Shell’s £47bn bid for BG suggests the oil sector is set for another round of major deals. But investors should avoid getting carried away, says John Stepek.

Mega-merger mania last hit the oil and gas sector around about the turn of the millennium. Back then, the oil price had collapsed to around $10 a barrel. BP bought Amoco and Arco, Exxon bought Mobil, Chevron merged with Texaco, and Total bought Petrofina and Elf.

Now, with the oil price once again collapsing, Royal Dutch Shell “has sounded the starting gun for more mergers in big oil”, says Alex Brummer in the Daily Mail.

Shell has agreed to buy gas explorer BG for £47bn, roughly 50% above BG’s prevailing share price before the bid news came. The combined company will be the third-biggest gas producer in the world behind Gazprom and the National Iranian Oil Company, according to The Economist. It’s the biggest deal in the oil and gas sector for over a decade, and one of the 15 biggest merger deals ever, according to Bloomberg.

As Fortune puts it: “Big mergers in the energy industry typically happen when it becomes cheaper to buy oil and gas reserves on the stockmarket than to drill for them”. But unlike the last batch of mergers, this is more about cost-saving than expansion. “This merger is about squeezing costs out of the supply chain, after a decade in which the industry got fat on the assumption that the demand of China and India for energy could never be satisfied.”

Both BG and Shell are major players in liquefied natural gas (LNG). In the words of The Economist: “Shell is now more gas giant than big oil. This is not easy money… but the market is growing, supplies are abundant and the environmental outlook friendlier than for oil”. The companies are also betting heavily on deepwater oil, and are looking to expand offshore oil output, particularly from Brazil.

Another similarity between the two is that neither company is a big player in US shale – which may not be a bad thing, given that the sector looks particularly vulnerable to the slide in the oil price.

This isn’t the first deal in the oil and gas sector following the slide in prices.

For example, in November, oil services giant Halliburton bought Baker Hughes for £35bn. And it won’t be the last. The chief executive of ExxonMobil has commented on several occasions that he’d be interested in doing another deal. Exxon would certainly like to catch up with rivals in the LNG sector, notes Ed Crooks in the Financial Times. More to the point, boards are now likely to catch takeover fever – they’re driven by the same herd instinct as every other investor.

Meanwhile, investment banks are hungry for fees. So they’ll be whispering empire-building ideas into their ears at every opportunity. “Once deals start being agreed, as in the big oil merger wave at the end of the 1990s, companies tend to start making a rush to reach settlements to avoid being left behind,” says Crooks.

Hence the Shell/BG deal will now act as a “benchmark” that they can compare other deals against in planning their own expansion. As Duncan Goodwin of Baring Global Resources puts it: “we expect this to be the beginning, not the end, of this trend”.

What’s next for the oil price?

So does this deal mark a bottom for oil prices? Oil, as measured by Brent Crude, hit its lowest point of 2015 so far, at below $46 a barrel in January. It’s now trading in the range of $55-$60 a barrel, and there are signs that the price may have hit its nadir.

For one thing, despite initial enthusiasm, the sanction-ending Iranian nuclear power agreement doesn’t look like quite the done deal that it perhaps did earlier this month, which has eased concerns about a massive new wave of supply hitting the market.

What’s more, companies are cutting back on production. Credit ratings agency Standard & Poor’s (S&P) notes that big oil companies are pulling back from expansion plans and cutting jobs. “Some of the big oil firms may need to cut capital expenditure by up to 30% to restore profitability at current prices.”

Meanwhile, the number of US shale oil projects is down by 15% from its peak in October last year. The latest Baker Hughes rig count – which measures how many oil rigs are in operation in the US and Canada – shows that the number of rigs engaged in exploration and production dropped by 40 to 988 in the week to 10 April.

The rig count has roughly halved since October and is at its lowest since December 2010 – at this time last year there were 1,831 at work. So the slide in prices is certainly having an impact. The pretty much unanimous belief is that prices will rebound from here – it might be a while before we see $100 a barrel again, but the bottom is in.

However, as any good contrarian knows, when there’s a consensus, there’s danger. As John Dizard notes in the FT, “the 50% fall in oil has resulted in very few bankruptcies in a highly leveraged industry; just some orderly debt restructurings and takeouts by new distressed fund money”.

