Latin America is banding together to improve trade, and business is booming. British investors should grab a slice of the action, says James McKeigue. Here, he tips the best shares to buy now.

Emerging markets are in meltdown. Investors pulled $20bn out of emerging-market equity funds in June, a record. It was the same for the bond market: emerging-market debt funds lost almost $6bn in the last week of June – another record. The MSCI Emerging Markets stock index is down 13% since mid-May.

The sudden dose of risk-aversion is partly due to the US Federal Reserve’s hint that it will taper quantitative easing (QE). QE has helped suppress yields on US corporate and government bonds, driving investors to reach for yield in more exotic locations – with some worrying results. For example, South America’s poorest economy, Bolivia – which has a history of expropriating Western firms – was recently able to borrow at just 4.9%, even though it had been nearly 100 years since it issued a government bond. But now, with the Fed hinting at tighter monetary policy, risk appetite has dived.

Then there’s China. Over the last decade or so, emerging markets have made good money selling commodities at high prices. But now that growth is slowing in the world’s biggest commodity consumer, these export earnings are falling.

For regular readers none of this should be a surprise. MoneyWeek has long warned that both Chinese commodity demand and US money printing would have to end one day. But that doesn’t mean you should write off all emerging markets. In particular, some Latin American economies now offer great opportunities.

Enter the Pacific Alliance

The Pacific Alliance is a trade bloc that officially came into being last June. It combines the medium-sized economies of South America’s Pacific coast – Chile, Peru and Colombia (the ‘Andean Three’) – with their giant neighbour in the north, Mexico. Central American minnows Panama and Costa Rica also look likely to join in the future.

At first glance, the Alliance nations may seem an odd choice. Its members are exactly the sorts of commodity-rich players that look vulnerable to the Fed’s actions, and to the slowdown in China. But for certain sectors and companies at least, the sell-off is hardly the worst thing that could happen. More to the point, all of the Alliance members have used the good times to get into great macroeconomic shape, with the ‘Andean Three’ the fittest of all.

Take Peru. The country’s debt-to-GDP ratio has fallen from 47% in 2003 to 18.3%. So if growth starts to flag – last year GDP grew by 6.12% – the government can compensate by spending money on vital infrastructure, or on education and health services. Colombia, meanwhile, has cut its debt-to-GDP ratio from 55% in 2004 to 40% at present. As for Chile its government debt-to-GDP ratio is 12%, although if you include its $15bn ‘rainy day’ fund, built on the back of record copper prices, it is actually a net creditor to the world.

The Alliance countries also have of scope for monetary stimulus. Central banks in all four countries have much tighter policies than their peers elsewhere in the emerging, or indeed developed, world. With inflation under control and interest rates reasonably high, central banks can afford to loosen up if need be.

Mexico’s debt-to-GDP ratio is 35% and it is also the nation that will be least hard-hit by the commodity slowdown. Despite having large mining and hydrocarbon sectors, Mexico’s main source of export earnings is manufacturing. It is the only major Latin American economy that gets more than half of its export earnings from manufacturing. It also has world-leading automotive and aerospace industries.

The benefits

So how does the Pacific Alliance help matters? The main idea behind the Alliance is to create investment opportunities that attract money from abroad. One man who knows all about encouraging international capital to the region is Matías Mori, executive vice-president of Chile’s Foreign Investment Committee.

“When it comes to attracting large investments there is a lot of demand… The Japanese and the Chinese want billion-dollar projects and now we can offer them that by working with our Pacific Alliance partners… investors often only think of Latin America as Brazil or Argentina… the Pacific Alliance is a way of focusing attention on other opportunities in the region.” Clearly, it’s too early to be sure of whether or not it’s working. But when Peru’s former president, Alan Garcia, first mooted the idea of the Alliance in 2011, foreign direct investment in its members was $59bn. This year it should hit $73bn. Fears of a commodity slowdown may hit some projects, but the ‘Alliance effect’ should help compensate.

