Africa is a very risky frontier market. But it is also home to a motley mixture of great growth businesses and value stocks. African research specialist Christopher Hartland-Peel has spent decades tracking the 30 biggest companies on the various stockmarkets of sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa).

As you’d imagine, it’s a jumble of banks, brewers, telecoms businesses and cement companies (think of all those new roads and buildings). The local markets these businesses are listed on vary enormously. The biggest is Nigeria, with a total market cap of $36bn, followed by Kenya, with $24bn. The Ivory Coast comes third ($8.4bn), just ahead of Zimbabwe, which despite all the turmoil still has a stockmarket worth $7bn.

Africa’s bargain large caps

According to Hartland-Peel many of these big businesses trade at relatively low valuations. Seven out of the top 30 companies by market cap pay out a dividend yield of more than 5%, and ten trade at a price-to-book ratio of less than 1.5. Ten of these 30 trade with a price-earnings ratio of less than ten, but seven boast a return on capital employed (a key gauge of profitability)of more than 25% per annum. The risks are also obvious: currency volatility is a given, as is vulnerability to commodity prices, trade wars and political tension. One of the best ways to get in is via a fund that invests across the continent – my own favourite is the Africa Opportunity Fund (LSE: AOF).

The fund has had a tough time with some of the stocks in its portfolio – a reminder that even with specialist local knowledge, investing in this continent can be a nightmare. In Zimbabwe, for instance, its property investments have suffered rising vacancies and growing arrears, but the manager still expects the country to attract fresh capital and investments if the political environment allows (the country accounts for around 10% of assets).

I think the AOF is right in its assessment of potential change in Zimbabwe. This former colony falls firmly into what I think adventurous investors might call a recovery story. Many of the biggest successes in frontier markets stem from long-term, patient investing in difficult, illiquid markets. Smart investors frequently head into a slowly reforming country long before the herd. They then wait for a steady increase in confidence as the local economy opens up to the outside world. Mongolia was a classic example.

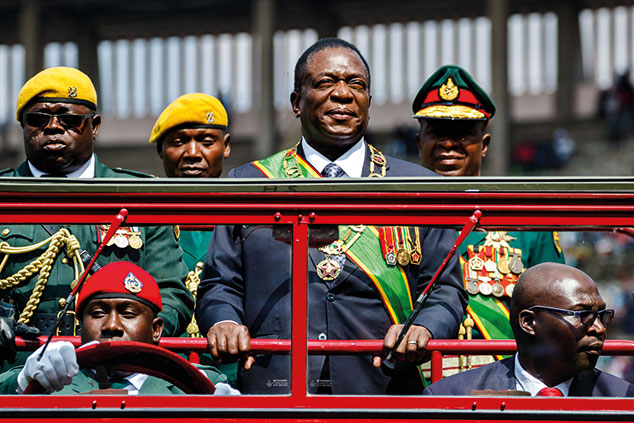

The good news is that there is a new president in this once mighty economic powerhouse, Emmerson Mnangagwa. The bad news is that he’s still from the same old elite – the Zanu PF party. Still, the new leaders seem to have realised that financial stability and a clearer asset-ownership framework are required to boost foreign direct investment. Existing joint ventures should thrive as long as the foreign investors can continue to get along with their local, indigenous co-owners.

Caledonia: a triple-play

That brings me nicely to Caledonia Mining (Aim: CMCL), an interesting triple-play. This local gold miner’s shares are cheap and offer a decent 4.2% yield. There’s plenty of cash on the balance sheet and it’s profitable – the cost of production is around $832 an ounce but the gold fetches approximately $1,200.

As a gold miner, Caledonia should be a useful hedge against future stockmarket volatility. It’s also a way to bet on Zimbabwe. If the country does recover, there’s a chance the government might allow foreign investors to increase their equity stake in local businesses, which would bode well for UK-based investors in Caledonia. The mine’s safety record is ropey and it needs investment. But the shares have come off sharply recently and I think much of the bad news is now in the price.