The single currency just can’t work without political union, says economist George Magnus.

• Watch the whole interview with George here.

When I met George Magnus, Chancellor George Osborne was soon to start his Budget speech, Greece had just voted not to accept Europe’s deal, and China’s stockmarket was in freefall – down 30% in a matter of weeks. We started with China. Crash or correction? Magnus reckoned correction. The “market did go up by 150% between June 2014 and early June of this year”, so most investors will still be in profit, making this just a correction in “an extraordinary appreciation of stock values”.

I say that, while most people are using the word “bubble” to describe China, Magnus very deliberately isn’t. Why not? China is not a market “in the way that we understand markets”. Instead, “the fingerprints of the [Communist] party are certainly on what has happened”. Note, for example, the “rhetoric from the central-bank governor and from members of the State Council, about how good a rising stockmarket would be for the economy”, as well as the Hong Kong-Shanghai Connect scheme.

These are both designed to bring money into Chinese equities. China has overcapacity, rising debt and slowing growth. It is also trying to pull off a “very difficult economic transition”. Asset price inflation can help with that. It makes the balance sheets of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) look better, and it “encourages companies to shift their financing from debt to equity”.

The problem is they let it go too far, too fast – allowing too much margin debt (when investors use borrowed money to buy stocks), for example. Now they are using a “panoply of measures” to try and support the market. Is that possible? They have “a lot of money they can throw at it”, but now they have a problem: the correction, and the attempts to stop it, have affected “the confidence that people, and Chinese people in particular, have in the state and government authorities to manage the market, and, implicitly, to manage the economy”. Not a buyer of the Chinese market then? No.

After a nasty short squeeze, and until there is real reform of SOEs and a grasp of how private capital is supposed to participate in share ownership, “this market is going back to where it came from”.

The government clearly can’t manage the market that well. But what of the shift to a slower-growing economy with a consumption bias? There are two bits of good news, says Magnus.

First, the economy will rebalance regardless. The investment rate in China is around 50% of national income. It’s starting to fall and “by definition as the investment rate goes down the consumption rate goes up”. But what people just don’t get is that “this can only happen in the context of significantly lower growth”. Consumption growth is already 7%-8% a year (“it’s not as though Chinese consumers have been slouches”).

It won’t grow much faster than this, so as investment growth falls below the rate of GDP, leaving consumption growth above it, the aggregate growth rate will slow – “I think over the next three to five years it’s going down to about 4%.” That’s not a disaster, but it “has already taken commodity producers from Perth to Peru a little bit by surprise, and I think it will take a little while for people to get used to the idea that China’s growth rate is pedestrian”.

Is it possible to avoid Grexit?

We move on to Greece. Magnus and I were talking just before last weekend’s meeting, but at the time we both felt the odds of “Grexit” were high. What would that mean for Greece and for the European project as a whole? The Greeks already feel they are living in an economic disaster, says Magnus. But while a lot of academics seem oddly keen for Greece to make its own way, the truth is that, “given Greek history, the difficult structure of the Greek economy and the absence of manufacturing… actually life outside the euro would be a catastrophe”. Tourism would get a boost. The new drachma would drop by 40%-50% and those who have been going to Turkey would shift over. But Greece just doesn’t have much else.

Hmm. But doesn’t his certainty that the new drachma would fall by 40%-50% tell us that the euro is the wrong currency for Greece (it’s just too high)? Perhaps, says Magnus. But if you asked the Irish or the Portuguese about this, they would say that they have dealt with the same problem with internal devaluation (pushing down wages and costs to make their goods competitive). It is difficult and painful, but it is also “one of the rules that goes along with monetary union”. We have “huge regional disparities” in the UK too.

Hmm again. We do, I say, but it works because the core of the UK transfers large amounts to those regions to compensate. The core of Europe clearly isn’t willing to do the same – which is why Europe is failing. This, Magnus agrees, is the “key point… Monetary unions that work, such as the United Kingdom or the United States, or the Federal Republic of Germany, work because they have been preceded by the political integrations, the political union that enables those transfers to happen.” So Europe is “a unique experiment in trying to put the cart before the horse… to do the monetary union and then to do the political union”.

It isn’t working that well. And it could end. If Greece leaves we will see that “the euro isn’t really a single currency, but a system of fixed, but breakable, exchange rates, which means that even if the whole feared contagion is contained now, in a future crisis it might not be, particularly if a big country like Spain or Italy were involved… the acid test for Europe now is – can it seize this moment as an opportunity to persuade sceptical citizens that this is the time for greater integration?” If they fail, there is an outside chance, in extremis, “that the whole thing just blows up and we go back to national currencies all over”.

