Driverless cars, super-fast trains, and supersonic planes – all look good bets for smart investors, says Matthew Partridge.

Unlike most forms of technology, our experience of transport has arguably deteriorated in the last 15 years. Roads are more congested, trains more crowded, and tighter security has made travelling by air more stressful and time-consuming. The good news is that the next 15 years should be very different. Cars, trains and planes are all undergoing major changes that should get us from A to B in comfort far more quickly and safely than today.

The future is driverless

Cars form the backbone of virtually all transport systems, accounting for over 75% of passenger miles travelled in America and Britain. Now, the promise of cars that can drive themselves is moving from science fiction to reality.

We last covered the subject in October 2012. Even in that short space of time, the pace of innovation has picked up substantially, with a surge in interest from both big manufacturers and governments.

The number of car companies making moves into self-driving just keeps growing. The head of Daimler (which makes Mercedes) made a dramatic entrance to the Frankfurt Motor Show in a driverless prototype.

General Motors and Toyota have recently given updates on how their own research is going. And Nissan has made a formal commitment to sell an affordable self-driving model by 2020, five years before BMW’s target. Industry experts believe this surge in interest will force other car makers to follow suit.

But even before the first fully autonomous cars become available to the general public, the role of the human driver will have shrunk substantially.

Driving aids that help with everything from parking to steering in light traffic are already starting to become standard on the more expensive versions of the latest models.

Meanwhile, Elon Musk, the maverick head of electric car company Tesla Motors, has stated that he aims to start selling a model that is 90% automated. (You can also learn more about his ‘Hyperloop’ plans below.)

Then there is the intriguing possibility of developing systems that can be retrofitted to today’s cars.

Earlier this year, researchers at Oxford University developed a system that can enable a car quickly to map and keep track of its surroundings. This allows it to memorise, identify, then automatically replicate certain regular journeys, such as trips to the supermarket.

Trials of this system (which is unobtrusive and can be easily installed) have been so successful that the British government has allowed it to be tested further on public roads, rather than specially modified tracks.

While it currently costs £5,000, the team hope that mass production could bring the price down to as little as £100.

Governments are starting to realise that automation could have wider social benefits. A recent report by the Department of Transport noted that automated systems have the potential to cut the number of accidents (British roads are relatively safe by global standards, but there were still nearly 200,000 injuries and 1,754 deaths on our roads last year).

Also, because these systems allow cars to travel closer to each other, they also have the potential to smooth the flow of traffic. This could help cut congestion, which is estimated to cost the British economy at least £7bn a year, and possibly as much as £30bn according to some reports.

Compare the UK’s leading gold brokers

Compare the UK’s leading gold brokers

If you’re interested in buying gold, our up-to-date directory of the foremost gold brokers and ETF funds makes essential reading.

Compare the UK’s leading gold brokers

The dawn of super-fast trains

Rail transport will also be radically affected by this transport revolution. Despite predictions that cars would make trains redundant, it’s clear that their popularity is growing, with a record 1.5 billion journeys in Britain alone this year.

There are many benefits to encouraging people to travel by train – increased rail use reduces congestion on the roads, and trains have far lower carbon emissions than aeroplanes.

The trouble is, many studies have found that train use drops off rapidly once journey times rise over three hours. So if governments want people to take the train, the trains have to become faster.

High-speed rail (HSR) in itself is hardly new. Japan, partly driven by the pressures of population density, began running regular HSR services between the cities of Tokyo and Osaka in October 1964.

The French also launched their TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse) system between Paris and Lyon in 1981. But it was only from the mid-1990s that HSR began to spread across Europe.

For now, Spain has the largest continental network (1,900 miles), followed by that of France (1,265 miles). The biggest ongoing project is the 1,000-mile Magistrale for Europe, a line that will link Paris with Bratislava in Slovakia. This is due to be completed by 2020.

The most aggressive backer of HSR is the Chinese government. Beijing focused its investment efforts in the early 1990s on improving the often shambolic and slow conventional rail services. But they then moved on to building super-fast lines.

Thanks to successive waves of building, the network is now the largest in the world at 5,800 miles, most of which was built in the past decade.

