I don’t believe in the Great Men theory of history, says Rupert Foster. But all China’s latest great man has to do to succeed is keep calm and carry on…

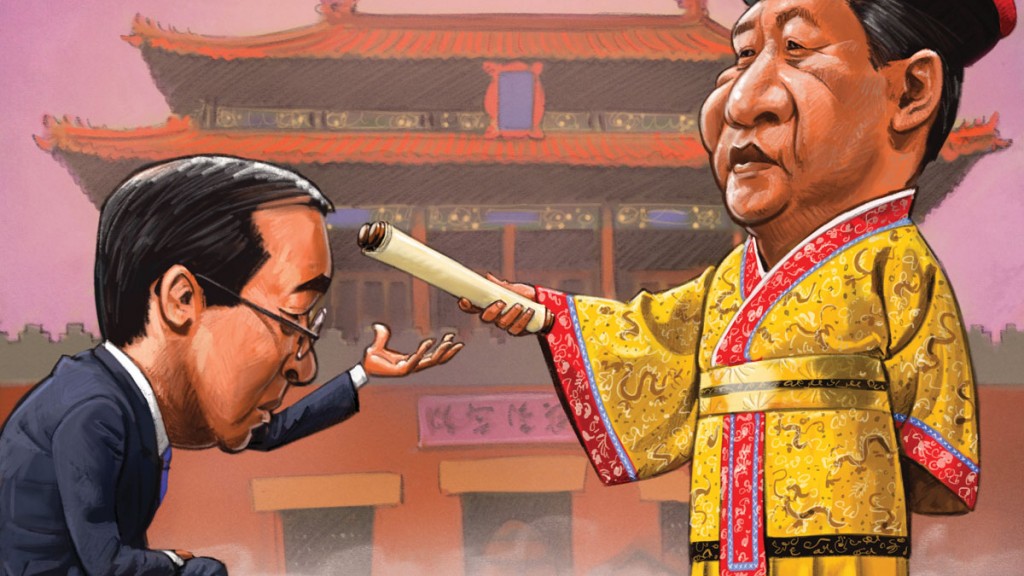

As a historian with a revisionist bent, I disagree with Thomas Carlyle’s statement that “the history of the world is but the biography of great men”. However, when assessing China’s development, we need to spend time focusing on President Xi Jinping, particularly after he was named the “core of the party” at the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee meeting in October. Will this give Xi the power he needs to advance his previously announced, but as yet undelivered, reforms? Or were those promises always a “bait and switch” – was his real aim to cement power for the CCP and for himself? The answers are key to what happens to Chinese equities – and to the fortunes of those who invest in them – over the next five years.

A well-trodden path to growth

China’s development has so far followed a well-trodden path. It is the fourth south Asian country after Japan, South Korea and Taiwan to follow the “control economy development model”. This is where you see a period of hypergrowth (GDP growth averaging above 8% a year), fuelled by infrastructure investment and foreign capital inflows, attracted by booming export growth and cheap local wages, followed by a “transition moment” when GDP per head reaches around $7,000 (on a purchasing power parity basis). The transition begins when early infrastructure needs are met, and wages rise. At that point, consumer demand is needed to fuel further growth as the middle class grows. GDP growth slows to around 2%-4% a year, but this does not matter to investors – Japan’s market rose by more than 350% in the decade after 1969 (its transition moment).

At each stage, the countries’ key economic metrics have been pretty similar. Where China differs is in its very high debt levels, and surprisingly low level of urbanisation, which has resulted in weak consumption growth. Even so when China’s transition moment came in 2007, there was every reason to believe it would follow the same trend as its Asian peers. But then the 2008 financial crisis came along. Guangdong province, China’s manufacturing hub, saw huge job losses. China’s government, fearing worker unrest, poured four trillion yuan into the system, sending Chinese shares higher and spurring a global economic recovery in 2009. However, the easy money poured into increasingly wasteful projects, while the collapse in Western consumption demand – which had so helped Japan and South Korea’s development – saw China’s leaders forced to rely on vast credit growth to make the average Chinese national feel that his or her quality of life was improving. The main problem is the lack of reform over the last few years. Xi was appointed general secretary of the CCP in 2012. In November 2013, he announced an aggressive reform plan at the Third Plenum of the Central Committee. Third Plenums have been used by past leaders to announce key policies, so this seemed to bode well. But very little of what became known as the “383 Scheme” has come to fruition in the past three years, and that’s all down to the internecine politics of the CCP.

