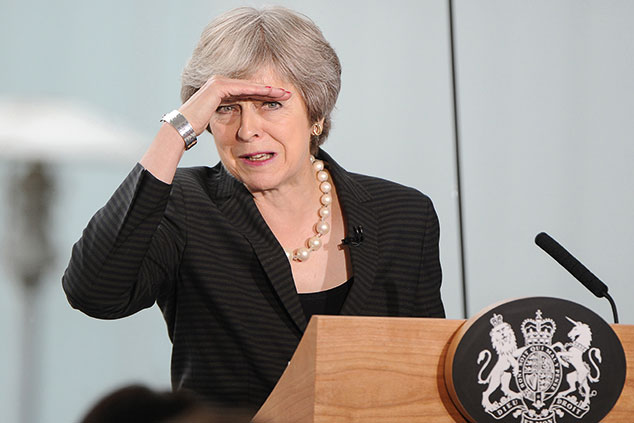

As MPs return to parliament, Theresa May is facing “the most turbulent three months in parliament in living memory” as she “struggles to do a deal with Brussels” and “see off her Brexiteer MPs”, says The Times. On the one hand she faces “an all-out assault” on her Chequers proposals from Brexiteers, including Boris Johnson who has publicly attacked them. On the other, the EU’s Michael Barnier is “still demanding that Britain adopt one of the off-the-shelf relationships with the EU that already exists”. Sources say that he has already told Brexit minister Dominic Raab “that the Chequers plan is not going to fly”.

The enemy in her own ranks

If she wants to get the Chequers plan through parliament, the prime minister faces an uphill climb, says George Parker in the Financial Times. Because “most Labour MPs will oppose any deal”, the PM needs “the backing of almost all Tories to win the vote”. Unfortunately, “the eurosceptic uprising against her Chequers plan” is echoed by some pro-European Tory MPs, who believe it is a “worst of all worlds” compromise that would leave Britain “as an enfeebled EU rule-taker”. Perhaps her only hope is to convince the Conservative right that opposing her plan might lead to “no Brexit at all and a descent into internecine Conservative warfare”.

Good luck with that, says The Daily Telegraph. May’s attempts to sell the plans to both Conservative party members and MPs over the summer have proved to be a “waste of time”, with many viewing Chequers “as a betrayal of Brexit”. If they dislike the current proposals then they will hate a revised version that contains the concessions needed to sell the deal to Brussels. The prime minister’s best course of action would be to make a virtue of necessity and “return to the theme of a no deal”. This would have the benefit of forcing “the Europeans to start offering solutions to problems that they have thrown up”.

The 11th hour

Britain leaving the EU without at least a withdrawal agreement would be a disaster and would “wreak havoc on trade”, says Anand Menon in The Guardian. However, the good news is that such an outcome is “still unlikely”. While “there are still significant hurdles to be cleared in the negotiations”, the fact remains that “both sides have a vested interest in securing a deal – or at least postponing the day of reckoning”. And past experience shows that “the 11th hour is when the EU tends to strike its agreements”.

But with the government stymied, kicking the can down the road through an indefinite transition period might not be such a bad idea after all, says Bloomberg. Obstacles to executing the two-year transitional agreement “can and should be set aside immediately, so that the looming cliff-edge exit can be ruled out”. At the same time, “the planned transition should then be extended for as long as necessary to come to terms on a future trade and security partnership”. While neither side might like this, the reality is that “imposing phoney deadlines on a complex process only adds to the prevailing uncertainty”.