As far as the US equity market has been concerned for much of this year, “everything is absolutely fine and new highs are a God-given right”, Chris Bailey of Raymond James told the Financial Times. But early this week the cosy consensus began to falter. President Donald Trump threatened China with tariffs on another $200bn of goods following their threat to retaliate against the levies on $50bn of imports that America announced last week.

Those comprised import duties on 818 products worth $34bn that will take effect in early July. Tariffs on another 284 products worth $16bn are due later. This week’s renewed sabre-rattling wiped 4% off the Shanghai Composite index, leaving it at a 20-month low. US-led global equity markets slipped too, notably Asia’s. Thanks to global supply chains, slapping tariffs on a good being shipped out of a Chinese port typically “involves the exports of several countries and components made by several companies”, notes Hannah Anderson of JPMorgan Asset Management.

So far, so good

Until this week, investors reckoned that Trump was blustering when it came to trade. Trump first called Kim Jong-un “Little Rocket Man”, but then met him and declared the threat from North Korea over. Similarly, investors appear to assume that the tariffs were “negotiating tactics” that could soon be ditched, rather than “the start of an actual trade war”, says Randall Forsyth in Barron’s. Note, for instance, that for all the fuss about China stealing intellectual property, many of the products in last week’s tariff list were distinctly “old-economy”, including steel pipes. Several weren’t imported at all in 2016. Cathode-ray tube monitors, which were eclipsed by flatscreen displays years ago, are on the list. The apparent upshot? “Sound and fury, signifying little.”

The latest trade rows have also taken place following decades of trade liberalisation, as Arthur Kroeber points out in a Gavekal Research note. Another $100bn of tariffs would raise the overall effective tariff (customs duties as a share of total imports) to 3.4%, “the same as in the pretty liberal 1990s”. However, the trend towards global trade liberalisation has peaked. And because there are no ill effects visible yet, partly because the US economy has been juiced by tax cuts, Trump may conclude there is no harm in continuing.

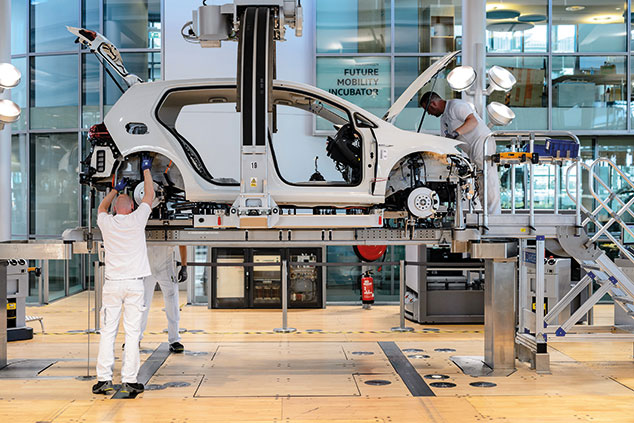

Watch out for cars and Nafta

If he now imposes tariffs on cars and car parts, it would affect around $208bn of car imports and $60bn-100bn of parts, says Kroeber. America’s effective tariff would rise to 6.7%, the highest since 1969. Another danger is a North American Free Trade (Nafta) breakdown. With a populist set to win Mexico’s presidential election in July, and Trump wanting to rally his troops for the mid-terms, “Nafta withdrawal is a non-trivial possibility”. A US exit from the 1994 trade deal could herald a big jump in trading costs, further undermining global growth. Trump’s trade campaigns may be reaching a tipping point.