A crash in 2011, which killed 40 people, and the arrest of the rail minister on corruption charges, forced the network to cut speed limits and scale down future plans. However, the network is still expected to expand to nearly 10,000 miles in length by the end of this decade.

Even America, traditionally hostile to passenger railways, is waking up to the need to increase the pace of rail transport. As part of the 2009 fiscal stimulus package, the US government allocated $8bn to high-speed rail, and has worked with state and city governments to co-ordinate projects.

Central to the proposals is an 800-mile line in the state of California, connecting Sacramento and San Francisco in the north, with Los Angeles and San Diego in the south.

While the plan has been beset by delays and litigation, preparatory work has already begun, with construction due to start at the end of this year. (Although Tesla founder Musk has his own views about high-speed travel in America – see below for more.)

As well as becoming a key part of the passenger rail network, high-speed trains are getting faster. While there is still controversy over what counts as ‘high speed’ (as opposed to merely ‘higher speed’ or ‘fast’), many lines now have maximum speeds of around 200mph.

The fastest train in Europe is Italy’s Frecciarossa 1000 made by Bombardier, which aims to run commercially at a maximum speed of 223mph (though it can go as fast as 248mph).

The next generation of trains may be able to go a lot faster. One technology finally being implemented is ‘maglev’. Instead of moving along a rail track, these trains levitate inches above a path, powered by magnets. The decreased friction means they are much more energy efficient, have longer life spans and can travel much faster.

So far, only tiny showcase lines are operational. However, a Japanese consortium is about to start work on the first part of the Chuo Shinkansen, which will eventually connect the cities of Tokyo and Osaka, completing the 270-mile journey in just over an hour.

The return of supersonic planes

With the fastest rail systems encroaching on markets served by commercial jets, planes are under pressure to get faster too. That’s why the return of supersonic (faster than the speed of sound) passenger planes may be closer than you think.

Concorde, which retired from service just over a decade ago, is often cited as an example of why governments should not attempt to pick winners, consuming billions of dollars in research and development costs.

But it is easy to forget that British Airways managed to make money from its London-New York (and London-Miami) services, suggesting that there was a viable level of economic demand.

Until recently the sonic boom created by breaking the sound barrier was seen as an insurmountable barrier to a supersonic comeback. Public anger about noise pollution, so loud that it rattled windows and damaged roofs, resulted in several countries (including India and America) forcing Concorde to cut its speed over land.

While flights over water were unaffected, these restrictions essentially stopped many routes, such as New York-Los Angeles, which would have ensured the aircraft’s long-term viability. It also prolonged journey times on other routes, reducing Concorde’s advantage over conventional travel.

So far, no solution can completely eliminate the problem, but recent research has suggested several ways in which it could be significantly cut. This makes it more likely that such bans could be partly lifted, perhaps over lightly populated areas and at lower supersonic speeds, such as up to Mach 1.2 (913 mph).

Both Lockheed Martin and General Dynamics-owned Gulfstream have had their own noise-reduction systems tested by the US military on its jet fighters.

Of course, any supersonic aircraft will still have very high running costs, due to the high fuel consumption. However, while this will limit its use in passenger travel, it is unlikely to deter the owners of business jets, who are likely to jump at the chance to cut the times taken to travel to Mumbai (currently 18 hours from New York) and Beijing (14 hours from New York).

To put the cost in context, the most expensive subsonic jets already cost up to $65m, even though they are only slightly faster than far cheaper models.

As a result, several companies are now actively developing supersonic business jets. Privately owned Aerion Corporation says that it is the closest to getting them onto the market with the Aerion SBJ, developed with US space agency Nasa.

This model, which could travel from New York to Tokyo in nine hours (excluding refuelling stops), could be operational as early as 2017.

Aerion claims to have received 50 letters of intent, each backed by a $250,000 deposit, amounting to $4bn worth of orders. It is now seeking to partner with one of the more established manufacturers to build the planes.

San Francisco to LA in half an hour?

Self-driving cars, high-speed trains and supersonic planes are all groundbreaking ideas. However, they pale in comparison to the sheer audacity of Elon Musk’s Hyperloop project.

