My inbox is swelling with emails from concerned readers telling me that hyperinflation is coming soon. They talk of food prices, Chinese wages, and another round of quantitative easing (QE); some have even mentioned Zimbabwe! They tell me I’ve got it all wrong and that my deflation talk is simply bonkers.

But as informed as many of these arguments are, they are missing one thing: there’s already more than enough money in the system to create hyperinflation. In fact, it could have happened at any point in the last 39 years. But it hasn’t; and today I’d like to explain why that is.

I’d like to show you why QE hasn’t really had any effect on the ‘real economy’, and why you shouldn’t worry that the much headlined ‘QE II’ will bring hyperinflation.

QE is savings, not cash.

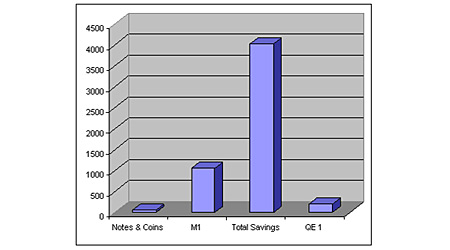

Money isn’t just for spending, it’s for saving too. And it’s important to make the distinction. The amount of cash floating around our economy is actually pretty insignificant. Take a look at the first column on the left-hand side of the chart below:

UK savings relative to cash

Data: Lloyds Bank & Bank of England

Even if you add in cash held in bank accounts ready to spend (M1, the next column), it’s still small relative to our total savings (Lloyds Bank: 2009).

To get inflation (let alone hyperinflation), you need to increase the amount of cash available to the man on the street (M1). But when the Bank of England ‘created’ money using QE, that money didn’t become ‘available cash’ for the man on the street.

So where did the money go? Nowhere. It stayed within the nation’s savings and, so long as savings aren’t for spending, that’s where it’ll stay.

Your FREE oil report: The 3 best ways to play the coming oil supply crunch right now!

- Discover how to profit from oil without ever owning a single barrel

- Why NOW is the best time to put a few carefully selected oil investments into your portfolio

All that QE did was help push up bonds and in turn the stock market too. And after the mauling of the 2008/09, savers were relieved for this little bit of respite. QE cash didn’t make its way onto the streets, and neither will the cash from QE II.

If you want to talk about serious inflation, then QE isn’t enough. For inflation to go hyper, something really desperate has to happen.

We could have had hyperinflation at any point since 1971

Imagine if we all went to our stockbrokers, banks and building societies and demanded to cash-in our savings tomorrow. That’s what happened in Weimar Germany, and it wasn’t pretty. There were people carrying piles of cash down the street in wheelbarrows, cities issuing their own money, and five-ton trucks dumping mountains of cash outside factories every morning for desperate workers to gather their pay.

How could this happen? Only if savers lose faith in the financial system and decide to move their savings to cash so they can buy hard assets.

I’m happy to concede that faith in the financial system is a little bit less than it was a few years ago. I’m also happy to accept that this faith won’t last forever. But I can’t accept that we’re close to what’s needed to make people abandon savings completely. Despite everything that’s happened, we’d still rather hold bank deposits and shares than cash and gold under the mattress.

Gold may continue to rise – and I’ll continue to trade the great yella’ bull market – but ultimately, people still feel that their savings are safe. In fact, in nearly every decade since we left the gold standard in 1971, our economy has had more than enough money (tied up in savings) to create hyperinflation. And yet it’s never happened.

Piddling amounts of QE won’t make any difference until the day comes when savers shift their wealth into cash. They won’t do that until all faith is lost – and we ain’t there yet.

• This article was written for the free investment email The Right Side.

Sign up to The Right Side here

.

Your capital is at risk when you invest in shares – you can lose some or all of your money, so never risk more than you can afford to lose. Always seek personal advice if you are unsure about the suitability of any investment. Past performance and forecasts are not reliable indicators of future results. Commissions, fees and other charges can reduce returns from investments. Profits from share dealing are a form of income and subject to taxation. Tax treatment depends on individual circumstances and may be subject to change in the future. Please note that there will be no follow up to recommendations in The Right Side.

Managing Editor: Theo Casey. The Right Side is issued by MoneyWeek Ltd. MoneyWeek Ltd is authorised and regulated by the Financial Services Authority. FSA No 509798.

https://www.fsa.gov.uk/register/home.do