Editor’s note: this afternoon we have a guest post from Tim Price, acclaimed value fund manager and regular MoneyWeek contributor. Come and see Tim talking to MoneyWeek executive editor John Stepek and Iain Barnes of Netwealth on February 12th – get your tickets here now.

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience, and more patience. The majority of investors do not possess this characteristic.”

– Canadian value investor, Peter Cundill (1938 – 2011)

This afternoon, I’d like you to help me with a brief thought experiment.

Let’s take a trip back in time.

Sometimes it’s hard to hold on

It is 1971. You are an investor in the US stockmarket. You hear great things about the management of a particular company, so you invest $10,000 in its shares. You also keep an eye on the broader market.

Here is how you fare.

| Year | Value of $10,000 in Company X |

Value of $10,000 in S&P 500 index |

| 1971 | $10,000 | $10, 000 |

| 1974 | $5,708 | $7,456 |

| 1975 | $5,422 | $10,229 |

After four years, the value of your investment in this supposedly great company has nearly halved. The broad market has also sold off during the same period, but has now bounced back to above break-even.

What do you elect to do? You may well decide to sell.

Let’s fill in the subsequent year’s returns and then take a longer view still:

| Year | Value of $10,000 in Company X |

Value of $10,000 in S&P 500 index |

| 1976 | $13,392 | $12,643 |

| 2008 (Nov) | $14,387,737 | $259,068 |

If you elected to sell, congratulations. You just sold Berkshire Hathaway.

The author Ryan Holiday (writer of The Daily Stoic and Ego is the Enemy, among other books) gave a talk at Google (‘Ego is the enemy’) in which he tells the story of the American football coach Bill Walsh, who in 1979 was hired as head coach to the San Francisco 49ers.

At that point the 49ers were not just one of the worst teams in football. They may have been one of the worst teams in all of professional sport.

Walsh immediately set about bringing change to the team, trying to turn around the fortunes of a side that had become mired in a culture of losing. The year before Walsh took over, the poor 49ers went 2-14 – they won just two of their 16 games. Walsh set to work and hired good players. His first season as a coach saw the team go 2-14 again. Not only that, but the team still holds the record for being the only team to lead in 12 games – and lose all of them.

The following season was almost as bad. The 49ers went 6-10 in 1980 – they won six of that season’s 16 games. The team remained so bad that Walsh almost quit halfway through the season.

The next season, they won the Super Bowl.

Walsh attributes the success of the team to what he terms the “standard of performance” – the standard that he imposed on players, which was pretty stringent. There would be no sitting on the playing field; coaches had to wear jackets and ties; sportsmanship was stressed “almost to an absurd degree”; the team’s work ethic was prized above everything. Practice routines were scheduled down to the minute.

Walsh’s mantra was that if the team adhered to these standards of performance, the score would ultimately take care of itself. When asked by reporters what his timetable for turning around the team was, he would always reply that he didn’t have a timetable. One of the assistant coaches complained to the owner that Walsh didn’t have a timetable to turn the team around and it wasn’t going to be fast enough. Walsh fired him.

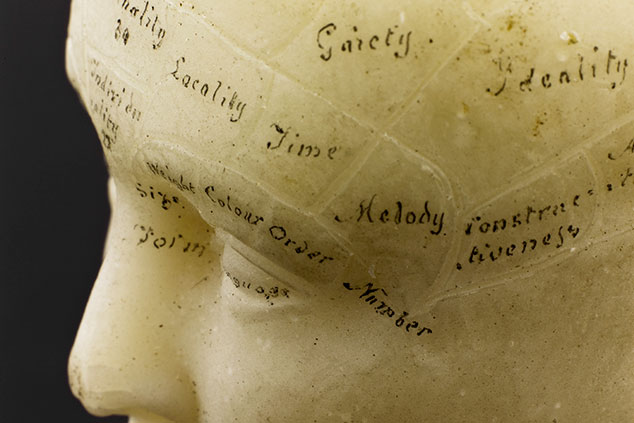

Successful investing does not come naturally to people. Human beings are not evolutionarily well adapted to stockmarkets (for example). Homo sapiens and the human brain started their evolutionary journey on the plains of Africa 300,000 years ago. Stockmarkets have only been with us for a couple of hundred years.

Author and historian Yuval Noah Harari suggests in his book Sapiens that what distinguishes between homo sapiens and our other ancient contemporaries whose evolutionary lines have died out is our enthusiasm for, and adeptness at, storytelling. Whether a story is even true may be less important than just how compelling it is.

Human beings also crave certainty, so we would rather buy into a false narrative than accept that the world is a deeply uncertain and unpredictable place. Which partly accounts for why financial journalism is such an intellectual backwater.

So we seek out interesting-seeming stories and we can barely wait for the conclusion. It is hardly a surprise that so many investors do less well than they might. Addiction to novelty and an unwillingness or inability to be patient make for uncomfortable behavioural attributes.

Investing – and life – is better if you cut out the needless distractions

In 1984, professional investor Robert Kirby told the story of a client and her husband: “Her husband, a lawyer, handled her financial affairs and was our primary contact. I had worked with the client for about ten years, when her husband suddenly died. She inherited his estate and called us to say that she would be adding his securities to the portfolio under our management.

“When we received the list of assets, I was amused to find that he had secretly been piggy-backing our recommendations for his wife’s portfolio. Then, when I looked at the total value of the estate, I was also shocked. The husband had applied a small twist of his own to our advice: He paid no attention whatsoever to the sale recommendations. He simply put about $5,000 in every purchase recommendation. Then he would toss the certificate in his safe-deposit box and forget it.

“Needless to say, he had an odd-looking portfolio. He owned a number of small holdings with values of less than $2,000. He had several large holdings with values in excess of $100,000. There was one jumbo holding worth over $800,000 that exceeded the total value of his wife’s portfolio and came from a small commitment in a company called Haloid; this later turned out to be a zillion shares of Xerox.”

Impatience. Penchant for narrative. The third ingredient that makes for a toxic investment cocktail is distraction-by-way-of-apparent-news.

Rolf Dobelli, the Swiss author of The Art of Thinking Clearly, provides the antidote, and we try to adopt his advice, which among other things is to limit our exposure to conventional news sources and replacing them where practicable with more considered, longer form commentaries (also known as books), podcasts and third-party videos streamed online.

We limit our asset allocation universe to three and only three types of investment: objectively inexpensive listed businesses run by principled, shareholder-friendly management with a sustained record of masterful capital allocation; uncorrelated fund vehicles that track price momentum across multiple markets; and real assets that offer the potential for portfolio and inflation protection in the midst of a monumental global debt predicament. We then try and tune out everything else, not least those things that we can not remotely affect.

Perhaps half of what really matters to any investor is not what happens within the market as such, but rather how we respond to it, assuming that we decide to respond at all.

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. John Stepek will be discussing the current state of markets with Tim and Netwealth’s Iain Barnes on the evening of 12 February – tickets here now.