Turkey is heading for default, says Jonathan Compton, and the resulting global domino effect should not be underestimated. Investors should stand clear.

Emerging-market stocks have rallied this year, as US President Donald Trump’s protectionist bark turned out to be worse than his bite (for now). But investors should be wary of getting over-enthusiastic. Major sovereign defaults in emerging markets are as predictable as the seasons – they recur about every two decades, when the previous generation of participants has retired. That means we’re overdue one. But where will it begin?

The last two collapses started where they were least expected – in Malaysia (in 1997) and Mexico (1982). Each had a domino effect into other, seemingly unrelated countries. So who will it be this time? Turkey. I expect the country to default on its sovereign debt by the end of next year. And while foreign equity exposure to Turkey is tiny, the ricochet into more popular emerging markets – as well as into some developed market financial systems – will be significant.

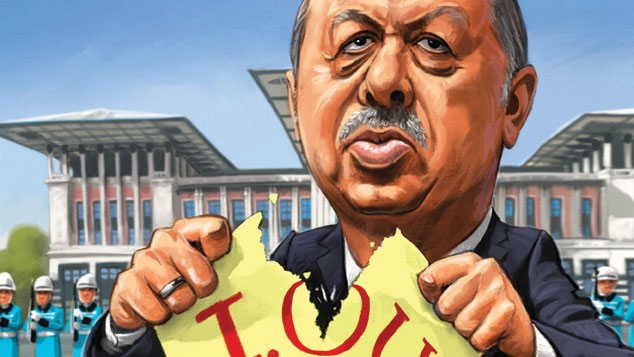

Why am I certain that Turkey will soon default? Because President (and would-be Sultan) Recep Tayyip Erdogan has said so. His consistent theme has been: “We are heirs to the Ottoman Empire, which had been exploited since 1854 by [foreign] banks, bankers and loan sharks”; and “I can’t consent to wasting my people’s rights through high real interest rates”; or “all loans, now and in future, should be interest-free”. Investors refuse to listen. But they should.

As a member of the G20 group of wealthy countries, Turkey matters, especially given its geographical location and that, for the last 40 years, its large, relatively stable economy has been a significant stabiliser in a turbulent region. Yet Turkey is rapidly sinking into ever-darker waters, threatening contagion into other emerging markets.

From market darling to pariah

Turkey became a market darling in the late 1990s, when Erdogan was serving as a successful mayor of Istanbul. After founding his Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2001, he led it to general-election victories in 2002, 2007 and 2011 before standing down, to be elected president in 2014.

His success arose from large public-sector infrastructure projects (such as the third bridge over the Bosphorus), which Turkey needed. These were funded by foreign and local debt. Growth improved steadily and over the last 20 years the stockmarket has risen tenfold (in local currency terms). Meanwhile, Turkey’s perennial twin problems of high inflation and a rapidly depreciating currency eased. Perhaps most importantly, Erdogan held out hope of an end to the long-running civil war in the Kurd-dominated east of the country.

Erdogan depicted himself as a free-market conservative-liberal (self-branded as “Erdoganism”), and the world was eager to believe, despite thumping hints to the contrary. The European Union (EU) and America needed a poster boy to prove that a major Islamic nation could be secular and outward-looking, with a functioning democracy, real human rights, and a free judiciary and press. Nato wanted a bastion on its southeastern flank as a counterweight to largely hostile regional dictators and to Russia. For a while, it worked.

But often seemingly trivial events give hints of wider changes. In 2007, as prime minister, Erdogan complained of cockroaches in his office. This resulted in the colossal new Ak Saray palace (now for the president’s exclusive use; the current prime minister still has the cockroaches). The floor area of his new palace is said to be 40 times that of the White House in Washington; estimates of costs vary from $600m to $1bn – and it’s still incomplete. Giant personal palaces are always a bad sign. Worse is the symbolism.

