Light on news, heavy on insults – why did the fired FBI director write his book? Emily Hohler reports.

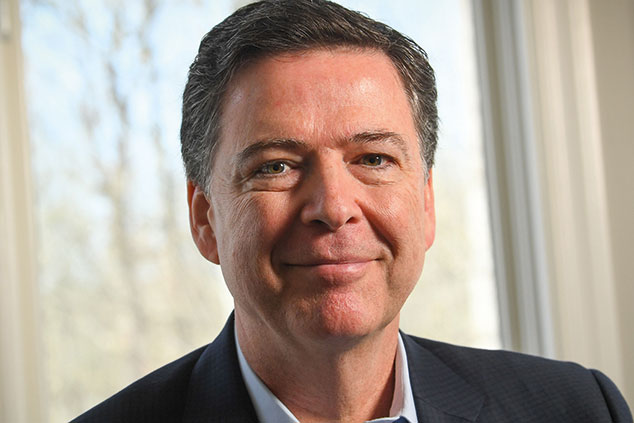

When Donald Trump fired James Comey as director of the FBI last May, Comey didn’t bow out of the public eye, says Jacey Fortin in The New York Times. “Far from it.” His memoir, A Higher Loyalty, was published this week and a long-awaited TV interview with George Stephanopoulos aired on ABC News on Sunday night. In it, Comey called Trump a serial liar who treated women like “meat” and described him as “morally unfit to be president”. Trump, for his part, has spent days waging a “ferocious counterattack”, branding Comey a “slimeball” and liar, suggesting he should be jailed for leaking classified information and lying to Congress.

Savour or villain?

“What, ultimately, are we supposed to make of Comey?” asks David Leonhardt in The New York Times. He may be the “most significant supporting player of the Trump era”, with a reputation that has “whipsawed” from saviour to villain. To be fair to Comey, he has “never been a partisan” and spent a “long career” at the Justice Department “upholding the rule of law without fear or favour”. But genuine as Comey’s “independence and integrity were, they also became part of a persona that he cultivated and relished” and this helps to explain his “great mistake”. Comey headed the FBI during the 2016 investigation into Hillary Clinton’s private email server. He decided she had done nothing to warrant criminal charges and knew Republicans would “blast him as a coward who was trying to curry favour with the likely future president”. So he went public with his explanation, while criticising her “harshly”.

Then, just days before the election, and against department policy, he released an update and said he was reopening the case. As he explained to Stephanopoulos, this decision was influenced by his certainty that Clinton was going to win, says Clare Foran on CNN. He thought that by failing to come clean, he would tarnish both the FBI and the presidential election, rendering Hillary Clinton’s presidency illegitimate. He was also, “not incidentally, going to protect his own fearless image”, notes Leonhardt. The fact is, “when doing the right thing meant staying quiet and taking some lumps, Comey chose not to”.

Comey’s real purpose

It is hard to work out who Comey’s book is aimed at, says Rob Crilly in The Daily Telegraph. There is a great deal of “character assassination”, but surely everyone has made up their own mind about Trump. By way of revelations – proof that the Trump campaign colluded with Russia or that the president tried to obstruct justice – there is little.

The main purpose of this book may be to help rebuild Comey’s reputation and atone for a “mistake that he believes put the boorish billionaire in power”, says Crilly. In that case, the “personal potshots” – at Trump’s “orange” skin, his too-long ties – may undermine his case, say Julie Hirschfield Davis and Jonathan Martin in The New York Times. They make him look petty and have surprised those who thought of Comey as “relatively sober and serious”.

Former FBI colleagues have accused him of “damaging” the agency’s reputation and “playing a dangerous game”, adds Joanna Walters in The Guardian. Having used both the book and TV interview to portray himself as the “defender of truth” and “paragon of intergrity”, Comey has “drenched the public discourse with the stink of sanctimony”, says Jack Shafer in Politico. You’d have thought someone with his familiarity with legal discourse would have a better idea of how his message would land. “When your 304-page book and marathon interviews produce sympathy for Trump – even a dollop of sympathy – you’re doing it wrong.”

The last days of the Wild West for tech

Mark Zuckerberg’s two-day Congressional testimony last week “failed to restore trust” in Facebook’s privacy policies, says Hannah Kuchler in the Financial Times. According to data from researcher Ponemon, confidence “collapsed” from 79% in 2017 to 27% this March, after revelations that a third-party app had given data on millions of users to Cambridge Analytica, a research firm working for Donald Trump’s campaign. Recent measures to restrict data access had been playing well, but Zuckerberg’s grilling appears to have reversed those gains.

This isn’t surprising, say Barbara Ortutay and Michael Liedtke in The Washington Post. The Facebook CEO was “unable to offer clear explanations or specific answers” to many questions, particularly those relating to how much personal data Facebook “vacuums up” from its users. It’s not just its users, says Matthew Field in The Daily Telegraph. The firm has information on many non-users, gleaned by scraping data from users’ lists of contacts.

The problem with Zuckerberg’s “marathon testimony” was not just the “technological illiteracy” of those doing the questioning, but the “lack of political will” and reluctance to “identify the problems”, says Kevin Roose in The New York Times. Lawmakers need to work out, specifically, what they think is wrong with Facebook and either tackle each issue or “spearhead an effort to break it up”. We’ll get there eventually, says John Steele Gordon in The Wall Street Journal. Whenever a “major new force” enters the arena, vast fortunes are created by entrepreneurs exploiting “new, largely unregulated economic niches”. A “new corpus of laws, regulations and commercial norms” subsequently needs to be developed in order to protect the public interest. “The Wild West days of Silicon Valley are coming to an end”, just as they ended for the 19th-century robber barons.