The big question this week is: where to next for the US dollar? If you are at all interested in where asset prices are heading next, then you have to pay attention to the price of the world’s reserve currency. It affects everything.

Broadly speaking, when the dollar gets more expensive, money around the world gets tighter. When the dollar gets cheaper, money loosens. That’s because – on a very simple level – everyone needs dollars. So when dollars are cheap and easy to get hold of, monetary policy is loosened.

So far this year, the dollar has been tanking. And that’s been bullish for most assets – from emerging markets to US stocks to commodities. However, as we can see from the “charts that matter” below, the dollar index seems to be nearing quite a critical technical juncture. And lots of people are positioning themselves for a bounce.

Is the dollar going to hit a bottom and bounce, or does it have further to fall?

Well, this week I’ve been reading an interesting piece from a group called Crossborder Capital that I thought I’d share with you. Crossborder tracks money flows across the globe. The basic idea is that what ultimately matters to markets – in terms of asset prices – is where the money flows (we’ll have more details on their thinking in an article in MoneyWeek magazine in the next couple of weeks, but that’s the simple version).

When it comes to big-picture money flows, we’re used to thinking about central banks and all their money printing. That’s why the idea of “quantitative tightening” (QT) is sending mild jitters down the collective market spine.

Central banks have been printing money and keeping the show on the road ever since 2009. The question “what happens if they stop?” is what’s keeping everyone awake at night.

It’s certainly an issue to be alert to, says the team at Crossborder. However, there’s another, potentially even bigger issue, that investors aren’t paying such close attention to. That’s the question of cross-border capital flows – the tide of money flowing from one country to another.

“$3.5 trillion of net capital has left the eurozone and China alone since 2011”, notes Crossborder. That money flowed into US Treasuries (US government debt), partly as a result of investors hunting for “safe” assets.

Now, $3.5trn is a very significant sum of money. In total (so we’re not just talking about the Federal Reserve), central banks added $5.5trn to markets since 2008. So cross-border capital flows are a serious market-moving force.

And the thing is, a lot of that $3.5trn is now “heading back home” as risk appetite in Europe improves, and China cracks down on capital flight. So what does that mean for the dollar and US assets?

The surprising truth about QE and bond yields

First a bit of background. Crossborder Capital argues that quantitative easing (QE) actually pushed the yield on US government debt higher.

That might seem counter-intuitive. If the US central bank was printing loads of money to pump into bond markets, then why would bond prices fall? (Yields move in the opposite direction to prices.)

Yet it’s true. As James Ferguson of MacroStrategy used to always point out to us at MoneyWeek, US Treasury yields actually rose during periods of QE and then fell during periods when the Fed decided to stop printing.

The market assumed that all the money printing would prop up asset prices and eventually trigger inflation. And when the Fed stopped printing, the market worried that everything was going to go horribly wrong, deflation would return, and so demand for Treasuries shot up. In effect, the Fed chased investors out of Treasuries almost as quickly as it was buying into them.

So what has in fact helped to suppress Treasury prices, argues Crossborder, is not so much buying by the Fed, as capital inflows from jittery overseas investors. “Chinese flight capital that fled through the 2014-16 period, combined with the spillover of eurozone liquidity from the European Central Bank’s huge QE programme, largely flowed into US Treasuries.”

So let’s just summarise. You’ve got the Fed printing money, and driving US Treasury yields higher. But nervous Chinese and European investors are buying, driving yields lower. Both of those forces are now reversing. So QT – argues Crossborder – should drive Treasury yields down. But reversing capital flows – foreigners selling US Treasuries – should drive yields higher.

What’s the impact? I’ll cut to the chase and skip the maths.

Crossborder reckons that in this tug of war, the foreign investors win out. In other words, “the negative impact on yields from less QE is likely to be more than offset by the positive impact from exiting capital flows. In addition, as capital quits the US markets, the US dollar should also weaken.”

In other words, although you’d normally expect QT to drive the dollar higher, in this case, capital flows are likely to have a bigger impact. As a result, Crossborder expects US ten-year Treasury yields to hit 3.5%, and the US dollar to weaken by 5%-10%, “notably against the euro”.

