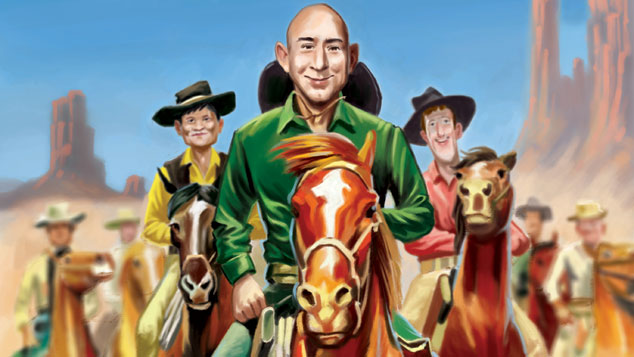

Amazon, Google and Facebook aren’t the only winners in ecommerce and online media – savvy investors should also buy China’s big four to maximise gains, says Rupert Foster.

Right now, two of the biggest industries in the world – retail and advertising – are being turned upside down by the internet. This process has been ongoing for more than a decade, and we’re now at a point where the biggest winners are becoming very clear. Yet although their dominance is only growing, there is still plenty more market share for these companies to grab. Put simply, as an investor, you can’t ignore these “Magnificent Seven” internet stocks. So who are they, and how can you invest in them?

Mention ecommerce, and most of us immediately think of Amazon (Nasdaq: AMZN). Small wonder. Last year, US consumers spent $12.6trn, up 2.6% on 2015. Amazon – which already accounts for 43% of US online sales – captured about 20% of that extra spending. That’s an incredible statistic. Yet in China – currently the world’s fastest-growing consumer market in absolute terms – more than half of the extra $700bn spent by Chinese consumers last year went to just one company, Alibaba (NYSE: BABA).

Alibaba already has a domestic market share of around 70%. Its smaller rival, meanwhile – JD.com (Nasdaq: JD) – captured 20% of that extra growth. Over the last five years, the share of consumption growth taken by Amazon, Alibaba and JD.com in their core markets has grown steadily – so they are becoming more, not less, dominant.

This trend is echoed in online media. All of the growth in the online advertising market so far this year has been taken by Alphabet (formerly known as Google – Nasdaq: GOOGL), Facebook (Nasdaq: FB), Alibaba, Tencent (HK: 0700) and Baidu (Nasdaq: BIDU). And with online advertising still only accounting for 40% of global advertising spending, there is plenty of room for growth.

TV is still the dominant advertising medium, but online players are breaching this “final frontier”, either via user-created TV (services such as YouTube or Facebook Live), or simply by offering traditional sports and soap operas. Facebook has started buying in sports events and episodic content in the same way as ITV and Sky have done for years. Facebook users can now watch TV through the social media site, rather than on the box in their living room.

There is also crossover between these two core sectors. In China, Alibaba not only dominates ecommerce, but is also the second-largest player in terms of search-engine revenues, after Baidu. If a Chinese person wants to buy an item, they go to one of Alibaba’s two websites – Taobao or Tmall – and enter the search term there.

Alibaba runs a pure marketplace website and so sells the search rankings to the highest bidder, just as Google does in the West. In effect, it’s an online shopping mall, with Alibaba as the mall owner – it takes no inventory risk, but instead gets a cut of every transaction conducted in the mall. (Amazon, by contrast, is a hybrid. It started as a pure ecommerce retailer – ie, it took inventory risk – but it now runs a shopping mall model as well.)

Building a walled garden

Alibaba is also the most advanced of any online business when it comes to spreading itself across many different sectors. The ideal for any internet giant is to keep customers inside a “walled garden”, to maximise their ability to sell them goods and services, and to sell their attention to advertisers. So a consumer might speak to her friends on your social media site, then buy her new phone on your shopping site, and pay for it with your payment service. This constant attention is valuable, and companies will offer decent freebies to attain it.

For example, Amazon tries to encourage customers to join its Prime service, which – in the UK – offers free, fast delivery of Amazon goods for £79 a year. Users who have Prime are more likely to use Amazon in the future, so as an incentive to sign up, you also get Amazon Video for free. This streaming service (providing films and TV over the internet) is not far off Netflix in terms of depth of content, and Netflix will cost you at least £72 a year in the UK.

But Alibaba could take this to new levels. Beyond ecommerce and search, it also owns Ant Financial (the leading financial technology business, which runs Alipay, the main online payment network); Youku (a streaming service); Didi (the leading taxi service); Ele.me (a takeaway service like Just Eat); and Alicloud, the leading cloud computing service. Alibaba also owns stakes in Weibo (China’s version of micro-blogging service Twitter); Paytm, India’s main online payment service; and in most of the largest independent logistics companies in China.

Alibaba plans to bring this dizzying array of businesses together into one offering in the next five years, giving it a big advantage in the fight to monopolise the eyeballs of Chinese consumers. It will face competition in each individual market. But the only other players who can hope to match it in terms of breadth are Tencent and Baidu.

Tencent is the social media champion in China. It owns Weixin (known as Wechat in the West). The social media site has 880 million users and, on average, each user spends an hour a day on it, messaging or chatting. This provides Tencent with a great online advertising business, but also a strong hold on the attention of many Chinese consumers. Tencent has almost as many other businesses as Alibaba as it seeks to maximise its own walled garden offering.

It’s also challenging Alibaba on its own core territory, ecommerce. Tencent owns a 20% stake in JD.com, the second-largest Chinese ecommerce player, but it is also using Weixin to aid ecommerce interaction directly. For example, many Western luxury brands have boosted their Chinese sales recently, simply by focusing more on Weixin links. This points to the focus for both Alibaba and Tencent over the next five years. They already have monopolistic or duopolistic control of their core markets – now it’s all about fighting for attention in the battle of the walled gardens.