Since Mao, Chinese policy has effectively been controlled by two “core” leaders, Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin. Deng was the core leader from 1978 to his death in 1997, despite giving up his last official CCP job in 1989. Jiang had been general secretary of the CCP since 1989, but only took control after Deng’s death. He then kept it until Xi’s promotion in 2012. Jiang had ceased to be president and general secretary of the CCP in 2002, but kept control throughout Hu Jintao’s presidency. Jiang’s chosen successor was Bo Xilai. Xi and his allies outmanoeuvred him, but Jiang and his supporters remained a very powerful group in the CCP, making it hard to force through changes. However, Xi’s high-profile “anti-corruption” drive has provided cover for the arrest of Bo Xilai and Zhou Yongkang, the two leading active Jiang group figures. It is now rumoured that Jiang’s son and possibly Jiang himself are under house arrest. The process has moved at a “CCP pace” – always disappointing for short-termist financial markets. However, it has finally resulted in Xi’s self-anointment as the new CCP “core”. In turn, his reform agenda of 2013 should now pick up pace.

For investors, the key reforms are those that quicken China’s shift to a consumer economy, and encourage better allocation of resources. On the first point, land ownership and social security reform are key. Today, Chinese peasants cannot sell the land they were given in Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, and so many maintain their rural connections. This is one reason why urbanisation in China is about 15% (roughly 200 million people). This matters, because China’s rural dwellers earn and consume about two-thirds less than urban dwellers. So encouraging urbanisation would boost consumption as well as infrastructure spending, and may also soak up the oversupply of housing in China’s less developed (Tier 4 and 5) cities. In September, China’s State Council reiterated a plan to force 100 million rural dwellers into cities by 2020 – this may now be enacted.

The second key policy is social security reform. China’s savings rate is so high because the Chinese can’t rely on the state for their education, healthcare or pensions. The easiest way to start changing that is to scrap rules that stop China’s 300 million rural migrant workers from receiving social security in the cities – another big potential consumption booster.

Improving resource allocation is all about reforming large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and giving the market a larger say, particularly in finance. We’ve seen small achievements here already. The mergers needed to cut overcapacity and raise competitiveness are taking place at a faster rate than similar reforms ever did in Japan. Other reforms have slowed. Assigning credit correctly is at the core of any modern economy – if money is assigned in a corrupt fashion, growth is likely to stall. In China, the main banks are all SOEs. They mostly lend to other SOEs, even though the most vigorous businesses are in the private sector. The government has allowed the launch of non-SOE banks, but the process has been hampered by pressure from existing banks. Leading internet groups Alibaba and Tencent should be given a freer rein to compete in the sector.

One area the government can’t do much about is the need for China to create quality home-grown products that “go global”. In the early 1970s, Japanese goods were seen as cheap rubbish. By 1979, Japan was leading the world with the Sony Walkman. I would have expected China to produce some world-leading products by now – laptops from Lenovo don’t cut it. But there are signs of change. Shanghai-based internet start-up musical.ly has recruited 100 million US users for its combination of karaoke and streaming. Elsewhere, Walmart may have abandoned its own e-retailing ambitions after buying a 10% stake in JD.com, the third-largest ecommerce company in the world (behind Alibaba and Amazon). One way in which the government is helping is via the funding of foreign mergers and acquisitions. This year, China was the world’s largest buyer of foreign firms, spending more than $160bn – up more than 50% on last year.

One byproduct of Xi’s ascent to the throne could be a rebound in the beaten-down Chinese luxury sector. Since 2013, luxury goods consumption has stalled as no government official or private individual has wanted to flaunt their wealth. However, court cases for corruption are down 50% on last year, and Xi’s ascension should allow him to take his foot off the neck of the CCP. Even if luxury consumption regains just half its previous levels, that would represent a dramatic year-on-year increase.