Musk envisages a giant tube connecting Los Angeles and San Francisco. A combination of magnets and fans would push capsules containing passengers through this tube. Musk believes that near-supersonic speeds could be achieved, allowing people to move between the two cities in half an hour.

What’s more, he thinks that, with the right planning, the project could be carried out for only $3.5bn, with tickets priced at just $20 each.

However, while the idea of people covering the 380-mile distance in less time than the average daily London commute certainly sounds attractive, there are a number of huge problems. The most obvious would be buying the land that the tube would have to go under.

Others argue that if the system broke down, people could end up stranded for hours. One indication that Musk might not have been entirely serious comes from the fact that he has said he will not spend any time developing the idea further.

Even so, engineering simulation company Ansys has said it is feasible, with only minor modifications required.

The six stocks to buy now

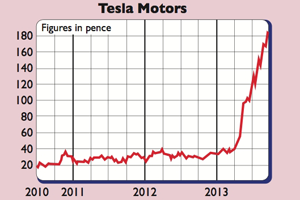

Since we tipped Tesla Motors (Nasdaq: TSLA), the share price has shot up from under $30 to over $180 (see chart). The company is about to start turning a profit, while founder Elon Musk has outlined ambitious future plans.

However, since the price/earnings (p/e) ratio is expected still to be as high as 29 by 2017, we’d suggest it’s time to start taking profits.

Nissan (JP: 7201), which plans to sell a completely self-driving car by 2020, seems much better value, with a p/e of only nine.

The growth of high-speed rail should benefit Alstom (Paris: ALO), which makes some of the best-known high-speed models, including the French TGV, the American Acela Express and the Pendolino tilting trains.

This summer, the French national rail company (SNCF) announced it would exercise its option to place a large order for Alstom’s Euroduplex, the next generation of TGV trains, designed to operate at faster speeds and with a much larger capacity.

This model has the benefit of being inter-operable with the rail systems of other European countries. Alstom also has a strong power-generation unit and trades at nine times 2014 earnings.

Spain’s CAF (Madrid: CAF) is a purer play on rail expansion, since it solely manufactures rolling stock. Its latest high-speed model is the Oaris train, which is currently being tested with a plan to roll it out on the Spanish network, the largest in Europe.

Meanwhile, CAF continues to win contracts to provide rolling stock for standard metro and commuter services, including several in Latin America and Eastern Europe. Its p/e is expected to fall from its current level of 12 to 9.8 by 2015.

Central Japan Railway Company (JP: 9022) is the private rail operator for the central region of mainland Japan (home to around 20 million people).

While it currently operates a mixture of services, it is about to break ground on ambitious plans to develop ultra-highspeed maglev rail, which should help it gain significant market share from the airlines.

While revenues have been hit by the weak Japanese economy, JP Morgan thinks there are strong signs that numbers are starting to grow.

The Bank of Japan’s aggressive monetary easing should also boost the value of the company’s real estate portfolio. It currently trades at only 10.4 times 2014 earnings.

Canada-listed Bombardier (Toronto: BBD.A) makes both high-speed trains and business jets. While it does not yet sell a supersonic business jet, it is due to launch the Bombardier Global 8000 in two years’ time.

This operates at speeds very close to sound. Its part in designing and building the record-breaking Italian Frecciarossa 1000 reinforces its role as a leader in train technology.

Bombardier has also invested heavily in developing a number of technologies to increase energy-efficiency at all speeds. Bombardier has a p/e ratio of 12, declining to 9.1 by next year.

Designing high-speed trains, supersonic jets and systems like Musk’s Hyperloop is a major engineering challenge. One way to cut time and development costs is to use software packages that can simulate many of the problems that engineers are likely to come up against.

One software firm that has substantial experience in working with the rail and aviation industries is Ansys Inc (Nasdaq: ANSS). For example, Ansys has helped Siemens design high-speed trains that can withstand the cold of a Russian winter.

JP Morgan estimates that the simulation market could quintuple as more firms shift to using simulations. Ansys trades at 26.3 times 2014 earnings, but double-digit annual revenue growth is expected between now and then.