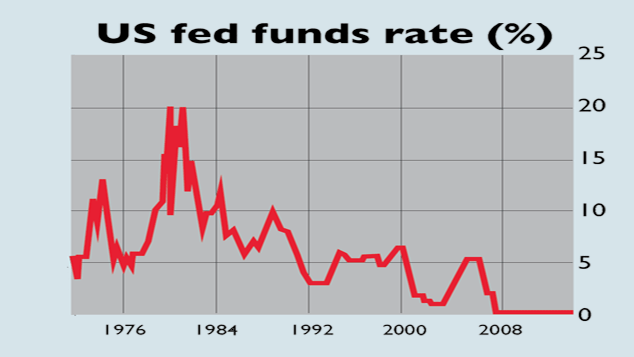

Finally. Ever since the benchmark US short-term interest rate, the federal funds rate, fell to a record low of 0%-0.25% in 2009, the Federal Reserve has “repeatedly made optimistic forecasts about when they would start rising, only to delay the big day again and again”, says The Economist. Now we finally have lift-off. Last Wednesday, the US central bank lifted the funds rate by 0.25% to a new range of 0.25%-0.5%. It was the first such rate hike since June 2006.

No tantrum this time

Fed chair Janet Yellen had a delicate balance to strike, as John Authers notes in the Financial Times. She had to pre-empt a possible rise in inflation “without triggering a market spasm that would endanger financial stability and the economy”. Her task was akin to “removing an iPad from a child’s grip without a meltdown”. Markets threw a “taper tantrum” when the Fed signalled in 2013 that it would reduce the pace of quantitative easing (QE), or money printing, and there were further wobbles last spring when it signalled that rates could soon rise.

This time, however, liquidity-addicted markets weren’t perturbed; indeed, stocks ticked up once the decision was announced. The move had been clearly telegraphed; recent economic data have been positive; and the global-market jitters that had helped persuade the Fed to hold fire in September had subsided, although the turbulence in the credit markets has caused concern. Yellen also placated investors by making it clear that rate rises from here will be very gradual.

Many analysts believed it was high time for the Fed to move. Its mandate is to achieve maximum employment and 2%inflation. Unemployment has slipped to just 5%, below the level at which the Fed last started tightening in 2004. Underlying inflation, which strips out volatile food and energy prices, has already reached an annual rate of 2%.

The big picture, however, is that “America’s monetary policy has just gone from being astonishingly loose to ever so slightly less astonishingly loose”, says Liam Halligan in The Sunday Telegraph. There’s miles to go if we are to return to interest rate levels usually associated with “normality” rather than an emergency.

Early signs of trouble

But how far will we get? The market may have shrugged off this first hike for now, but “the real test for the wider financial system has barely begun”, says Gillian Tett in the FT. Years of ultra-loose monetary policy have blown up bubbles all over the place, notably in the credit markets. Some fear the latest turbulence in the junk-bond market could be an early sign of another crisis. Banks look capableof absorbing losses in US corporate debt, but a series of defaults could trigger contagion and widespread volatility, especially as liquidity has receded in bond markets because banks no longer tend to act as market makers, says Tett. Note too that fund managers, in their desperate quest for yield, have piled into riskier long-term assets, raising their portfolios’ vulnerability to higher rates to historic highs. If market contagion breaks out, interest rates would have to fall again and QE might even restart.

An unexpected surge in inflation could also cause turbulence and cause interest rates to be hiked much faster than currently expected. The inflationary momentum could come from wage growth. In December the annualised rate of average hourly pay growth hit 2.8%, up from 2.4% in September. And core inflation is already at 2%.

The Fed’s serial bubble blowing, then, means that getting rates up significantly without endangering the system is going to be a very tall order. The last time the Fed embarked on a similar exercise was in 1947. Back then, it started raising rates from three-eighths of a percent, where they had been for five years, says The Economist. “This time, the wait for another stint near zero may not be nearly so long.”