Many FTSE 100 companies are paying out dividends that exceed the shortfalls on their company pension schemes, leading some commentators to question whether firms are putting enough of a priority on ensuring that employees’ pensions are adequately funded.

In total, 54 FTSE 100 companies have handed out £48bn to investors in the past two years, almost equal to the deficit of their combined pension schemes, which stood at £52bn in 2014, according to figures compiled by stockbroker AJ Bell. Some 35 companies have paid out more in dividends than the total size of their pension deficits.

For example, oil major Royal Dutch Shell paid £8bn to shareholders last year despite having a £6.7bn funding gap in 2014. Pharmaceuticals giant AstraZeneca paid £2.4bn, compared with a £1.9bn deficit the previous year, while GlaxoSmithKline handed out £3.9bn despite a £1.7bn gap in 2014. Rio Tinto, National Grid, Glencore, British American Tobacco and Vodafone were also among the biggest spenders.

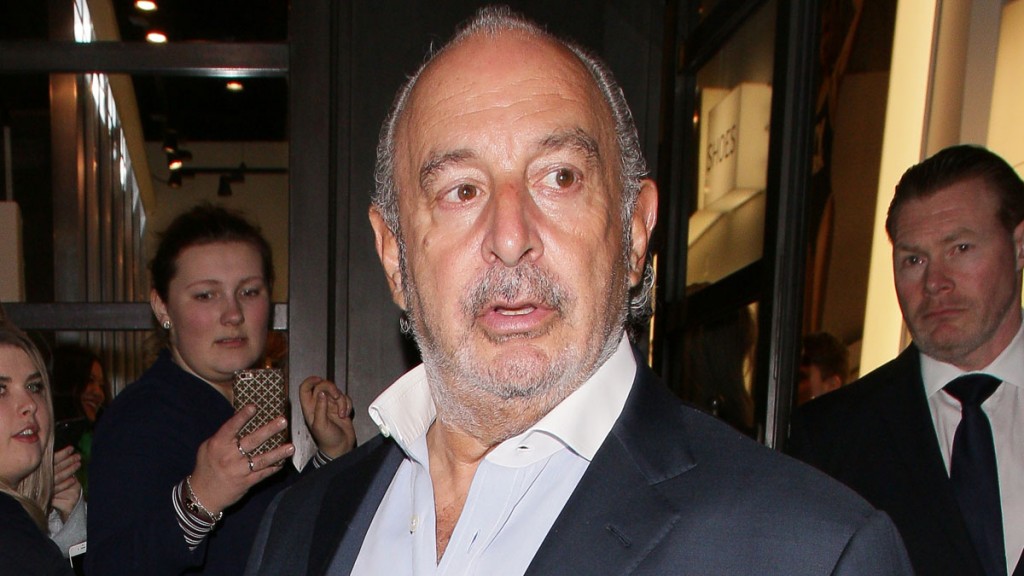

Numbers such as these easily generate controversy, given the extent to which pension deficits have been in the news lately. Last week, Sir Philip Green faced the Work and Pensions Select Committee to discuss the collapse of retailer BHS, which has left a £571m deficit that will need to be absorbed by the Pension Protection Fund (the pensions “lifeboat” that partially protects staff pensions if their company pension scheme becomes insolvent).

Meanwhile, the government is consulting on plans to restructure benefits paid by the British Steel pension scheme (see below) in order to tackle that scheme’s £485m deficit. But is there really a case for firms with large deficits to suspend or reduce dividends and funnel the excess cash into their pension schemes?

There are two main problems with simplistically comparing dividends to deficits in this way. The first is the question of what deficits actually measure. As MoneyWeek’s editor-in-chief Merryn Somerset Webb noted last time this subject came up in April, “A pension deficit is not a number that is set in stone… It’s an actuarial concept based on best guesses about future investment returns.”

In most cases, it’s calculated on the assumption that the pension fund’s returns will be around the level of the yield on UK government bonds (gilts). The lower the gilt yield goes, the worse the deficit becomes – and that’s what’s been happening in recent years, as yields have headed to record lows.

Many funds are now heavily invested in gilts – for many years, they were encouraged to be, as the safest and most prudent option. However, bonds show every sign of being in a bubble (see page 24) – basing an investment strategy solely around gilts is madness. Instead, the sensible approach would be to invest elsewhere in assets and earn a higher return – which would make their deficits look less onerous.

The second issue is that the obvious place for pension funds to invest in pursuit of higher returns is in equities. These may not be cheap, but dividend yields are significantly higher than bond yields and offer pension funds a higher income stream. However, if firms cut dividends to plug deficits, that will reduce the returns that pension schemes can earn from equities. In short, slashing much-needed dividends to plug overstated deficits could make corporate pensions’ problems worse – as well as hitting lots of other shareholders who also depend on dividends.

Abracadabra, the deficit is shrunk – but is the magic legal?

Last week, the FirstGroup Pension Scheme, which provides retirement benefits for many employees of bus and train operator FirstGroup, revealed it has switched its measure from the Retail Price Index (RPI) to the slower-rising Consumer Price Index (CPI). While this may sound like a very technical change, the shift will enabled the scheme to wipe £10.8m from its liabilities, making it a useful example of how seemingly minor issues can affect the size of a pension fund’s deficit or surplus.

RPI and CPI are calculated differently, resulting in RPI producing a rate of inflation roughly 1% higher than that produced by CPI. Since defined-benefit (also known as final-salary) pension schemes mostly increase what they pay in line with inflation each year, the measure of inflation they use affects how much they are likely to have to pay in future and hence how large their estimated liabilities are.

Since 2010, CPI has been used to measure annual increases to public-sector occupational pensions. However, many private-sector workplace pensions have stuck to the more traditional RPI. The Department for Work and Pensions has estimated that roughly three-quarters of schemes have rules that stipulate that inflation-linked increases are based on RPI. In the case of the FirstGroup Pension Scheme, this stipulation did not apply. The trustees were permitted to select an appropriate measure of inflation, which had previously been RPI but will now be moved to CPI.

Most other pension schemes do not have this flexibility, which is why proposals to restructure the British Steel scheme are so controversial. The government is considering allowing this scheme to switch its inflation index from RPI to CPI, even though the scheme rules specifically lock it into RPI. Thus the change would not usually be permitted under the Pensions Act 1995, which prohibits retrospective changes to benefits that have already built up, unless members consent.

The British Steel scheme is being described as a special case. The change would cut an estimated £2.5bn from the scheme’s long-term liabilities, and thus make Tata Steel more attractive to prospective buyers, potentially saving up to 40,000 jobs, and preventing the scheme from falling into the Pension Protection Fund. However, the reality is that if one scheme is allowed to bend the rules, others will eventually be permitted to follow.