It’s an interesting and logical argument, and not a particularly mainstream one, so I’m inclined to like it. The one query I’d have is whether the Fed is particularly planning to do any QT, given the relatively weak data on the US economy in the last few days. But I suppose that would only make the case for a weaker dollar even stronger.

The charts that matter

The weak dollar narrative has continued apace this week. Part of the negativity on the dollar is about politics and the ever-erratic Donald Trump and team. But it’s also about the Fed sounding as if it’s in no great hurry to raise rates or tighten up its balance sheet.

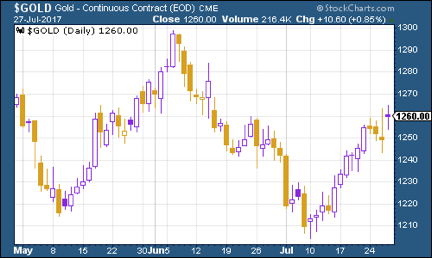

Gold

All of this has helped gold to continue to rebound nicely. It was back above $1,260 an ounce, capping a fairly consistent fortnight for.

On a week-to-week basis, I’m not too concerned about what happens to gold. It’s something I’ll be hanging onto in my portfolio as insurance, in any case. But if you do think that the dollar is going to continue lower, then gold is likely to continue to do well.

(Gold: three months)

(Gold: ten years)

US dollar index

The US dollar index kept sliding this week. It’s the steepest decline seen in six years, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Now, I’m not a chartist, but I do respect charts (even if you think it’s all nonsense – which I don’t – enough people pay attention to them to have at least some relevance). If you look at the ten-year chart below, the US dollar is very close to a key area – around the 92.50 mark. If it breaks down through that, there’s not much in the way of support to stop it falling a lot further.

(DXY: three months)

(DXY: ten years)

Ten-year US Treasury bonds

These are drifting higher again, but there’s no clear conviction either way. The market, in effect, is still struggling to believe that inflation is heading a lot higher any time soon.

(Ten-year US Treasury: three months)

(Ten-year US Treasury: ten years)

Copper

Copper has been storming ahead this week. The weaker dollar has helped, but a strong showing for the Chinese economy in the second quarter has probably been more important.

(Copper: three months)

(Copper: ten years)

Bitcoin

Bitcoin has had another reasonably calm week. A split in the cryptocurrency doesn’t seem to be fazing its fans and nor does the striking scepticism displayed towards bitcoin and its fellow digital currencies by Oaktree Capital’s Howard Marks this week.

US jobless claims data

David Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff reckons this is a valuable leading indicator. When the figure hits a “cyclical trough” (as measured by the four-week moving average), a stockmarket peak is not far behind, and a recession follows about a year later.

This week, US jobless claims came in at 244,000. The four-week moving average edged higher to the same number 244,000, having hit its lowest level of the year on May 20th.

If that holds as the cyclical trough, then if Rosenberg is right (and to be fair, it’s a small data set) we might be looking at a stockmarket peak later this year – but it looks quite possible that the numbers could get even lower.

Oil price

Chart number seven is the oil price (as measured by Brent crude, the international/European benchmark). Oil has continued to rally this week, breaking through $50 a barrel.

Overall it was a pretty bullish week for oil – US crude stockpiles fell, and Saudi Arabia talked about cutting production. The talk might be of replacing petrol motors with electric cars, but it seems that 2040 is too far away to worry oil traders right now.

(Brent crude oil: three months)

(Brent crude oil: three years)

Amazon

The tech sector behemoth and destroyer of industries took a hit this week after results showed what they always show – that profits are smaller than expected, because Amazon is all about the investment.

(Amazon: three months)

(Amazon: one year)

At some point, the market will no longer be willing to fund a business model that’s predicated on “jam tomorrow”. But for as long as it is, the rest of us can sit back and enjoy the disinflationary consequences (as consumers) and fear the consequences for labour (as workers).