For the moment, S&P reckons that the “current low price of crude oil and natural gas is unlikely to have a widespread impact on the credit quality of global project finance debt over the next year to 18 months”.

Projects will “benefit from long-term contractual agreements, break-even points that were designed with low oil and gas prices as a base, the presence of substantial available liquidity to the issuer, or varying degrees of sovereign support”. In short, “we don’t expect to see a significant number of defaults or downgrades in the near term”.

But Dizard is far from convinced that we’ve seen the worst. “When has there ever been a bottom put into a market when inventories have not been liquidated, and when there have been no spectacular bankruptcies? Answer: never.” The problem is that companies in the US are continuing to pump oil – partly because they need the revenues to service their debts.

The US Energy Information Administration expects production to fall, but it still expects more oil to be produced in 2016 than is pumped out this year. “Oil tanks are filling up at a… record rate, far beyond any seasonal bulges.”

The danger is that when and if this excess oil hits the market (rather than being stored) then the oil price will tumble – and “the restructuring plans and borrowing bases collapse” as a result. As S&P’s report puts it: “If prices remain in the US$50 per barrel range for a sustained period or fall further than we expect, the outlook may prove problematic for projects with refinancing risk, market exposure, or input prices”.

This could have a knock-on effect on the wider bond market. As Rebecca Patterson of Bessemer Trust tells Dizard, a further slide in oil prices won’t “just be a commodity story, but a credit story that becomes a market story”.

That’s a plausible scenario, given that bond markets are arguably more overvalued than ever before, and most reasonably sensible market participants are fretting publicly about what might cause the party to end. Of course, even if the oil price does recover from here, something else could trigger a bond market panic, which would still be bad news for over-indebted oil producers.

That’s why we’d be careful of betting indiscriminately on a merger-fuelled comeback for the entire sector – you have to be picky. As Adam Galas of The Motley Fool puts it, “the best way to profit from mergers – in the oil industry, or in general – is to not speculate on them at all. Just buy quality companies with the goal of holding them for the long term”. We’ve had a look at the best ways to play the oil sector right now in the box starting on page 26.

Which oil stocks should you buy?

As far as the big merger story goes, Royal Dutch Shell (LSE: RDSB) has “made a very smart move”, according to Malcolm Graham-Wood of HydroCarbon Capital, writing on malcysblog.com. Buying BG helps the company to focus on “integrated gas and deepwater exploration and development”. It also puts the group in pole position in the liquefied natural gas (LNG) sector, which is likely to become ever more important as a greener alternative to other hydrocarbons.

As for fears over the dividend, Graham-Wood isn’t worried – in all, “the group will have a strong cash-flow engine and generate $15bn-$20bn per annum, which will cover dividends… barring a catastrophe on the oil-price front, this could be a very good deal”. As a result, he reckons the dip in the share price resulting from the big news is a “great buying opportunity”.

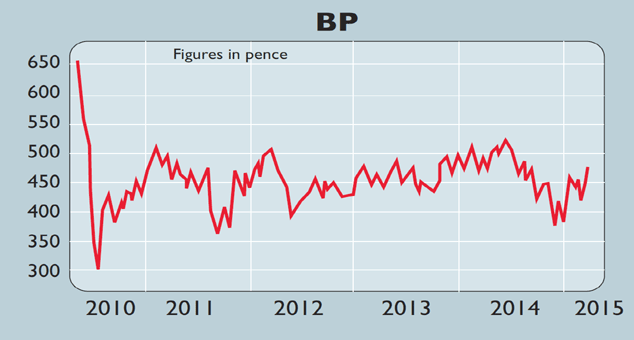

As for other potential deals in the sector, BP (LSE: BP) has long been considered a potential target – for Shell or another company. As The Economist puts it, BP “no longer looks too big to buy”. This deal might “prompt one of its two main American rivals, Chevron or ExxonMobil, to try to regain dominance by making a move”. BP is still tied up in legal battles in America over the Gulf of Mexico spill.

