The S&P 500 Information Technology index hit an all-time high last week, surpassing its previous record set at the height of the dotcom bubble. The index, which tracks the performance of large-cap US tech firms such as Facebook, Microsoft and Alphabet, the parent of Google, edged above the peak of 988.49 achieved on 27 March 2000. The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite, which passed its bubble-era peak more than two years ago, also reached new highs earlier this week ahead of forthcoming earnings reports from several tech giants. US tech stocks have outperformed the broader market so far this year, gaining 23% compared with the S&P 500’s 10% rise.

“The S&P tech sector has been slower to reclaim record levels than the Nasdaq in part because it is missing some of the Nasdaq’s biggest gainers,” say Amrith Ramkumar and Ben Eisen in The Wall Street Journal. S&P counts Netflix and Amazon in its consumer-discretionary sector rather than tech, despite their online operations.

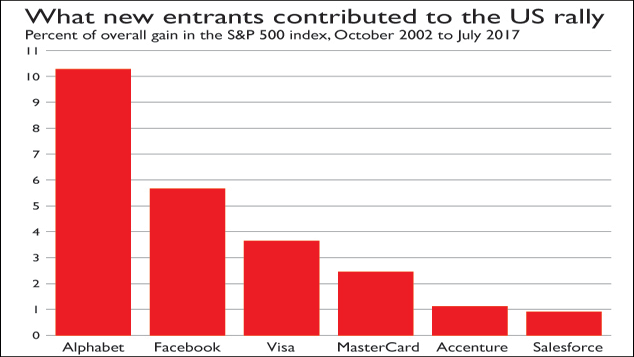

What’s more, to call this a recovery is misleading, says the Financial Times’ Lex column. Few of the survivors of the original dotcom bust have contributed to the index’s new peak. “The heavy lifting has been done by new entrants.” More than 40% of the rebound since the 2002 lows comes from Alphabet and Facebook alone, neither of which were even listed in 2000.

What has not changed from those days, of course, is the question of whether this is a boom or another bubble. Investors “are quick to note that there are major differences between technology stocks now and in the year 2000”, say Ramkumar and Eisen. The S&P 500 tech sector is trading on a price/earnings (p/e) ratio of around 23 at present. That’s higher than the 22 times earnings at which the wider S&P 500 benchmark is trading, but is far below the valuations seen at the height of the bubble, when the p/e ratio peaked at 70.

Importantly, the tech sector is much more profitable than it was during the dotcom era, James Tierney of asset manager AllianceBernstein tells the FT. “Ultimately stock prices follow earnings. Growth is accelerating not decelerating, so you need to be there.” Yes, “there are a few companies like Netflix and Amazon with nosebleed valuations – but most are not”.

Still, those who think the market is wiser this time around should remember that the biggest tech groups in 2000 were highly profitable as well, says Lex. “Oracle and Microsoft in 2000 performed better than Alphabet and Apple (and Microsoft) in 2017, measured by gross profits to total assets.” Even strong and profitable businesses can see future expectations rapidly reset. “Current profits are little insulation against a market correction.”

The rise of “apocalypse insurance”

“If bonds are the old world’s safe haven, bitcoin is the millennial generation’s apocalypse insurance,” says Lionel Laurent on Bloomberg Gadfly. A decade of “ultra-cheap central-bank cash” has sent money flooding into crypto-currencies: digital currencies that are “marketed as a direct expression of opposition to central-bank and government policy”.

There have been “dizzying rises” in the prices of leading crypto-currencies such as bitcoin and ether, up more than 130% and 2,300% respectively this year, says Timur Onder on Breakingviews. However, the most dramatic development has been the raft of tech start-ups bypassing traditional markets to conduct their fundraising in the currencies. “Initial coin offerings, or ICOs, have taken off, raising $1.3bn so far in 2017.”

ICOs are “a bit like a cross between crowdfunding and issuing non-voting shares”, with investors given tokens that they then hold “in the hope that they will rise in value”. Yet this unregulated fundraising technique, often based on little more than a vague “white paper” issued by the start-up, looks a “risky recipe”.

“The question is whether this fad represents a legitimate mechanism for helping ventures access funding markets or is just another bubble in the making,” says Izabella Kaminska in the Financial Times. Right now, ICOs look like the latest innovation in shadow banking, where “minimal regulatory constraints” and “excessive risk taking” spelled disaster for the sector during the financial crisis. Such systems are prone to collapse because “the epic valuations being bandied about are liquidity dependent” – there is no central bank to step in as a lender of last resort when markets seize up. “Do investors realise the risks they have taken on?”