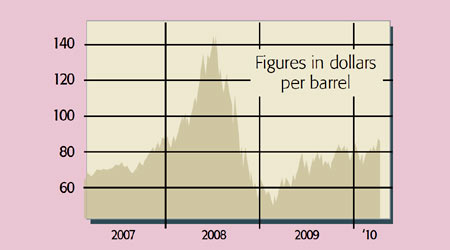

For much of the past year, oil prices have been in a trading range of $70-$80 a barrel, say Gregory Meyer and Michael Mackenzie in the FT. But over the past few weeks they have broken out on the upside. Having gained over a fifth in two months they have eclipsed $87, the highest level since September 2008. Improving economic data, notably the fact that job growth finally seems to have returned in America, has encouraged speculators to bet on further oil price increases. Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley are now pencilling in prices of $110 and $100 respectively.

But can the still-fragile global recovery, which so far has merely shown “the barest green shoots”, as Sarah Arnott puts it in The Independent, cope with even higher oil prices? The recovery of 2009 “was fuelled with oil at $62 a barrel”, not at $90 or $100, says Olivier Jakob of Petromatrix. “We fear that the latest run … will be the kiss of death for a global economy trying to avoid … a double-dip.”

How it will affect the economy

Some economists aren’t worried. The University of California’s James Hamilton says that oil’s surge to almost $150 a barrel in 2008 helped ensure that the housing-led slowdown became a recession. But this time the relatively steady rise in prices means that the “shock value” for consumers is absent. Morgan Stanley’s Hussein Allidina reckons that “economic growth would start to slow” at $100, but it won’t be derailed.

Note, however, that high oil prices were easier to shrug off in the years leading up to the credit crunch, given that growth was buoyant and consumers could easily borrow more money to temper the impact of dearer fuel. Today, the key problem is the impact of oil prices in conjunction with other headwinds facing the economy.

“Higher oil prices are adding to all sorts of other issues, such as high levels of debt, constraints on credit … and tightening fiscal policies,” says Jonathan Loynes of Capital Economics. Higher oil prices bode ill for the recovery because “they will act as a further squeeze on spending power, at a time when profit growth … and household spending power are still weak”.

British consumers are already reeling from record petrol prices, due in part to high fuel taxes, says Arnott. According to the AA, petrol sales dropped by 10% in the last quarter of 2009 and two-thirds of families are reducing their car use, more than in the “crisis-hit confusion” of late 2008.

Another way oil poses a danger is by stoking inflation, since it is used to produce a vast range of goods. Central banks could be forced to raise rates faster than they have planned. This may be a particular problem in Asia, where the “inflation genie” is already out of the bottle, says Kevin Brown in the FT. Developing economies are more oil-intensive, so the impact on inflation is greater than in the industrialised world, asYael Selfin of PricewaterhouseCoopers points out.

Can the uptick last?

All this may be academic if oil slides back over the next few months. Oil cartel Opec’s spare capacity is a historically high six million barrels. Meanwhile, Deutsche Bank notes that, at present, overall American demand for oil products is not growing. The Energy Information Administration expects it to undershoot 1999 levels. No wonder David Hunter of McKinnon and Clarke reckons that the “fundamentals will drag [oil] back down” to $70-$80.

There’s plenty of scope for a “strong correction”, says Eugen Weinberg of Commerzbank. So many speculators have piled in that bets on oil going higher have reached record levels. But given the headwinds, such as tight credit and deleveraging, “prospects for the global recovery are weak” once the global inventory bounce wears off, says Lombard Street Research. So a setback in oil could turn into a rout as investors discouraged by the growth outlook sell out in droves.