However, one can imagine that its acquisition by a big American oil giant, in which many more domestic investors have a stake and which would also be very keen to come to a decisive deal, might help to resolve some of the trickier outstanding issues.

As Roland Head points out on The Motley Fool, BP would help ExxonMobil (NYSE: XOM) cement its status as the largest listed oil and gas producer in the world. And it would also “give a significant boost to Exxon’s reserves”.

Exxon is very much the “apex predator”, as it were, of the oil and gas sector. It’s also well known for its efficiency and might be able to squeeze more profit out of BP’s business. Exxon itself also looks like a decent investment at current levels – it’s a “dividend aristocrat”, having raised the dividend for at least 25 years in a row, and it currently yields around 3%.

Exxon rival Chevron (NYSE: CVX) is another dividend aristocrat, trading on a yield of nearly 4%. Broker Jefferies has a price target of $125 on the stock (from around $110 now), noting that the “progressive dividend” is a priority for the company and that it has the flexibility to cut capital spending if necessary, which should mean the payout is well covered.

Moreover, if you’re worried about CEOs splashing the cash on empire-building, the analysts argue that “given Chevron’s strong organic growth outlook, we do not expect them to be in the market for a large acquisition”.

If you’re in the market for a potential target that’s a bit more adventurous than BP, some London-listed oil companies that analysts have flagged up as vulnerable include Tullow Oil (LSE: TLW) and Premier Oil (LSE: PMO).

Both have seen their share prices slide in the past year along with the oil price, but both own assets that might be attractive to deal-hungry oil majors. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Paul Sankey of Wolfe Research has flagged up a number of shale oil targets that Exxon could be interested in.

These include Hess (NYSE: HES), Continental Resources (NYSE: CLR), Devon Energy (NYSE: DVN), Apache (NYSE: APA) and Anadarko (NYSE: APC). However, if you’re interested in the shale sector, you might be better off buying a simple exchange-traded fund, such as iShares Oil & Gas Exploration & Production (LSE: SPOG), which holds several of these shares.

Another interesting way to take advantage of turmoil in the oil and gas sector is via Riverstone Energy (LSE: RSE). This FTSE 250-listed closed-ended fund has had the backing of oil industry grandees, including ex-BP CEO Lord John Browne (who is stepping down as a director of the fund next month).

The fund was created by private-equity group Riverstone Holdings to invest in “opportunities in the exploration and production and midstream sub-sectors”. Arguably, if there’s a good time to be hunting for bargains in the oil and gas sector, it’s now, so this trust could be a good way to profit from the fallout of the tumbling oil price.

If you’d rather invest in the energy sector using a traditional fund, your options include Artemis Global Energy, Investec Global Energy and Guinness Global Energy. These funds have all had a tough time over the past year or so as you might imagine.

Going back over three years, Guinness is the strongest performer (down just 1.4%), while Investec is down around 12% and Artemis down 39%. Guinness has a bit of exposure to solar power, while the other two funds are mainly invested in oil and gas.

The team at Guinness expects “oil to trade in a $50-$70 range in the near term”, but if “this price range persists, we expect North American unconventional supply growth to slow rapidly. This points to a rise in oil prices in the second half of 2015/first half of 2016”. In the longer run, Guinness expects a recovery back towards $100 a barrel.

The ten biggest mergers

According to Bloomberg, these are the ten biggest mergers of all time. The Shell/BG deal would come in at around twelfth position.

| Companies | Sector | Year | Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| AOL/Time Warner | Tech | 2001 | $186.2bn |

| Vodafone/Mannesmann | Telecoms | 2000 | $185bn |

| Verizon/Vodafone | Telecoms | 2014 | $130bn |

| RBS/ABN Amro | Banks | 2007 | $100bn |

| Pfizer/Warner-Lambert | Drugs | 2000 | $87.3bn |

| AT&T/Bell South | Telecoms | 2006 | $83.1bn |

| Exxon/Mobil | Oil | 1999 | $80.3bn |

| Royal Dutch/Shell | Oil | 2005 | $80.1bn |

| Glaxo/SmithKline | Drugs | 2000 | $79bn |

| Comcast/AT&T | Telecoms | 2001 | $72bn |