This article is taken from our FREE daily investment email Money Morning.

Every day, MoneyWeek’s executive editor John Stepek and guest contributors explain how current economic and political developments are affecting the markets and your wealth, and give you pointers on how you can profit.

China has just posted its slowest economic growth since 1990.

We all know that Chinese economic statistics are even less reliable than most. The fact that this level of slowdown is being acknowledged suggests that China is aware that it’s very obvious that the economy is not as strong as it once was.

In turn, that means markets are upbeat about the idea that the country will “stimulate” its economy with looser monetary and fiscal policy.

But that does raise the question: what if that doesn’t work?

China’s spat with the US is only just beginning

China’s fourth-quarter GDP figures suggest that growth came in at an annual rate of 6.4%. That’s the slowest growth in nearly 30 years. Overall, in 2018, growth came in at 6.6%.

We all know that these figures are fictional (or “smoothed”, at the very least). Pantheon Macro reckons that in fact, GDP growth has slowed to 5.8%. Capital Economics reckons it’s even lower, at 5.3%.

And to put some colour on that, research consultancy Enodo Economics points out that China’s slowdown has hit sales at smartphone giants Apple and Samsung. Iron ore imports fell in 2018 for the first time since 2010. Domestic car sales are down for the first time in nearly 30 years.

The Chinese government certainly knows that there’s an issue here. Tax cuts have been pushed through, while monetary policy has been loosened. The hope is that this will continue. As a result, both Pantheon and Capital reckon that growth will start to pick up later in the year, due to “expanded policy stimulus,” as Julian Evans-Pritchard of Capital Economics puts it.

But there are deeper problems here. One is the conflict between the US and China. The other is that the overall approach and tone of the government towards economic development and freedom has changed.

On the first point, as far as the market is concerned right now, the US and China will reach a good deal on trade. The mood music has been optimistic so far.

Now, we all know that markets believe what they want to believe – right now, they’re in rebound mode, so they are inclined to expect the best for the trade talks. We also know that Donald Trump can change his mind very rapidly. When he feels under pressure he likes to create a distraction.

However, it does seem likely that Trump would like to get a deal done to announce a victory, and clearly the Chinese do too. The problem is, as Diana Choyleva of Enodo Economics points out, that this particular spat is just the tip of the iceberg.

As far as Choyleva is concerned, Trump is merely a manifestation of the fact that the West, and the US in particular, has been getting fed up with China’s particular development model for some time now.

The decision to turn itself into a manufacturing powerhouse by undercutting wages in global labour markets and acquiring valuable intellectual property from foreign rivals as the price of doing business worked in its favour for a long time. The financial crisis spelled the beginning of the end for that model, but the frustration had already been building.

So the current trade wars are just a start, says Choyleva. The tension between the US and China is now openly out there. They are rivals in the technology sphere; they are military rivals, obviously; and they are rivals for financial influence – the renminbi is nowhere near as important to the world as the US dollar is right now, but unlike the euro, it is far more of a threat.

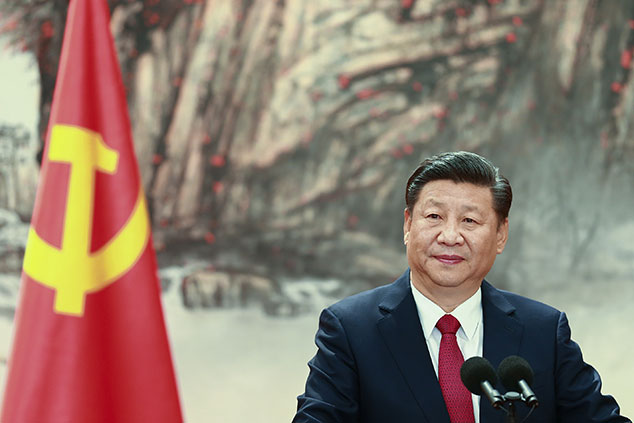

China isn’t liberalising anymore

Perhaps even riskier is the fact that Xi Jinping, unlike the reformer Deng Xiaoping, is not really on board with this “opening up the economy” idea. He’s pretty old school when it comes to business and the middle classes – he sees them as potential troublemakers who need to toe the line. The government – or rather the Communist Party – is the boss, and they had better not forget it.

As Rana Foroohar points out in the Financial Times, despite his 2017 speech defending globalisation at Davos (lavishly praised by those who allowed their dislike for Trump to blind them to the blatantly obvious), under Xi, China has been “backtracking on reform, encouraging unproductive state-owned enterprises to grow even bigger, reducing competition and exacerbating the economic slowdown already under way.”

He’s also exerting more pressure on the tech sector, “requiring both foreign and domestic companies to engage in more censorship and co-operate with state security efforts.”

This is not an environment to encourage free spending (conspicuous consumption has been a dangerous business for a while in China), nor to encourage entrepreneurialism (you don’t want to take risks or have good ideas when it’s seen as a challenge to the state rather than a valid contribution to society).

What does this mean? It means that whatever short-term relief markets get from any temporary deal between the US and China, there’s no guarantee that it’ll last for long. Choyleva warns that, “unsettled as they are, global financial markets have yet to grasp that this time it really is different in China”.

This tension will be a major source of potential upheaval for markets this year. I’ll be discussing this (and plenty of other topics) in more detail with MoneyWeek regular Tim Price and Netwealth’s Iain Barnes on the evening of 12 February at an event we’re holding in central London – book your ticket now if you haven’t already.