This article is taken from our FREE daily investment email Money Morning.

Every day, MoneyWeek’s executive editor John Stepek and guest contributors explain how current economic and political developments are affecting the markets and your wealth, and give you pointers on how you can profit.

In this week’s issue of MoneyWeek magazine

●

Don’t get oil-shocked – prepare your portfolio for pricier crude

●

Brave investors should venture out to frontier markets

●

The investment trust that refuses to believe in the end of the world

●

Three Aim-listed firms that will thrive in a post-Brexit world

●

Efficient markets theory and tennis

● Share tips of the week

Not a subscriber? Sign up here

It’s one of the most controversial topics in finance right now.

It’s also quite technical. So it can sound a little bit boring.

But given that it has proved to be an almost infallible recession indicator (at least, according to some experts), it’s probably something we should be keeping an eye on.

We’re talking about the inverted yield curve.

What is a yield curve anyway?

You might be asking right now: “What’s a yield curve, never mind an inverted one?”

Well, you’ve come to the right place. Here’s a quick and painless explainer.

Let’s say you’re fixing your mortgage rate. Would you expect to get a lower interest rate over two years or ten years?

The obvious answer is that you’d expect to get a lower interest rate over two years. After all, you’re borrowing for a much shorter period of time and there’s a lot more certainty over what’s going to happen in the near future for the lender, than a decade hence. And that’s what happens, if you look at mortgage rates.

It’s a similar thing for government bonds (and other types of lending). A two-year bond will yield less than a five-year bond, which yields less than a ten-year. And if you plot those figures on a graph, then you get a nice upwards-sloping curve – the yield curve – as a result.

At least, that’s what normally happens.

However, sometimes the gap (“spread”) between the two-year bond and the ten-year gets narrower. In other words, the ten-year doesn’t pay much more than the two-year. When this happens, the yield curve is said to be flattening (because it is).

This typically happens because investors are increasingly worried about the future prospects for the economy. If they are willing to accept basically the same interest rates in the future, it means they don’t expect interest rates to be high in the future, because they don’t expect growth to be particularly strong.

And if they get really gloomy, the yield curve inverts. In other words, rather than sloping up, or being flat, it slopes down, so that you can actually get a better yield on a two-year Treasury than on a ten-year. At this point, investors might be betting that future interest rates will be lower than present ones because they expect central banks to have to cut rates to combat falling growth.

This matters because right now, the yield curve is flattening. Indeed, the spread between the two and the ten-year yield hit its lowest since 2007 last week. It’s not inverted yet. But it’s close.

And the trouble is, an inverted yield curve has a great record of predicting recessions. In fact, every US downturn of the last 50 years has been preceded by an inverted yield curve.

Dismissing the flattening yield curve is a bit foolhardy

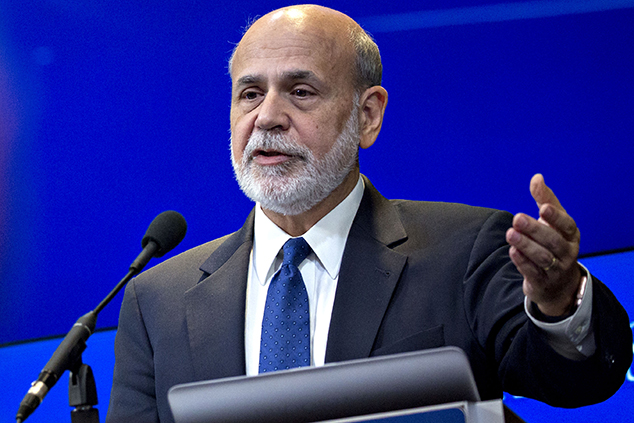

A number of explanations have been given for why the flattening yield curve is nothing to worry about. Last week, for example, former Federal Reserve chief Ben Bernanke said that “it would be a mistake to think that the unexpected flattening of the US yield curve signals a looming recession”, reported the FT.

Bernanke’s argument is that quantitative easing (QE) overseas means that foreign money is flooding into long-dated US Treasuries in a hunt for an income, thus keeping yields down.

Let’s leave to one side the hilarity of watching Bernanke, the primary architect of QE, decrying its distortionary impact on the market.

Instead, let’s consider the fact that in 2006, the yield curve inverted pretty much the same day that Bernanke took charge of the Fed. Back then he blamed it on a foreign savings glut, and told everyone not to worry too.

And he was wrong then, in a quite spectacular manner.

Are there any other reasons not to worry? There’s an argument that demand for safe-haven assets (in the form of long-term developed-world government bonds) has permanently picked up, which is probably true. But it’s similar to the “savings glut” argument again.

In reality, the simplest conclusion is also the least pleasant one: the yield curve is probably flattening because people are right to be worried about the economy. We have mounting trade wars, which aren’t good for growth. We have incredibly low unemployment – which is good right now, but it’s also something you see towards the end of the economic cycle rather than the beginning.

Now, it’s worth remembering that we’re not there yet. The yield curve has yet to invert. And with Donald Trump putting pressure on the Fed to hang back, maybe we’ll see the Fed use the yield curve as an excuse to slow down on its planned pace of rate rises.

Indeed, the yield curve sharpened steeply (from a very shallow position, admittedly) on Friday as the yield on the ten-year started to perk up.

But I’d strongly suggest keeping an eye on this, because if the yield curve does invert, it’s an unusually reliable sign that a downturn is coming in the near future, and we’d certainly need to take account of it for our investment scenario planning.