For investors, China’s big online players provide an interesting test case for how their equivalents in the West might evolve. Chinese consumers are generally much more engaged online than those in the West. That’s mainly because China never had many strong offline businesses and brands, so it was easy for the likes of Alibaba and Tencent to conquer online retail because existing competition was so weak. The West, on the other hand, already had strong bricks-and-mortar retailers, popular consumer brands, and big publishers and broadcasters, all of whom have waged a fierce rearguard battle against the online onslaught. They are losing – but slowly.

This explains why the level of ecommerce penetration in China is double that of the US. For example, PayPal recently boasted that customers use its service three times a month on average. But in China, Tencent’s Tenpay and Alibaba’s Alipay are used more like 30 times a month on average – the Chinese are vastly more engaged with financial technology than we in the West are.

On the one hand that’s good news for the likes of PayPal, as it highlights the potential for growth over here. But on the other hand they also know that at some point Alipay and Tenpay will expand westwards and provide formidable competition. Indeed, it’s already happening – Ant Financial is currently buying Moneygram, a US payments business.

Great companies – but should you buy in?

It’s clear that these are good businesses in strong market positions. But they’ve also done very well in recent years. So are they still worth investing in? In my view, yes, very much so. Alibaba, Amazon, Baidu, Facebook, Google, JD.com and Tencent all generate plenty of free cash flow. Free cash-flow yields on these stocks range from 2.5%-3.7% (Amazon and JD.com are the least attractive, while Alibaba, Facebook and Tencent are the most). That may not sound appealing compared with the average of 4% for S&P 500 firms.

However, free cash flow is still growing rapidly, even as these companies are investing heavily in their businesses. For example, Facebook spent $4.4bn last year, and it expects that to grow by 30% a year for the foreseeable future; but it generated more than $10bn in free cash flow over the same period – and that looks likely to grow by about 35% a year. The average S&P 500 company, on the other hand, has average cash-flow growth of around 5%-10%. Similarly, if you look at price/earnings (p/e) ratios, these companies trade at premiums to the average – but they are generally cheap compared with their own growth rates.

The two main threats to the Magnificent Seven

So what are the risks? There are two big ones. In their core markets, the key risk is not competition, but governments and regulators. The European and UK authorities are ratcheting up pressure on Google and Facebook to monitor their sites for criminal content more effectively. Facebook will expand the Facebook police force by 3,000 people this year, to 7,500. This may sound a lot, but when a business has free cash flow of $10bn-plus a year, spending $500m a year on policing sounds cheap.

In the longer run, governments will have to make online businesses legally liable for all the content on their sites if they want them to be policed properly. Long term, that seems likely to happen but will be fiercely opposed – “Big Internet” is now the largest (by dollar amount) political lobby group in Washington and Strasbourg. And while the European authorities – possibly because the top players are all American or Chinese – are more keen to tackle policing, the US government shows little interest. So this risk can be largely discounted for the next three to five years.

The second big risk is the battle of the walled gardens we discussed above. This will pull in the entire Magnificent Seven, of course, but also the two largest legacy businesses in the world (also now the richest cash cows in the world) – Apple and Microsoft. Other bit-part players will include Netflix and Tesla, along with content providers such as Disney, and distributors like Comcast. The first key battleground is likely to be content provision, with all players spending fortunes on new content. This will continue to drive content producers to new valuation highs over the next few years.

Future battles look set to be fought over artificial intelligence, and control of the “car experience”, as we enter the era of the driverless car. These nine businesses (including Apple and Microsoft) have dominated artificial intelligence research for years. This will distance them from other competitors, but it’s unlikely to provide a killer advantage in their battle with each other.

The battle for the car experience may prove more fertile. The average American still spends 47 minutes a day in a car. When that car has driverless capabilities, all nine players will want to be the ones to fill that new chunk of spare time. The war will be ferocious, and it is too early to tell who will be the winner. That said, there is nothing in the valuation of these businesses for this new area, so we can sit back and enjoy the ride. We look at how to invest in more detail below.

One investment trust to own them all

In the short run all of the shares mentioned above have performed very well, as the bull market heads into its ninth year and investors desperately search for predictable, strong growth. Any correction is likely to affect these names more than others because of the sheer extent of their rise and the number of short-term holders. But for a long-term investor, this should present a wonderful opportunity to pick up a collection of seven magnificent businesses.

However, you don’t have to invest in them individually. An easier way for long-term investors and those who would prefer to drip-feed regular amounts into these stocks (and other promising players in similar sectors) is to buy the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust (LSE: SMT). Scottish Mortgage has long been one of MoneyWeek’s favourite investment trusts.

While managers James Anderson and Tom Slater don’t reflect our value investing tendencies (high-tech stocks very rarely trade at “value” levels), they are high-conviction, long-term investors and that conviction has paid off handsomely – the share price has more than trebled in the past five years (its benchmark has doubled).

The top holding is Amazon, with Tencent, Alibaba, Facebook, Baidu and Alphabet also in the top ten (the top ten as a whole accounts for more than half the value of the overall portfolio). Other tech-sector holdings include gene-sequencing group Illumina and electric-car specialist Tesla. The trust trades at a premium to net asset value of around 3%. We’d rather buy at a discount (when the share price is cheaper than the underlying portfolio) if possible, but barring a crash, don’t expect to get much better than a 2% discount on this trust.