Would that be a bad thing? Magnus’s immediate response is that, given the 60 years Europe has spent on integration, it would be horribly traumatic for everyone. But then he tells me about Dani Rodrik, a professor of economics at Harvard, and his “globalisation trilemma”.

“Imagine a triangle, and label the points: economic integration, national sovereignty and democratic politics. His argument is you can only ever have two of these three, unless you have trusted, respected institutions to integrate them… That’s really where Europe has been found out… we don’t have the trusted, efficient institutions” and that threatens democracy and sovereignty. “You see that in the rise of anti-EU parties and so on, and regionalism… people are… saying: ‘Actually, this national sovereignty, democratic politics malarkey is something that we care quite a lot about’.”

Central banks run out of ammo

Speaking of institutions we don’t quite trust brings me to the central banks. I wonder if he sees some of the world’s problems right now (Greece, China) as we do – as proof that central banks just aren’t as all-powerful as we might think. They can’t rescue China and they can’t rescue Greece. He does. “I think we have asked far too much of central bankers.” Governments have failed to step up to the plate in terms of policy – and we have allowed them to do this – so the banks have had to step in with innovative monetary policy.

They now have no ammunition left for the next major crisis, which – Magnus reckons – means they will end up “the fiscal agents of the government – buying government debt directly from the government without bothering with the middleman of the banks. Pure debt monetisation.” At that point, the idea that central banks are independent certainly has to be re-examined and you also have to “have a discussion as to whether that’s exactly what you thought you wanted central banks to do”.

We talk about interest rates. If the central banks want to have ammo for the next crisis they need to get rates up before it starts. Can they? “In Japan and in Europe it’s not going to happen for quite a long time. But after a terrible start to the year, the American economy does seem to be regaining a little bit of momentum.” If we see some traction with wages, the Federal Reserve might “find the wherewithal to bite its bottom lip” and get on with it. “Of course there’s a subsequent question about how far will policy interest rates rise over the next couple of years. And that may not be very far.”

What of inflation? Do we have to worry about that at all? Not in the next 12 months, says Magnus. But ask again in 12 months’ time, and the answer might be yes, “because when it happens I think it will happen quite quickly and unexpectedly”. We don’t want to get carried away yet, but there are certainly signs around the world of wages ratcheting up. Magnus, who is also an expert on demographics, points out that this is something we should expect in the future. Our ageing society means that “over time we will experience labour and skill shortages”.

So rewards to labour will go up relative to capital. That means that returns to equity won’t be as good as they have been in the past – driven as they have been by zero rates, quantitative easing, and expanding profit margins. That might not sound great for investors. But on the other hand the market probably won’t crash. And rising returns to labour is good for labour. An hour after this discussion concluded, George Osborne raised the UK’s minimum wage to £7.20 an hour from April.

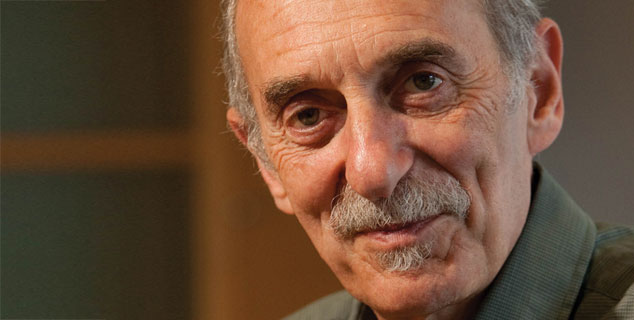

Who is George Magnus?

George Magnus, 65, is an independent economist, consultant and author, with a long background in the financial services industry. He spent his early career with Lloyds Bank International and Bank of America, before moving to UK stockbroker Laurie Milbank in 1985, then to SG Warburg in 1987 as head of fixed income research, and later chief economist. In 1995, he moved to UBS as chief economist, and from 2005 to 2012 was the bank’s senior economic adviser.

Magnus is widely credited with predicting the financial crisis, warning in March 2007 that the US subprime mortgage slump could end with “potentially systemic economic consequences”. As he told The Daily Telegraph in November 2008, “it’s always nice to be right… but it’s not pretty”. His first book, The Age of Ageing (2008), dealt with shifting global demographics. His second, Uprising: Will Emerging Markets Shape or Shake the World Economy? (2010), offers an in-depth take on emerging markets and China in particular.