Another goal is to improve integration between companies from different countries. This was already happening before any treaties were signed, but the Alliance should help to speed the process. In the last year, visa requirements for member citizens have been reduced, and import tariffs cut. At the most recent summit in Cali, Colombia, leaders pledged to eliminate tariffs on 90% of members’ merchandise trade. To help develop local capital markets, stock markets from Peru, Chile and Colombia have merged to form Mercado Integrado Latinoamericano. This provides a platform for firms from each nation to trade on the same exchange, and so tap capital from a wider range of investors. Mexico is expected to join later this year.

Promoting the free movement of goods and people is a good idea, but it’s not the only goal of the Alliance. By slashing these internal barriers, politicians want to encourage regional supply chains and help local firms become more efficient producers. In that sense it’s an export union, with firms grouping together to sell goods to the rest of the world. One thing politicians are very aware of is the need to improve productivity. As Colombia’s president, Juan Manuel Santos, noted at the latest Pacific Alliance summit in May: “Maintaining our growth depends on us moving away from just selling commodities and working to improve our productivity.”

The Pacific Alliance economies are already among the most open in Latin America and the world, with a raft of free-trade deals. This helps to foster competition. But there is much more work to do. Corruption and poor governance is a big issue, especially in Colombia and Mexico, while the latter has several cosy oligopolies that reduce the efficiency of the economy. Yet there is cause for optimism, says Yves Hayaux-Du-Tilly, of London-based Mexican law firm Nader, Hayaux & Goebel.

“Mexico’s new president, Enrique Peña Nieto, has managed to agree a package of reforms with the other main parties. So far this ‘Pact for Mexico’ has delivered important changes to the education and telecommunications sectors. Now the big hope is for energy reform that could allow private firms to participate more in the oil and gas industry.”

Latin America’s building boom

One big efficiency boost will come from better infrastructure. Ever since the days of the military rulers of the 1970s and 1980s, who were generally fond of prestige projects, the region has underspent on power lines, railways, roads and airports. “Public investment in infrastructure fell from above 3% of GDP in 1988 to 1.6% in 1998,” says Irene Mia of the Economist Intelligence Unit. But while spending was falling, populations and economies were growing, straining infrastructure. “Latin America needs to invest between 2.5% and 6% of GDP to upgrade and extend the regional infrastructure,” says Mia.

Pacific Alliance governments are doing just that. Peru and Colombia are each spending about $20bn of public money – which is expected to be accompanied by tens of billions in private funding – on updating railways, roads and airports. When completed, these will have a huge impact. Unlike Britain’s controversial High Speed 2 rail project, which will shave minutes off the journey from London to Manchester, these works will make a big difference by traversing the Andes, or linking remote jungle settlements to ports.

Better infrastructure will cut costs for firms. Natural resources firms will benefit from improved links to the remote hinterland, where resources are often found, and frombetter ports, which allow them to export their produce. Consumer firms will benefit as better transport links bring brands and shops closer to rural consumers. So far there’s no shortage of interested investors.

As Luis Andrade, of Colombia’s National Infrastructure Agency, told me: “There’s been a lot of demand from local and international investors. They realise these projects can earn a steady income”. Better infrastructure will also boost integration, making it easier for companies in different countries to work together.

The rise of the multilatinas

In the last ten years, we have started to see the rise of Latin American regional companies, known as ‘multilatinas’. In 1999, less than half of the biggest 500 firms in Latin America were local. Now more than 75% are. The trend is accelerating. In the last year, a host of Western firms have sold up their Latin American businesses to local rivals.

Why? One factor is that European firms are losing money at home. As a result, some are using their Latin American operations as cash machines, taking money out of the region to shore up struggling European units. But this leaves them less able to compete with their resurgent Latin American competition. So they either lose market share gradually or cut their losses and sell up.

For British-based investors who want to invest in Latin America, the development of these large, local firms is essential. That’s because investing in local exchanges is nigh-on impossible for a small private investor. But plenty of multilatinas are now listing in America, Canada or Europe, making them accessible. Moreover, many operate in financial services, retail and leisure, allowing investors to avoid the traditional “Latin American commodity story”.

Indeed, for some of these firms a commodity slowdown won’t be a bad thing. For starters, it is likely to weaken local currencies against the US dollar. That will boost export competitiveness. Moreover, China’s slowdown is part of a rebalancing process. China’s current model of investing heavily in labour-intensive export industries is struggling. Its leaders hope to replace this with increased local consumption and higher-value manufacturing.

