Financial markets are so busy looking to the future that the past gets forgotten quickly. So having work publicly dismissed as “absolutely silly” is unlikely to cause lasting damage to a firm’s reputation. But when the words come from Warren Buffett, one of the world’s most respected investors, they tend to stick. No wonder, then, that “proxy advisers”, the groups he was attacking when he made his remarks 15 years ago, have come under ever-closer scrutiny recently.

Proxy advisers are firms that get paid by investment and pension funds to recommend how to vote when listed companies hold a ballot. They will also vote on fund managers’ behalf under terms agreed with them beforehand. Following mounting criticism of their behaviour, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the US investment watchdog, and lawmakers have raised the prospect of greater regulatory oversight.

Power without responsibility

This is no sideshow. The two largest advisers – Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis – are said to control 97% of the US proxy voting market, eclipsing others such as Egan-Jones. They’re also the largest global operators and prominent in the UK market, which has its home-grown advisers PIRC and IVIS, as well. These groups are often in the spotlight giving voting recommendations on various companies, including giants such as WPP, AstraZeneca and Shell.

The sector has gradually expanded over the past 30 years or so with minimal oversight. As funds proliferated and came to hold more and more of the shares in circulation, it became logistically difficult for managers to research and vote on every issue up for debate at all the companies they owned. So the proxy advisers sprang up to do it for them. Research shows they do shift votes, giving them significant sway over the boards of blue-chips as well as minnows – a power that demands supervision. How votes are cast, whether electing directors or approving takeovers, can materially affect shareholders’ interests and returns, and getting it right is crucial.

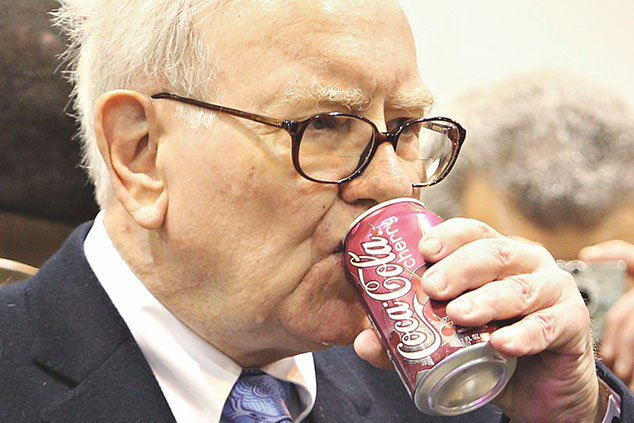

Get it wrong, on the other hand, and you irk the likes of Buffett while undermining credibility. His gripe with proxy advice goes back to 2004, when ISS recommended throwing him off the board of The Coca-Cola Company. It reasoned, implausibly, that because other companies he invested in did business with Coke, he wasn’t independent.