GDP (that’s bad, but much less bad). As Martin Currie’s John Paul Templeton puts it, it makes the problem “chronic but not acute”. And inflation and default are not the only ways to sort out the debt problem. The other time-honoured method is to make the taxpayer take the strain.

Now may not be the best time to raise taxes. But they could be better collected. Japan has what you might call a vibrant black economy. The Yakuza (Japan’s organised crime gangs) are not keen taxpayers, despite their grip over large areas of the economy. And the nation is jammed with small firms that, as Peter Tasker puts it in Newsweek, “conveniently chalk up accounting losses even when the good times are rolling”. Sales tax in Japan – the one tax even the Yakuza can’t avoid – is still only 5%.

And a little bit of inflation could raise the tax take pretty quickly. One reason it has fallen so much is that falling wages have pushed low-paid workers out of tax brackets, while falling asset prices have hit revenues from asset-related taxes too. In fact, inflation (as long as it stays single digit) may well be the answer to most of Japan’s problems. Got lots of public debt, a population that won’t spend, and a currency you want to weaken? Inflation is the solution. Right now Japan is still stuck firmly in deflation. But there are reasons to think that may change.

Last year Japan kept a tight rein on monetary policy even as the rest of the world went as loose as it could go. But there is talk that the new government may force an inflation target of, say, 2% on the Bank of Japan to try to get things moving. That would loosen monetary policy and so push down the yen. Japan, which like the rest of us has been hit by deflationary pressures from China over the last decade, may also find that changes as inflationary pressures rise there too. If the era of low inflation ends globally, Japan may find it easier than it thinks to break out of its own deflation.

Of course, if Japan is going to pull out of its slump it needs new policies. So it’s good news that after 50 years of LDP rule it has a new government, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), led by Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama. Nothing changes in Japan in a hurry and expectations are low. But there are signs that the new leaders ‘get it’: instead of indulging in pointless public works to get the economy moving, Hatoyama wants to ease the Japanese back into the shops.

The DPJ say they want to drive growth via consumption, not investment. They’ve backed this up with a generous-looking child allowance. And they seem to be looking more at the state of the nation’s small- and medium-sized firms than its international names. But the most important thing about this government is that they were elected at all. The very fact that the Japanese people voted for change after 50 years surely means they are ready for that change.

Things really aren’t that bad…

Imagine if the UK’s unemployment rate was just 5%. We’d be pleased, wouldn’t we? Not so the Japanese. Their rate peaked at 5.7% in July, then fell in four of the five following months. Most political leaders would “chew their arms off” for numbers like that, says KBC’s Jonathan Allum. But when the latest data came out, Mr Hatoyama miserably told reporters: “I don’t think we can be optimistic at all because the number is still more than 5%.” But official gloom aside, there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that Japan is pulling out of its most recent slump. Last Monday’s GDP report showed the Japanese economy growing by a faster-than-expected 1.1% during the last three months of 2009, for example.

And a second demographic trend – one that’s good for Japan – is on the way. Look at a chart of Japanese population banded by age and you’ll see two bulges. The first is of the baby-boomers, now hitting 60-odd. But the second is of people reaching their late 30s and nearing 42. That, as anyone with children knows, is the age at which people’s consumption grows most rapidly. That’s got to be good for consumption over the next few years.

Finally, a few points on the corporate sector. New Japan bull Thomas Becket of PSigma Asset Management points out that, for the last 20 years, many Japanese firms have focused on repaying debt and building up cash. But just like non-stop credit creation, credit contraction at some point becomes unsustainable. Now net corporate borrowing has moved into mildly positive territory. Surely, says Becket, there’s a chance we’ll see the restructuring we’ve waited so long for as “Japanese conglomerates shed many of their nonsensical divisions and focus on what they are good at”. Becket expects corporate earnings to rise sharply this year. Consensus opinion sees them up 30% – he suspects 50%-60%. And we shouldn’t forget that Japan also leads the way in a number of exciting industries, including top-end technology and – thanks in part to its own complete lack of natural resources – energy efficiency.

The world’s cheapest asset class

All this is encouraging. However, none of it is the key reason why we like Japan. We like it because it’s cheap. And as pretty much every study shows, over the long term the lower the price you pay, the better the return you make.

Japan, as Becket puts it, is “unloved, unfashionable, under-owned and, most importantly, relatively undervalued”. You can buy many interesting firms trading at well below their book value. The premium to book value in general is at historically low levels – the Nikkei as a whole trades at a book value of about one. This is even more interesting than it might be in other countries, for the simple reason that Japanese firms horde cash – so their book value is ‘hard’. You can argue about the value of a second-hand steel furnace. But cash is cash.