The palace was deliberately placed in the centre of the Atatürk Forest Farm. The forest, in the Turkish capital, Ankara, was given to the nation by Kemal Atatürk, the father of a modern, outward-looking, secular, and progressive Turkey. It was the most legally protected, and perhaps revered, plot in the country. Yet despite the highest court declaring the construction illegal, and ruling that it had to come down, Erdogan took no notice.

After his murky 2011 election victory, Erdogan accelerated his policy of ending Atatürk’s legacy. He worked to make the country purer and more Islamic, moving unelected placemen into positions of power, irrespective of the legalities or their ability. Corruption soared. His family and inner circle have allegedly supported Islamic State by illegally shipping and selling oil from its fields in Syria and Iraq (they deny these claims). The army, historically the upholder of the Atatürk tradition, attempted a coup in July 2016.

This collapsed, in part because senior officers had been supplanted by placemen, but more because even Erdogan’s opponents put the importance of democracy above his increasingly unpopular policies. In the post-coup reaction, more than 4,000 judges and prosecutors have been sacked along with 10,000 academics; opponents in the press, civil service and police have been cleansed; more than 100,000 ordinary citizens were detained. The speed and scale of the purge has left the population cowed, and Erdogan continuously discovers new foreign plots.

The final nail in Atatürk’s legacy was the referendum in April. This sought to abolish the role of prime minister, de-claw parliament and create an all-powerful executive presidency led by Erdogan. Despite controlling almost all the media, locking up opponents, and banning their rallies, Erdogan only squeaked home by 51%-49%, largely because all invalid ballots were ascribed to him. Such tactics will ensure another “victory” in the 2019 parliamentary and presidential elections, which means he could rule unopposed until at least 2029. In just 15 years he has moved from being a dynamic people’s democrat to a paranoid dictator.

The consequences for investors

Turkey’s stockmarket is unimportant, at less than 0.3% of world market capitalisation, so why should investors worry? The answer is because of the potential impact on bond markets. Annual spreadsheet snapshots to assess country risk give a false reading. Even late in 2016, Turkey’s numbers looked reasonable. The government debt-to-GDP ratio had fallen to a comfortable 29% (most developed countries are at 80%-plus).

Inflation was a fraction of 20th-century averages; growth chugged along at 2%-4% a year; foreign-exchange reserves had risen sevenfold since 1995 to $13bn; the budget deficit was very low at 1% of GDP and the 3.8% current-account deficit was easily covered by foreign indirect investment, chasing Turkey’s low-cost labour and high productivity. In short, a situation healthy enough for bond analysts and rating agencies to ascribe Turkey a vital sovereign-grade rating.

But such analysis ignores all-important human factors. Governments often turn loopy at short notice, but markets are slow to catch up. Erdogan wants to renegotiate the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which delineated modern Turkey’s frontiers. Government-sponsored maps indicate a vague redrawing to recover the lost lands of the Ottomans (to whose once-magnificent empire Erdogan longingly refers). This requires the annexation of parts of Greece, Syria and Iraq, and perhaps parts of the Caucasus. (Turkey remains in defiant denial over its attempted genocide of the Armenians a century ago.)

The Ottoman theme runs through Erdogan’s policies like the words in a stick of rock. As the Arab Spring unfolded, he emphasised Turkey’s historic Ottoman role, not just with immediate neighbours but in Egypt, Libya and beyond. He excoriated a hugely popular TV series (400 million viewers across the Middle East) on Suleiman the Magnificent, the longest-reigning Ottoman sultan (1520-1566), because it showed him to like fiery cocktails and hotter redheads; Erdogan insisted it should focus on his manly, nationalistic virtues and victories.

More important are Turkey’s weaknesses. The snapshot ignores some rapidly deteriorating trends. Tourism is vital to the economy, but has shrunk by a quarter as a result of the coup, referendum, riots, resurgent demands by the Kurdish minority and the conflict in Syria. Overseas investors have also been put off, so foreign direct investment is tumbling. Inflation and unemployment are both at 12% and rising as the currency weakens. Domestic investors are switching into dollars and gold. Erdogan’s response has been a mixture of patriotic appeals to swap these assets into Turkish lira while trying to coerce the central and commercial banks to offer negative, thus loss-making, real (after-inflation) interest rates.

