China may now have more billionaires than America. In 2000, it had just one. That should be good news – but some of them are feeling very nervous. Alex Rankine reports.

How many tycoons does China have?

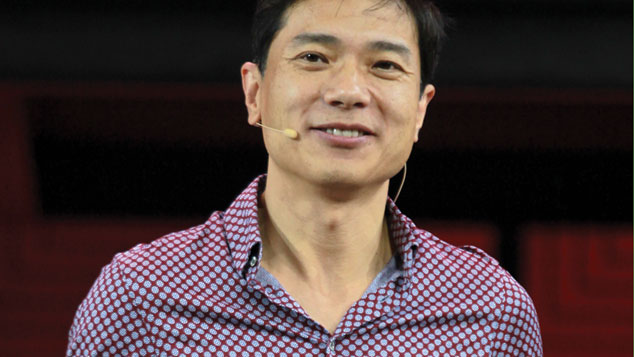

In 2000 there was just one dollar billionaire in mainland China, but the country’s economic growth has seen that number increase to several hundred today. Forbes puts the number at 319. Shanghai-based publisher Hurun says there are 594, more than the 535 in the US. A 2015 report from UBS and PwC found that China was creating a new dollar billionaire nearly every week in the first quarter of that year. Many come from humble backgrounds – Alibaba founder Jack Ma (net worth $30.3bn) is a former school teacher; Baidu co-founder Robin Li (pictured above – net worth $12.8bn) was born to factory workers. Hurun reports that China also boasts the largest number of female billionaires in the world with 56, more than half of the world’s total.

Why are some now under presssure?

Because of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. The government said in October last year that more than one million officials had been punished for corruption since 2013. Many of these were low-level bureaucrats, but the campaign has also targeted more senior figures. In 2015 alone corruption investigations were opened against 13 senior generals; deputy provincial governors and general managers at major state-owned enterprises such as China National Petroleum Corporation were also arrested or expelled from the party. When a senior official falls, it can spell disaster for those in business who have relied on these well-placed contacts.

Who has been affected?

Some of the cases have been dramatic. Former mining tycoon Liu Han, who was once worth $6bn and known for his love of casinos and luxury cars, was put to death in 2015 after being found guilty of running a “mafia-style” gang in Sichuan province. He was associated with Zhou Yongkang, the Politburo’s former security chief, who is the most senior official to be jailed for corruption. China has also seen a spate of “disappearances”, with billionaires and chief executives frequent targets. Guo Guangchang, self-styled as “China’s Warren Buffett” and head of Fosun, the country’s largest private conglomerate, went missing at the end of 2015 only to reappear a week later after “assisting in certain investigations”. Bloomberg reports that senior executives from at least 34 listed firms “disappeared” in 2015.

Can they flee abroad?

The wealthy have long been prepared to emigrate from China: a study by estate agent Knight Frank found that 76,200 Chinese millionaires left the country between 2003 and 2013, 15% of the total millionaire population. Many move funds by buying property and assets in the West. China is thought to have lost about $3.8trn to capital flight over the last decade, says Frank Gunter in Forbes, far outstripping the money that comes into the country through foreign direct investment. Hence Beijing has clamped down on overseas acquisitions by Chinese firms in a bid to limit outflows – and prevent embezzled funds from moving abroad.

Does this keep them safe?

Not necessarily. Billionaires such as Guo Wengui (see box) often leave the country when their government contacts are taken down by corruption investigations, but even this might not keep them from the reach of mainland authorities. Financier Xiao Jianhua, who is worth $6bn, was seized at the Hong Kong Four Seasons hotel on Chinese New Year’s Eve this year. The abduction came despite rules prohibiting the operation of mainland law enforcement agencies in the region and Xiao’s close ties to several family members of senior party officials.

Who may be in the firing line now?

The financial elite – in particular, the insurance industry, where a recent boom has enabled firms to “finance splashy foreign acquisitions and corporate raids on listed Chinese companies”, say Gabriel Wildau and Charles Clover in the Financial Times. Xiang Junbo, the head of the insurance regulator, has been arrested on suspicion of “severe disciplinary violations” (ie, corruption). And Anbang, an insurer that bought New York’s Waldorf Astoria hotel for $1.95bn in 2015, and Wu Xiaohui, the tycoon who controls it, are now in the spotlight. Recent deals have fallen through amid opposition from the authorities, while Caixin, a finance magazine, has published claims of irregularities at the group. Anbang is now threatening to sue Caixin and its editor-in-chief Hu Shuli.

Has the clampdown worked?

Xi’s anti-corruption drive has widespread public support in China, and nearly two-thirds of respondents to a Pew survey last autumn said they thought China’s corruption problem would improve over the next five years. However, many analysts see the campaign as a tool for Xi and his allies to consolidate power. Guo, who has become a vocal critic in exile, argues that “among the elite, the campaign touches only those who are already on the losing side of factional power struggles”, says Michael Forsythe in The

New York Times.

The most wanted man in China

Most Chinese billionaires who leave the country keep a low profile, but property tycoon Guo Wengui has created a public persona “more akin to a dissident Russian oligarch” since leaving two years ago, says Michael Forsythe in The New York Times. The 50-year-old came to prominence in 2014, when a corporate feud erupted over his attempts to acquire a stake in a major brokerage firm. Guo’s close ally Ma Jian was arrested for corruption in the wake of the failed deal and Guo fled the country. “Guo has been making serious accusations of corruption against China’s former and current officials,” says Zheping Huang on Bloomberg, including against Wang Qishan, China’s top graft-buster and widely considered to be the country’s second most powerful man. China asked Interpol to issue a “red notice” for Guo’s arrest last month, but did not specify the reason.