Grice has been looking for cheap Japanese firms too. His finding? Some Japanese stocks, and big ones at that, are “worth more dead than alive”, due to the fact that they are trading at discounts to their liquidation value (see the box on page 26). All this suggests that the downside is limited, and that it wouldn’t take much of an acknowledged improvement in the fundamentals for prices to jump quite sharply. Still, it clearly doesn’t matter how cheap a market is if no one is prepared to buy into it. But they might be. Recent buying patterns suggest that “individuals are finally warming to their own market”, says Allum. If they are, it isn’t before time: right now less than 7% of Japanese individuals’ wealth is in domestic equities.

Value always outs

If the last few years have reminded us of anything, it’s that in the end the market takes care of all imbalances. It was clear from the launch of the euro that the one-size-fits-all monetary policy would never work. It just took a while for the crisis that proved it to hit. It was also clear for years that the credit bubble would implode, that the global housing bubble would crash, that the dotcom bubble was indeed a bubble, that gold was too cheap in 2000, and so on.

And now it’s clear that Japan is very cheap indeed. That doesn’t mean it’ll be up 50% by the end of the year. But it does mean it should make for a very good long-term investment. That’s why it’s Bill Bonner’s ‘trade of the decade’ – not his ‘trade of the year’. Trades of the decade aren’t much use to fund managers (they have to do OK every year to hang on to their jobs), but they are exactly what the rest of us need. My MoneyWeek colleague Cris Heaton says there’s no need to buy now as there is currently no catalyst for Japanese stocks to take off. But I’m not sure we should wait for a catalyst. We know the stocks are cheap and we know that means we’ll at some point see “stunning returns”. So – when we can’t yet know what the trigger for a rise will be – why wouldn’t we buy them now?

The best ways to invest in Japan

One of the most extraordinary things about the Japanese market is quite how many funds there are still dedicated to investing in it. Trustnet.co.uk lists 66 open-ended funds and another 12 investment trusts in Britain alone.

As contrarians, we’d prefer if there were many fewer. Still, we take comfort from the fact that most have very little money in them and have performed abysmally over the last few decades. So which of these (currently) awful investments should you buy? I met with the managers of the Martin Currie Japan Fund last week and they seemed to be sensible people with a grip on how Japan actually works. They also generally agreed with the case we make here, which makes their fund worth a look (see www.martincurrie.com, or call 0845-602 5016).

Those after aggressive investing could go for the GLG Japan CoreAlpha Fund (see www.glg.co.uk or call 020-7016 7000). The fund has been given an ‘Elite’ rating by Morningstar, which means Morningstar considers it to be “significantly better than its peers in most key respects” and expects it to outperform over the long term.

But our preferred pick would be a dedicated small-cap fund. As Becket says, in the short term, returns are unpredictable. But “at some point you should make stunning returns from these undervalued and truly hated opportunities”. As ever, we’d suggest investing via an investment trust. In Britain that gives you the choice between Baillie Gifford Shin Nippon PLC (LSE: BGS), which trades on a discount of around 15%, and the JPMorgan Japanese Investment Trust (LSE: JFJ). The latter offers slightly geared exposure and – unusually for this kind of thing – a 2% dividend. It also trades at a discount of nearly 20%.

Stocks worth more dead than alive

Liquidation value is not the same as book value. Cash and debt still get to be valued at 100% of their face value (cash obviously and debt because you still have to pay it off). But in a fire sale you aren’t going to get book value for the other assets. And you probably won’t get anything for your intangibles (what value does the brand of a bankrupt company have?).

So once you factor all this in, how many stocks really trade below liquidation value (meaning that, on Dylan Grice’s terms at least, they offer not just cheapness but real value too)? Grice offers five with market caps over $1bn – packaging group Toyo Seikan Kaisha (JP: 5901), machine tools group Amada Co (JP: 6113), broadcaster TV Asahi (JP: 9409), steel producer Tokyo Steel (JP: 5423) and logistics company Seino Holdings (JP: 9076).

A stock trading below its liquidation value is clearly cheap. But it may be even cheaper than you think if the actual business isn’t a complete dud. And the businesses of the five stocks Grice mentions are not, he says, complete duds. Instead, they have been “steadily increasing shareholder wealth” in recent years. Tokyo Steel has the second-highest operating margins in its industry, for example. Given that, and given its price, “we could be looking at some real bargains”. If you’re tempted, several brokers, including Interactive Brokers (www.interactivebrokers.com) and Killik (www.killik.com), will allow you to trade individual Japanese stocks.

• This article was originally published in MoneyWeek magazine issue number 474 on 19 February 2010, and was available exclusively to magazine subscribers. To read more articles like this, ensure you don’t miss a thing, and get instant access to all our premium content, subscribe to MoneyWeek magazine now

and get your first three issues free.