Just five years after the financial crisis, are central banks laying the foundations for the next one? For some time now analysts have been pointing to signs of irrational exuberance in various asset markets. And last week, US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke said he was looking out for signs of “excessive risk-taking”.

As he didn’t appear to notice America’s housing and credit bubble in the run up to the last crisis, let’s hope his powers of observation have improved in the past few years.

Easy money boosts markets

The world’s central banks are easing on an unprecedented scale. Interest rates across the world are at historic lows and both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan are printing money with abandon. Yet “global monetary policy is going wrong”, says Ian Campbell on Breakingviews. The liquidity tide has certainly lifted markets everywhere, but it hasn’t sparked a growth revival.

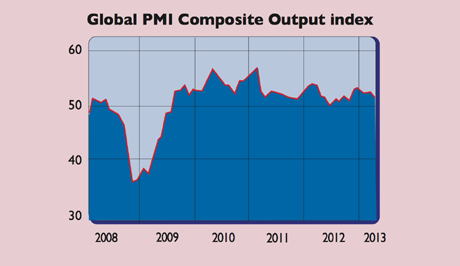

Global growth has bounced back since the crisis, but is still pretty tepid, and can hardly be described as self-sustaining. Output continues to shrink in the eurozone, China has slowed, and America, the relative star of the show, is only chugging along at an annual pace of around 2%. The above chart of the Markit/JP Morgan PMI Global Composite, an index tracking both services and manufacturing, shows how slow the recovery has been.

One reason the printed money may not have penetrated the economy, as Campbell points out, could be commodity inflation. Loose money has helped prop up raw-materials markets in recent years. US households spent 4% of pre-tax income on petrol last year, the most in 30 years.

British consumers have been squeezed by high energy prices, which have undermined consumption, a crucial pillar of growth. Then there are Europe’s broken banks. US banks have been forced to face up to their bad loans and write them off, so they have more scope for new lending than in Europe.

Past the worst

Stock markets have jumped because many economies “are well past the worst”, says Allister Heath in City AM. Equities are not yet expensive. But given the economic backdrop, and uninspiring revenue and profit reports, it’s clear that “cheap money is also doing the trick”. Yet the gulf between the fundamentals and asset prices is starkest in the credit markets.

Government-bond yields have hit record lows as prices have risen. Dodgy European credits are in demand: Portugal has just managed to sell its first ten-year bond since its bail-out in 2011, says Richard Barley in The Wall Street Journal. The European junk-bond market has seen bumper issuance even as yields have fallen to record lows. But the “underlying economic fundamentals look as poor as ever”.

Meanwhile, the yield on the Barclays Corporate High-Yield index has fallen below 5% for the first time. Covenant-lite bond issuance – borrowing by companies on highly favourable terms – is close to the 2007 peak. The bottom line, says Barley, is that “investors are being forced by extraordinarily loose global monetary policy [and the accompanying rock-bottom interest rates] to take ever greater risks to earn returns”.

What next?

So “much of the central-bank-induced madness that led to the last two bubbles is reaching ever more dangerous proportions”, says Heath. But the bubbles being blown up seem unlikely to meet a pin in the near future.

Any downturn will be greeted by more liquidity from central banks, while the global economy does not look strong enough yet for interest rates to rise and bring the loose-money party to a halt. Yet the “more markets rise on the liquidity glut, the larger the potential future asset-price falls”, says Campbell.

All this leaves us with the uncomfortable feeling that there will eventually be another sharp slide in asset markets – but given the tepid macroeconomic backdrop, not much of a boom before the bust.