What the bears say

What about the bear case? The bears focus on two things: debt and capital flows, and either could derail the growth juggernaut. There is no reason to expect a 2008-style crisis because the central government will in the end own both sides of the credit risk on 70% of all official debt, so they can manage the process. Two new approaches adopted by the government in 2016 – swapping debt for equity and securitising loans – will help this process by officially moving the credit risk closer to the central government. Along with tactical write-downs, that should allow overall debt growth to stabilise over the next few years. If not, the central government could be submerged in debt fears, and China will fall off its development path.

Capital flows are a bigger issue. Chinese nationals are allowed to move $50,000 out of the country each year. China’s money supply is $20trn, so its $3trn foreign-exchange reserves would be unable to offset any concerted effort by Chinese nationals to buy foreign assets. The term “capital flight” is unfair – a 10% shift of liquid capital into foreign assets would be seen as “risk diversification” in the West. But even that level of diversification in China would cause a collapse in the yuan. Last year, around $700bn left China, and a further $500bn seems to have left this year – but a mere 10% diversification would mean a $2trn move. Until China can convince Asian central banks to use the yuan as a reserve currency (which would mean those central banks holding it in large quantities), they will have to put up with a steadily devaluing currency, with occasional spikes on fear of a more concerted devaluation, or most importantly, the fear of a genuine loss of control. The attempt to free float the yuan highlights one big problem for any Asian government at this stage of development. If you are meant to be in control of the currency, the stockmarket grows to need that sense of control to feel comfortable. But if the yuan is to become a true reserve currency, it needs to at least be seen as a free-floating currency. And that means loss of control.

That said, the election of Donald Trump in the US should ease China’s currency problem. If the US abandons the TPP trade deal, many Asian nations will turn to China. One quid pro quo for China will be the adoption of the yuan as an Asian reserve currency. However, the $50,000 annual allowance restarts in January each year, so in the short run, a surge of capital flight is possible, particularly amid fears that the allowance will be taken away. As for Trump’s approach to China – the Chinese may struggle to combat the US’s likely tax reforms, which will encourage businesses to build factories for US-consumed goods in the US. However, as the benefits of cheap wages and improving productivity have largely played out in China, this will not affect Chinese employment significantly.

Tolstoy, a famous disbeliever in Carlyle’s “Great Men Theory”, wrote in War and Peace that Napoleon at the Battle of Borodino acquitted himself well in his role as commander by just “appearing to command calmly and with dignity”. The same could be said of Xi, particularly in a country that puts such value on “face”. If he can just “keep calm and carry on”, the China bulls will reap the rewards of their foresight and limitless patience.

China’s internet giants seek global dominance

The best large Chinese businesses are all in the internet sector. Rather conveniently for UK investors, all of them are listed outside of China. They are Alibaba (NYSE: BABA), Tencent (Hong Kong: 700), Baidu (Nasdaq: BIDU), Ctrip (Nasdaq: CTRP) and JD.com (Nasdaq: JD). These businesses have no earnings correlation with their Western equivalents, but perceptions about the strong growth outlook for the entire internet sector mean that they have been re-rated higher alongside America’s FANG (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google) stocks. This means they are open to any correction that hits their US peers. However, this would present a wonderful buying opportunity.

Why? Because China’s internet giants enjoy much stronger market positions than their US counterparts. In China, unlike in the US, older brands have limited power or market share. As a result, the three largest internet businesses, Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, are now China’s most-trusted brands across a wide range of industries – they are the new monoliths of corporate China. The big question is whether they can achieve global dominance as well as domestic, but today’s valuations factor in nothing for overseas expansion. Trump may dampen their ambitions to enter the US market, but the real excitement is about dominating the emerging world – and particularly the rest of Asia.

In the short run, the most attractive name is probably Tencent. Domestic Chinese investors have just been allowed to invest into the Hong Kong stockmarket via the Shenzhen market (China’s equivalent of the US Nasdaq). In Shenzhen, second-tier internet firms trade on 100 times earnings, whereas the best and the strongest, Tencent, trades on just 35 times. The flow of money from investors will be slow at first, but 2017 looks like being another strong year.

If you would prefer to invest in China via funds, I would suggest the following, which have an exceptional record over many years: Baillie Gifford Greater China Accumulation, Stewart Investors Asia Pacific Leaders, Jupiter Asia Income and Fidelity China Special Situations.