The cracks in the economy

Such a futile reaction reveals the real problem – the level of foreign-currency borrowing in Turkey’s private sector is out of control. This is common to many developing countries. Their governments have learned the perils of excessive borrowing overseas, but their private sectors have raced abroad to exploit the huge gap between local and foreign interest rates – 7% or more in Turkey.

Unfortunately, this ignores the repayment crunch if the local currency weakens. Turkey’s corporates are hugely over-exposed; over the last decade, their borrowing in foreign currencies has risen at the fastest rate of any emerging economy save China. The total dwarfs government debt.

A significant proportion of new loans are used solely to pay interest, thus increasing the debt burden and making the hole of mismatched foreign debt against local-currency earnings ever deeper. The crisis has not yet broken because until last year the amount due for repayment was small. From now on, it rises steadily. It is simply a matter of time. Meanwhile, analysts are once again missing the fact that although the government (or Erdogan and his court) may have the ability to repay its debt, it has no intention of doing so.

Twenty years ago there was almost no foreign-currency borrowing by local companies in emerging markets. Now it is vastly greater than borrowing by their governments. Yet these debt markets remain highly illiquid; worse, many funds own this debt through even more illiquid derivatives. As Turkey’s private sector fails to repay, the spotlight will fall on the other countries with similar private-sector foreign-currency debt, setting off a chain reaction. Many funds will suspend redemptions, thus increasing investor alarm, into Asia and elsewhere.

Corporate Turkey’s main lenders are France, Italy and some Spanish banks. It’s not in their prices at all. How can I be so certain about a Turkish default? Because, as I noted above, Erdogan says so. But it also comes from studies by the doyens of default, Professors Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff. They conclude that one of the most infallible guides is the historical record. Between 1876 and 1982, Turkey defaulted six times. Betting against a relapse seems foolhardy.

Four defence stocks to buy

Turkey has many decent manufacturing businesses, but when the debt market implodes, the stockmarket will follow. So I won’t tip them. Instead, I’ll revisit a theme I first highlighted 18 months ago – defence stocks. Political instability is growing across the old world and defence budgets are rising, and turmoil in emerging markets would only accelerate this trend. As a result, the following companies should continue to do well. (Disclosure: I own the first three of these tips in my personal portfolio.)

The best performer has been BAE Systems (LSE: BA). Results for last year show 13% growth in underlying profit and a £6bn rise in its order backlog to £42bn. All five major divisions performed well. BAE’s dependence on the US and Saudi Arabia (35% and 20% of sales respectively) is a minor negative, but that’s where the orders are. On a forward multiple of 13 times and a yield of 3.3%, it remains cheap.

I also remain keen on the more UK-dependent Babcock International (LSE: BAB). Its share-price performance has been poor due to a variety of self-inflicted wounds, but its defence arm accounts for 40% of revenue and results show steady growth. In its other sectors, such as energy, support services and managing much of the Royal Navy’s infrastructure, the picture is also improving. On a prospective multiple of 11 times (50% below its long-term average), the market still distrusts management. I think it’s wrong.

New to this group is Rolls-Royce (LSE: RR), with its superb position in commercial aero engines and power systems. Although the civil sector is by far the larger, it is also heavily involved in developing engines for military aircraft, helicopters and frigates. A one-time market darling and “safe blue-chip”, it rightly fell from grace at the end of 2013 as a result of sclerotic management, missed profit forecasts, cost over-runs and corruption probes. The share price bottomed out at the start of last year, following the appointment of Warren East in 2015, who previously built up the highly successful ARM Holdings. His restructuring programme is well under way and a return to profitability is likely by the end of this year.

I would still recommend my best foreign pick, which was Raytheon (NYSE: RTN). It makes and operates “integrated defence systems”. In lay terms, it makes a range of missiles and rockets, and provides logistical support. From the Korean peninsula to the Middle East and at home, demand is going one way, yet – surprisingly at 20 times earnings and a 2% yield – it remains cheap against the sector and against its own history.