You’ve probably seen the stories about employee suicides at electronics manufacturer Hon Hai / Foxconn. You’ll also have read about how the company has doubled wages for its lowest-paid staff in an attempt to improve morale.

You may also have heard about the strikes that shut down two Honda assembly plants. Workers there were demanding pay rises to match those given at another plant which had gone on strike.

And it’s not restricted to headline-grabbing stories like these. Many people still assume that China is a big pool of low-paid labour. But things have changed in the last few years. Wages are likely to keep growing for Chinese workers.

Let’s look at why this is – and why what’s bad news for manufacturers is good news for us…

Wages are going up in China

In the last few months, employers on the Chinese coast have reported growing trouble recruiting new workers. Many migrants from the central and western provinces simply failed to return after heading home from the Chinese New Year holiday. Wages have been rising strongly in response as employers compete with each other for staff from a shrunken labour pool.

We can’t be sure this trend will stick. But it seems likely to – we were seeing signs of this happening even before the credit crunch kicked off. And if it does, it’ll mean big changes in China. Rising wages put pressure on margins at manufacturers. And as we know, Chinese manufacturers compete on their low costs. So they already have very thin margins.

Now, having to pay higher wages does not mean automatically that China’s factories will be priced out of the market. In this respect, higher wages are like the prospect of further rises in the renminbi. Many feel this threatens the export sector.

But while exporters have no pricing power individually, collectively they should be able to pass on higher costs. That’s because their main rivals are each other, not non-Chinese suppliers. They should also be able to continue cutting costs through greater efficiency.

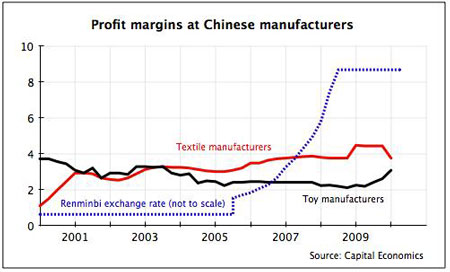

Generally, even low-end firms should be able to survive. After all, they coped with a 20% rise in the renminbi between 2005 and 2008. Margins were equally thin back then, but remained stable, despite speculation that the stronger renminbi would put companies out of business (see chart below). So part of the result will be that we in the West pay slightly higher prices for imports from China.

That said, a tighter labour market is likely to accelerate the trend for some of the lowest-paid work to leave the coastal provinces. Some of this will migrate out of China. It will end up in countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia and India, where manufacturing wages are still much lower.

Meanwhile, some will migrate inland towards the poorer central and western provinces. Here pay is lower than at the coast, although probably rising more quickly. Also, migrant workers are closer to the rural areas they originally come from. Thus the labour supply might become more dependable.

There are already signs of this in areas such as Chongqing. That’s the smoggy, grimy megacity that’s sometimes compared to Chicago for its potential as the gateway to China’s west (see map below).

Even technology firms such as Foxconn, HP and Quanta, which were previously based mostly on the coast, are now investing in manufacturing plants in the surrounding municipality.

This is all very much part of the Chinese government’s goals. The ‘Go West’ or ‘Western Development’ policy (‘xibu dakaifa’) aims to encourage the development of the poorer parts of the country. In turn, this should spread the proceeds of growth around more equally. That’s seen as important for social stability.

As an aside, ‘xibu dakaifa’ is also the driving force behind infrastructure projects such as the cross-country high-speed rail network. Many westerners look at this and argue that demand can’t justify this sort of thing.

But the point is not to earn a high rate of return now. It’s to spur growth by connecting the poorer parts of China to the richer ones. A good comparison is the canal and railway construction booms in Industrial Revolution Britain. These produced lousy returns for direct investors, but delivered huge benefits for the overall economy.

Standards must go up on the coast

What about the manufacturers who remain in Guangdong and the other coastal provinces? Higher labour costs will push them to move up the value chain. That’s exactly what China needs and is already steadily doing.

