There’s a rule of thumb about people in powerful positions that I’ve always found quite useful.

For chief executives or national leaders, ten years is pretty much the sell-by date. By that point, they’ve either burnt out or they are losing their focus and embarking on vanity projects.

Margaret Thatcher (11 years). Tony Blair (ten years). Sir Terry Leahy stayed at Tesco too long (14 years, took his eye off the ball in the UK amid dreams of global empire building). Angela Merkel (12 years and counting, and clearly sick of it).

It’s why I think that on balance, the Americans have got it right with their idea of fixed presidential terms. Sure, you have the “lame duck” problem, but at least everyone knows what to expect and can plan accordingly.

Why am I sharing this with you this morning?

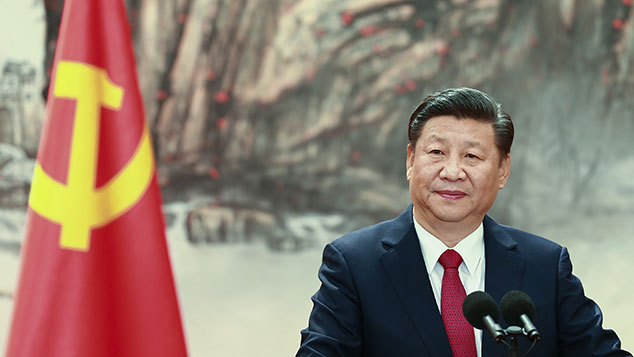

Because China, sadly, has just succumbed to the inevitable. The guy in charge has decided – against virtually every shred of evidence from history – that things would be better if he could always remain in charge.

Xi Jinping has no sell-by date, it appears…

Power needs a sell-by date – because eventually it goes rotten

That rule of thumb I mentioned above isn’t something I just pulled out of my hat, by the way. One 2013 study from the University of Texas (How Does CEO Tenure Matter? By Xueming Luo, Vamsi K Manuri and Michelle Andrews) suggested that roughly five years is the ideal time for a CEO to stay in power. Other, earlier research is a little more forgiving, suggesting that eight to ten years is about right.

But whatever the specifics, more than a decade is definitely cause for stakeholders – be they voters or shareholders – to start asking questions. Jack Welch was chairman and CEO of GE for 20 years. That says it all.

And if the boss decides that he wants to stay in charge for life? You shouldn’t need me to tell you that this is a bad sign.

Unfortunately, that’s what has just happened in China. Chinese president Xi Jinping has announced that China’s constitution will be revised to eliminate the current two-term limit on the presidency. It means that Xi could stay in charge after 2023, when his current five-year term runs out.

It still has to be voted on at the National People’s Congress, but it’ll happen.

The term limit was introduced in the 1982 by the reforming Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping. As Julian Evans-Pritchard and Mark Williams of Capital Economics put it, the goal was “to prevent any future leader becoming as dominant as Mao had been”.

So much for that. As Eoin Treacy puts it on FullerTreacyMoney.com, China has now moved from “single-party government to single-person government”.

Now, to be fair, as Capital Economics points out, “it is possible to make a case that these developments could be good for the economy”. And enamoured China-watchers will probably try to do so. If you have a strong man at the helm, after all, it’s easier to push through all those tough reforms that have previously faltered due to vested interests or factional infighting.

Or at least, that’s the Pollyanna argument.

But as Capital then notes: “we are sceptical that Xi will act in this way”. Put simply, Xi wants to get the benefits that go with a more free economy, but he also wants to concentrate power in his own hands. And you can’t have both of those things.

Indeed, “if anything, Xi’s major economic policy goal seems to be shoring up the role of the state sector so as to ensure that the leadership still has significant say over economic outcomes. Of course, Xi could change course if growth disappointed in future. But it seems just as likely that Xi would double-down on state control, making matters worse.”

If you’re still not convinced, just look at the way the China Daily presented the news. The change has been “necessitated by the need to perfect the party and the state leadership system”.

How depressing. And all of this is happening at a time when China – via the marvel technologies of social media and digital payment systems – is building the biggest, most intrusive system for social control ever devised. In effect, your ability to access money and be part of the state will be based on your status as a “good citizen”. (This – perhaps somewhat optimistic – MoneyWeek cover story from a few weeks ago only gives an outline of the system, but it’s terrifying enough as it is).

What this means for investing in China

What does this mean for investing in China?

Markets have proved pretty indifferent. Indeed, the stockmarket in Hong Kong bounced strongly (although that was in line with other global markets). But markets don’t tend to react quickly to these things – they are quite short-termist. And they also tend to err on the “glass half-full” side.

But in the long run, it means that investing in China has become riskier. China was on a trajectory towards better things in the early 2000s. It was becoming more open, and it was becoming more integrated with the rest of the world.

But things have changed. That’s not just down to China. It’s another symptom of the end of “Pax Americana”. You move into a multipolar world, and countries can’t help but jockey for position. It’s unfortunate, but it’s the way it works. It’s another long-term cycle – we’ve had a period of globalisation, now we have the backlash.

Overall, all of this means that China deserves to be a cheaper market. I’d be wary of investing in the big Chinese tech stocks too. At the end of the day, an equity stake is only as good as the property rights that underpin it, and allow you to lay claim to ownership. Good luck enforcing those if push came to shove.