The Windrush fiasco claims the home secretary. The prime minister may be next. Emily Hohler reports.

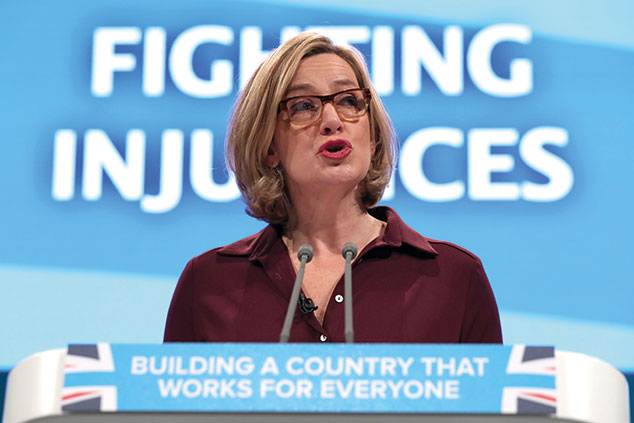

The resignation of Home Secretary Amber Rudd has pitched Prime Minister Theresa May’s “ill-starred government into yet another crisis”, says The Economist. It’s the fifth resignation of a cabinet minister in six months: more than a fifth of May’s second cabinet have quit their posts since last June. That is “quite a turnover”. Rudd’s resignation has given May several “new potential headaches”, says the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg.

It makes the government look weak just before Thursday’s local elections; Rudd was a “vigorous Remainer whose voice gave ballast to that side of the argument at the top table” (May’s ministerial committee on Brexit is split 5:5, with May holding the casting vote); and the Windrush “fiasco” may now be aimed more “sharply” at May herself. She is under fire, says James Blitz in the Financial Times, for having been the “true author” of the “hostile environment” that led to the Windrush debacle.

A government of ennui and drift

May’s opponents cannot “know how right they are” when they say that her Home Office tenure is “returning to dog her”, says Janan Ganesh in the Financial Times. The Home Office is “life and death work”, dealing with terror, illegal immigration and crime, but it is “inadequate preparation for Downing Street”. In her six years there, May “never had to create, only enforce”. There have been “reticent” prime ministers in the past, but they have generally been paired with a “more dynamic chancellor”.

Instead, May has Philip Hammond who “compounds” her caution. The result is a government of “ennui and drift”. Having “promised to stand for more than Brexit”, May has “managed to stand for less (given her constructive ambiguity even on that question)”. Rudd’s resignation would be a “non-event” for a “busier” prime minister, as would losses in the local elections. But May, with her lack of direction, is “the plaything of events”.

Immigration policy needs reform

What about Britain’s immigration policy? “Clamping down on immigration” is the issue with which May is most strongly associated, and she will be “reluctant

to admit she was wrong”, says Rachel Sylvester in The Times. But Rudd’s replacement, Sajid Javid, who has become Britain’s first Asian home secretary, has never made “any secret of the fact that he has a much more liberal approach to immigration than the prime minister”.

He has repeatedly called for students to be excluded from the immigration figures and friends say he disagrees with the Tory goal of reducing net migration to tens of thousands. Javid says he will not use the term “hostile environment”, and an MP who knows him well says he will “emphasise fairness rather than firmness”.

Immigration policy must be firm, says The Daily Telegraph. “Unless crucial departments like the Home Office do their jobs properly, what chance is there of operating credible frontier controls and workable citizenship policies after we leave the European Union?”

Blurring the distinction between Windrush-generation citizens and illegal immigrants is not useful for “producing a workable immigration policy that respects the rule of law and the rights of people who have paid into the welfare system”, adds The Economist. The government has “rightly been condemned for its appalling treatment of the Windrush generation and its obfuscations about whether Britain has targets for the removal of illegal immigrants”.

But the less that “respectable” politicians are willing to talk about controlling immigration, the “more the subject fuels subterranean forces that, like Brexit, suddenly come from nowhere to overwhelm the political system”. It needs to be addressed.