If you look at measures such as the number of patents filed (see below), you can see that Chinese research and development is on the move. (I’m not sure whether this lumps Taiwanese patents in with Chinese ones. But it shouldn’t make much difference. Taiwanese firms have so many of their factories in China now that Taiwanese R&D will flow through to more high-end manufacturing on the mainland in any case.)

By all accounts, most of the mainland patents being filed are still relatively low-level. They represent small improvements rather than groundbreaking research. But it’s a start. It’s how Asia’s other successful industrial economies started. And the need to add more value to compensate for higher labour costs will drive this process further.

This shift to higher-value industry should have one side benefit. As heavier industry shifts away from the coast to be replaced by higher-tech manufacturing, the environment should begin to improve. Pollution should fall, both in the provinces and in Hong Kong and Macau, which too frequently lie under a slate-grey blanket of smog that drifts down the Pearl River Delta.

Higher wages are good for the economy

Finally, higher wages will lead China to the Henry Ford solution. Forgive me if you’ve heard the story already. In short, Ford decided that it was good business sense to raise pay for the workers in his car manufacturing plants.

Other industrialists were horrified. But Ford realised that this gave workers more power to buy goods – including the cars they made. And this was better for the economy and his business in the long run.

This is exactly the process that China needs. It’s well-known that its economy has an exceptionally high level of investment and a low level of consumption. It’s less well-known that this isn’t because consumption has been weak; in fact, it’s grown at a healthy rate of around 8% a year.

Instead, excess profits from the export boom have been ploughed back into more investment rather than being fully shared with workers (see chart below). In other words, profits have gone towards building more capacity, rather than increasing wages.

But with labour shortages growing, firms will now need to pass a greater share of the gains onto their workforce. China may have reached what developments economists call ‘the Lewis turning point’. At this stage of development, the glut of surplus labour from the countryside tails off. As a result, wages begin to rise rapidly.

That would be painful for manufacturers. But it’s good news in the long run if parts of China have advanced this far. Higher wages and more spending power will help the Chinese economy to rebalance and drive the emerging market consumer story over the next few decades.

China is not overheating

In the shorter term, do rising wages signal that China’s economy is overheating? Some are certainly worrying about this. However, I’m not convinced. If anything, I’m inclined to think that a bigger-than-expected slowdown is possible.

First quarter year-on-year growth may have looked impressive at 11.9%. But the trend may well be turning. Many key indicators now seem to be levelling out, as the chart below shows.

In particular, the brakes seem to be going on in the property market. Policymakers recently introduced new measures to cool activity in major cities, where prices had risen sharply and bubbles seemed to be emerging. Sales were down 15.8% month-on-month on the official index. Meanwhile data from real estate consultancy CRIC suggests a 60-70% fall in new homes sales in the tier 1 cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen).

Most developers have a few months of cash in reserve. So they’re not yet slashing prices to get sales moving again. But if the government keeps restrictions tight, they’re likely to begin cracking over the next few months. Prices could fall sharply.

With real estate activity slowing and the boost from last year’s investment surge steadying, it’s quite likely that China’s growth could slow noticeably in the year or so ahead. It’s not set to crash. Investment projects that have already begun remain to be completed, and government-pushed investment in mass-market housing should be strong.

Consumption should be solid even if some of the subsidies that powered car and white good sales in rural areas are being cut. And export demand seems to be growing, judging by May’s 50% year-on-year rise, though given problems elsewhere in the world, it’s uncertain how well that will be sustained. But a much steadier pace of growth seems likely, perhaps with some fallout from bad loans made during the lending surge of the last 18 months.

China isn’t going to move from high investment to steady consumption, low-cost to high-value, cheap labour to skilled workers overnight. But it needs to continue down that path. Those of us who are looking for the long-term investment story rather than shorter-term trades on steel demand, cement output and property sales should welcome these changes – even if there’s a chance that they could cut profits and rattle markets in the shorter term.