What is the WTO and why was it set up?

The WTO is based in Geneva and was set up in 1995 to replace the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The latter emerged after World War II, along with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, to foster international economic co-operation. Today, the WTO oversees trade among its 164 members, which include the US, the EU, China and Russia. It provides a forum for countries to design trade rules and settle trade-related disputes. “The WTO was the crown jewel in the effort to build international governance,” says Edward Alden of the Council on Foreign Relations – “a visionary and courageous effort to create predictability and consistency in the trade relations among nations”.

So why is it under threat?

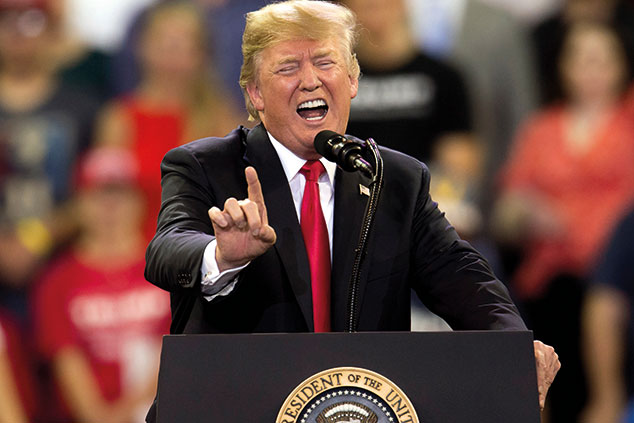

The immediate problem is that the organisation has fallen foul of President Donald Trump’s mercantilist and unilateralist world view. The WTO “has actually been a disaster for us”, he says, even though the US has hardly done badly out of it. Washington has won 85% of the 117 WTO cases it has brought against foreign trading partners. There are now two major headaches for the WTO thanks to Trump’s America First policy.

What are they?

Firstly, Trump has been blocking the appointment of new judges for the WTO’s appellate body. If he continues to withhold support for new appointments, by the middle of next year the panel will not be able to adjudicate any disputes, as Simon Nixon points out in The Wall Street Journal. Because 80% of WTO panel rulings go to appeal, this would “[paralyse] the entire WTO system for enforcing trade rules”.

Secondly, Trump invoked a very rarely used rule to justify his steel and aluminium tariffs. He claimed that America’s national security was at stake thanks to its dependence on imported steel and aluminium. (Trade experts have noted that the US produces more than two-thirds of the steel it uses.) Now, the WTO is in an impossible position. It has to decide whether to back the EU and China, who say this is a case of illegal protectionism – thus disputing America’s national interest – or back Trump and legitimise a huge loophole in global trade.

Is the WTO’s crisis due solely to Trump?

The system has actually been struggling for some time. Since 1945, global trade has been gradually liberalised in successive rounds of multilateral talks. But this process stalled at the turn of the century: the so-called Doha round of talks, launched in 2001, never produced any significant measures, and gradually petered out a few years ago.

The WTO has also proved unable to resolve recurrent complaints about China. For instance, the US says the Chinese state has rigged the system against US firms: they oblige American companies to hand over their technology without keeping their intellectual property rights when they form partnerships with Chinese companies. The EU and Japan have voiced similar complaints.

What happens next?

By invoking the national-security pretext, the US has thrown “the rulebook out of the window”, says Alden. Washington seems to be aiming for a “free-for-all negotiating process in which its trading partners are now expected to come [begging] to the White House… a clear violation of the understanding that trade will be conducted under internationally agreed rules”. Trading arrangements that have successfully insulated the global economy from chaotic trade wars for 70 years could now unravel.

So it’s back to the 1930s?

Not necessarily. We may revert to the GATT system, a looser set-up that had plenty of rules but no legally binding system of settling disputes. Countries would often ignore the rules if they

didn’t suit them, and used to improvise if their interests clashed. Following US complaints about unfair trade in the 1980s, for instance, Japan voluntarily curtailed exports of steel and cars to America. The US used its position as Japan’s biggest overseas market, and its protection of Japan against the Soviet Union, as leverage.

However, now that the US appears bent on unilateralism, other countries may be tempted to respond. The WTO’s director general, Roberto Azevêdo, told The New York Times recently that if members “simply begin to take matters into their own hands… we may be in a situation where the global economic environment could deteriorate very fast”. He added: “These measures tend to exacerbate nationalistic sentiments.”

Is there a more upbeat scenario?

Not everyone is that gloomy about the impact of the US effectively removing itself from the world’s multilateral trading system. One senior WTO official told the FT: “If the US leaves that will be a colossal blow. But let us also keep in mind that the US [as a destination] right now accounts for just 14% of global exports. Yes, it will be a terrible loss. But I don’t think it will be the end.”

Bear in mind, too, that not all tit-for-tat trade spats escalate into global trade wars in the way that America’s Smoot-Hawley tariffs did. In 2009, when Obama imposed tariffs on Chinese tyres, China slapped tariffs on American chicken feet, which are a popular snack in China. As a result, US poultry producers lost $1bn. A few years later the US and China dropped their tariffs. According to Capital Economics, Europe and Japan may refrain from aggressive retaliation in an effort to preserve what remains of the global free-trade system for a post-Trump world.