That should relieve pressure on Latin American manufacturers who have been hurt by Chinese competition. Michael Henderson at Capital Economics believes that “as Chinese manufacturers have begun to edge up the value chain, their dominance in sectors such as textiles has started to slip”. That creates opportunities for Latin American manufacturers.

The five stocks to buy now

We first wrote about the Pacific Alliance at the end of August 2012. Since then our tips have done reasonably well. Ternium (NYSE: TX), a steelmaker with a heavy presence in Colombia and Mexico, is up 15%. Credicorp (NYSE: BAP), a Peruvian bank that is spreading into Colombia and Chile, is up 8%. And Vina Concha y Toro (NYSE: VCO), a Chilean wine maker that was our hedge against a commodity collapse, is up around 1%. We’d keep holding all three.

Usually we like to play broad themes with cheap investment trusts or exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Unfortunately, there aren’t any that look suitable. The “‘Andean Three’ country ETFs are dominated by a few large commodity stocks. As for Mexico, its main market, and so any ETF, is dominated by the very consumer oligopolies that will be hit by Peña Nieto’s reforms. An alternative way to get broad exposure is to buy a bank. This should give you leveraged exposure to every part of the economy – acting more like an ETF should than those currently on offer.

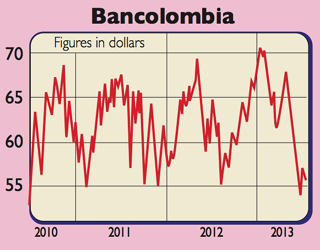

So as well as Credicorp, we like Bancolombia (NYSE: CIB). This Colombian bank’s share price has tanked in recent months, with investors concerned about how Colombia will fare in the commodity sell-off, and the state of the bank’s loans. Yet the Colombian government’s infrastructure drive should compensate for any loss of commodity business. Colombia’s banking penetration remains low and has room to grow. As JP Morgan’s Saul Martinez points out, Colombia’s “consumer credit to GDP (excluding mortgages) ratio is just 10%, versus 16% in Brazil and 11% in Chile”. Moreover, recent data suggest the proportion of loans turning bad has bottomed out.

In the longer term, Colombian policymakers are keen to develop the nation’s financial services. The head of Colombia’s Stock Exchange, Juan Pablo Cordoba, recently told me that he is working hard to grow both local and international participation in Colombia’s stock exchange, by encouraging the creation of new investment vehicles to attract capital. Meanwhile, finance minister Mauricio Cardenas wants to turn the country into a regional financial hub. All of this is good news for the country’s banks. That leaves Bancolombia looking decent value on a forward price/earnings (p/e) ratio of 12.

Another of our favourites is Mexichem (OTC: MXCHF), a Mexican chemical conglomerate. The group mines salt and fluorite, then turns these raw materials into various chemicals and plastics to sell to industry. The business is split into three divisions. One uses salt to make chlorine and vinyl, which is then turned into products including soap, shampoo, detergent, and customised PVC – the third most commonly used plastic in the world. A second unit uses the firm’s fluorite mine, which is one of the world’s largest, to churn out calcium fluoride (a mineral used to make steel, cement and glass), industrial acids, and refrigerants. Lastly, the ‘integral solutions’ unit makes finished PVC pipes and offers custom materials and engineering for agricultural projects. In short, it is exposed almost every type of industrial activity.

Around 40% of sales come from Mexico, with another 40% from the rest of Latin America. So Mexichem is well placed to benefit from the infrastructure boom being unleashed as the ‘Andean Three’ compensate for falling commodity prices, and from Mexico’s manufacturing boom. The share price has tanked recently, down 20% since April. As a result the firm, which for the last five years has traded on an average p/e of 32, now looks relatively cheap on a p/e of 18.

A final boost could come from energy reform in Mexico. Mexichem already has a joint venture with Pemex – if private companies are allowed more involvement in the sector it would create a host of new customers for the firm. Do note that the stock is traded ‘over the counter’ in America, so you’ll need to use a broker who can trade in these stocks.