Its glory days may be behind it, but Microsoft still makes solid profits, says Phil Oakley.

Microsoft is one of the greatest corporate success stories of all time. Having begun life in 1975, its Windows operating system revolutionised the personal computer (PC) market in the 1980s and established itself in millions of households across the world. Meanwhile, products such as Microsoft Office made workers far more productive. By the end of the 1990s technology boom, Microsoft had become the world’s most valuable company, and in the early 2000s, it even came under attack for being too dominant.

But in recent years, the company has been shrouded in doom and gloom. It has been eclipsed by the likes of Apple and Google, which have become the kings of the internet, smartphones and tablet computers. Microsoft has made little progress in these areas and seems to have lost its way. It has been lumped together with former champions such as Intel and Yahoo, which are struggling to cope with the shift from the PC and the growing trend of internet usage for everyday tasks.

Last week, Steve Ballmer, Microsoft’s chief executive for the last 13 years, announced he was retiring. In some ways, Ballmer has been unlucky. He took over from Bill Gates when Microsoft was at its peak and the shares of technology companies were grossly overvalued. It’s difficult to see how anyone could have made the company more valuable.

But in other ways Ballmer has to take the blame for Microsoft’s stagnation. He greatly underestimated the threats posed by Apple and Google and confused investors by trying to buy Yahoo, for example, and spending lots of money buying internet telecoms company Skype.

The shares leapt 9% on the news of his resignation. But is turning Microsoft around just a simple matter of changing the man at the top? Or is it destined for years of decline?

What lies ahead

It’s certainly very easy to write off Microsoft. Consumers are using PCs – and therefore Windows – less, and Microsoft’s share of the tablet and smartphone market is very small. Its Bing search engine cannot make money out of the internet, and while the Xbox is a very good games console, its profits don’t make much of a difference to Microsoft as a whole.

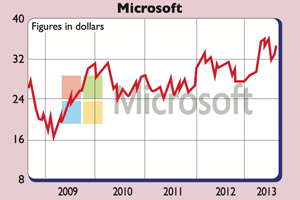

But I can’t help thinking that the media and the investment world are too obsessed with these weaknesses. Despite the seemingly constant debate over its future, owning Microsoft hasn’t been too disastrous over the last year. The shares are up by nearly 12%. That’s lower than the 17% gain of the S&P 500, but it compares favourably with Apple, whose shares have lost around 25%.

And while Microsoft’s profits have been flat over the same period, its business is nowhere near imploding. Windows aside, Microsoft actually makes most of its money from selling stuff to companies rather than retail customers. Here, the business is actually doing quite well.

Microsoft’s servers business – systems that help computer networks work – is doing well and profits are growing. The business division, meanwhile, which includes products such as Microsoft Office, is more than holding its own and could hold the key to any Microsoft revival.

The company has invested heavily in cloud computing with its Windows Azure and Office 365 products, and this could pay off. Cloud computing is growing in importance to businesses as it allows employees to access their work wherever they have an internet connection. Despite attempts by Google to gain a foothold in the office software market, MS Word, Excel and Powerpoint are deeply entrenched within most big companies. Employees know how to use them, which makes companies unlikely to ditch them for something else.

The combination of the cloud and Office means Microsoft may still have a formidable business with a big economic moat that rivals cannot breach. If demand for these services can keep growing, then there could be a decent investment case. And there’s no denying the fact that its financial performance remains impressive.

Three numbers stand out: operating margins at 34.4% are not far off Apple’s, even though Microsoft’s profits may prove more resilient than those coming from the iPhone. Free cash flow of $24.6bn in the year to June 2013 was above its reported net profits – not many companies can boast that. Finally, it has a net cash pile of $61.4bn, which means that Microsoft’s return on the net money invested in its business is a staggering 86.3%.

Should you buy the shares?

That just leaves the price of its shares. At just over $34 they trade on 12.4 times next year’s forecast earnings. A dividend yield of 2.8%, covered three times by cash flow, is not too shabby either. And Microsoft’s cash pile makes it look more expensive than it really is. Cash is obviously reflected in the share price but it contributes virtually nothing in return. Stripping this out gives the shares a free cash flow yield of nearly 11%.

Ballmer’s replacement will have a tough job – but will have some good businesses to work with too. We tipped the shares as a buy at $28 just over two years ago because we thought they were cheap. They are still cheap enough to buy now.

Verdict: buy

Microsoft (Nasdaq: MSFT)

Share price: $34.15

Market cap: $284.5bn

Net assets (June 2013): $78.9bn

Net cash (June 2013): $61.4bn

P/e (current year estimate): 12.4 times

Yield (prospective): 2.8%

Dividend cover: 2.8 times

What the analysts say

Buy: 14

Hold: 24

Sell: 2

Target price: $35

Directors’ shareholdings

S Ballmer (CEO): 333,252,990

W Gates (chair): 397,988,029

B Turner (COO): 1,050,487

• Stay up to date with MoneyWeek: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Google+