“August does seem to specialise in episodes of market turmoil,” says Economist.com’s Buttonwood blog. August 1998 saw Russia’s default; August 2007 was when the subprime crisis really started to bite; and four years later the eurozone crisis threatened to spread across the region’s peripheral nations.

This time, European stocks have suffered their worst August since 2011, with the pan-European FTSE Eurofirst 300 index down 9%.

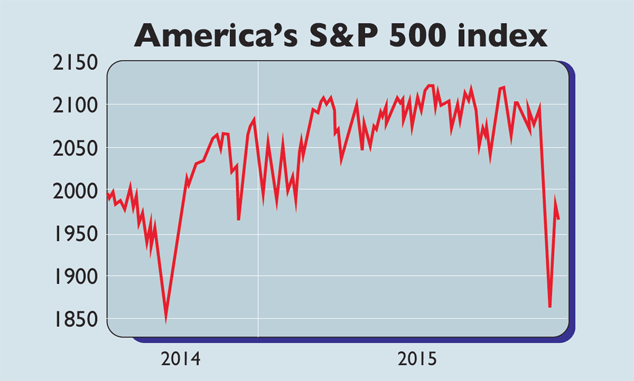

Many investors will have been horrified by the sharp falls early last week. The Dow Jones index opened 1,000 points lower at one stage, and blue chips such as General Electric lost 20%. Around 40% of the world’s stockmarkets were plunged into bear market territory (defined as a decline of more than 20% from recent highs), according to research from Absolute Strategy. The majority of them – 80% – slid by more than 10%, the definition of a stockmarket correction.

One reason August often sees such violent moves is that many traders and investors are on holiday, so liquidity drops (buying and selling tends to move the market more than it otherwise would), while the rattled junior staff members temporarily in charge of funds may be wary of acting as buyers once prices fall. The spread of computerised trading doesn’t help either, as these programmes can “feed on each other”, or simply get switched off in a crisis, notes Buttonwood.

Black Monday fades to grey

But by the end of last week, major markets had jumped back to their Black Monday starting point. “Markets fell too far, too fast,” as James Mackintosh pointed out in the Financial Times. The bears worried that a sudden Chinese slowdown would “eviscerate commodities, ripping through emerging markets and dumping deflation and recession on the US, Europe and Japan”.

But so far, the Chinese data provide little evidence of a sharp slowdown – certainly not a sharper slump than investors should already have been aware of. Investors cheered up when the Chinese central bank cut interest rates, while the US turned out to have grown much more strongly in the second quarter than first estimated. It grew at an annualised rate of 3.7%, 1.4% up from the first reading.

A Federal Reserve official then said a September interest-rate hike seemed “less compelling” than before the turmoil. The US market, which often sets the tone for the world, is especially jittery about higher US rates this time round because American earnings growth is turning negative, as US investment adviser Peter Bernstein points out. Normally, just before a rate hike, earnings are increasing rapidly, reflecting a strengthening economy, and the Fed raises rates to prevent overheating.

But earnings growth has faded away, and with profit margins at historic highs, there is scant scope for yet more cost-cutting to lift earnings. Valuations are high too, adds John Authers in the FT. So the American market was very vulnerable to a correction; China fears were merely the trigger.

The bear will stay away for now

August’s jitters seem unlikely to lead to a bear market yet, however. As several analysts have pointed out, US bear markets are almost always accompanied by recessions, and while the economic recovery has been subpar, it looks strong enough to cope with a slight increase in interest rates. More to the point, such an increase may not even materialise now.

As we noted last week – and as Capital Economics reiterated this week – if there is a downturn, central banks still have a wide range of measures they can employ, from printing more money to promising to keep interest rates lower for longer, keeping liquidity flowing into asset markets. There are still plenty of problems with the world economy – but this squall seems likely to pass.