Last week, Greece returned to the bond markets amid applause. Two years ago, the country that sparked the eurozone crisis beat Argentina to take the top spot as the world’s biggest debt restructuring in modern times.

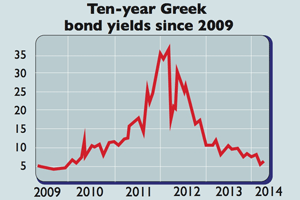

Yet, demand was such – the bond offer was seven times oversubscribed – that it managed to borrow €3bn over five years at a yield of 4.95%. That’s a far cry from the 30%-plus yield seen on its ten-year bonds in the depths of the crisis (see chart below).

Does it mark the end of the eurozone crisis? Hardly. European Central Bank (ECB) head Mario Draghi spent the weekend ‘talking down’ the euro with the threat of some form of quantitative easing (QE).

“The strengthening of the exchange rate requires further monetary stimulus,” said the ECB boss at meetings with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in Washington. The euro has risen by around 6% against the US dollar this year.

A strong currency is deflationary (it makes imports cheaper and hurts exporters). With inflation low or negative across the eurozone, some fear that Europe will turn into Japan.

As a result, ‘unconventional monetary policy’, such as setting negative interest rates (effectively taxing deposits held at the central bank, in the hope that banks will lend) now seems to be on the cards, assuming Draghi can get his way. But that’s a big ‘if’. As one trader told Bloomberg: “talk is cheap.

The market will need to see action for the euro to weaken substantially”. Jens Weidmann, the head of the German central bank, has backed negative rates rather than QE, but is unlikely to back action until the ECB issues a fresh inflation forecast in June.

A strong currency only means more pain for Greece, whose “long-term solvency remains far from certain”, says Wolfgang Münchau in the FT. Yet ironically, now could be the perfect time for Greece to default. It has a budget surplus before interest payments – so it wouldn’t need to borrow to cover its living expenses.

If that debt were forgiven, or defaulted on, Greece could leave the euro and establish a new, weaker currency. The scenario would initially “freak” investors – but they would soon get over it.

A reformed Greece, capable of growth, would be attractive to foreign investors in the ‘real’ economy as well, not just to financial investors like the ones who bought its bonds last week.