Should we be worried about deflation, or will inflation take off again? One reason why many believe inflation will remain subdued is the belief that there is plenty of spare capacity in Western economies. In other words, there is a huge, negative output gap – or gulf between potential and actual GDP – thanks to the brutal recession that began in 2008.

This implies that there is no prospect of demand exceeding supply, and hence inflation becoming entrenched, any time soon: the economy can gradually grow into the capacity that was left idle.

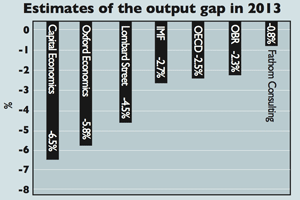

But measuring the gap is more art than science. GDP estimates tend to be heavily revised, even years after the first estimate, so it’s hard to get a handle on output, let alone potential output. Current estimates of Britain’s output gap from various think tanks and institutions (see chart below) range from near zero to 6.5% of GDP.

If the estimates positing a big gap are wrong, the economy will be more inflation-prone than most analysts think.

For instance, during the recession that followed the oil crisis, the US Federal Reserve thought the output gap was vast, and kept monetary policy very loose. But it later transpired that the economy was operating at almost full capacity as it entered the oil crisis.

So, unnecessarily loose monetary policy fuelled the stubborn inflation that bedevilled the US for a decade.

The Fed overestimated the output gap, because it didn’t see that the oil shock had rendered a lot of capacity obsolete – effectively destroying it – as opposed to simply leaving it idle. The same applies after recessions caused by financial crises, studies suggest.

When growth is skewed towards sectors underpinned by unsustainable debt-fuelled demand – in our case housing and consumption – much of the capacity created becomes obsolete once the demand falls away; think countless estate agents and home-improvement stores. So the output gap may be far smaller than many economists think.

Keep in mind, too, that money will move around the economy increasingly quickly as the credit freeze continues to thaw and lending rises. And central banks are in any case not much good at draining liquidity from the system before inflation sets in.

So, the output gap, and the likelihood that it shrank more than expected in the last recession, is another reason to worry that investors can expect inflation to return in the years ahead.