Welcome back.

Merryn is away this week, so I’ve been flying solo on the podcast. We asked you to send in some questions you’d like us to address, so I thought I’d take a crack at answering some of your queries. In this one, I talk about the latest economic fad, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT for short).

Let us know what you think, and if you have any questions that you’d like Merryn and I to address, please do send them in to editor@moneyweek.com. Put “Questions for the podcast” in the subject line and we’ll see what we can do. We’ve already had some excellent questions on inflation and interest rates, which we’ll queue up to address in future discussions.

If you missed any of this week’s Money Mornings, here are the links you need.

Monday: Inflation, Brexit and slowing economic growth: it’s a busy week for Britain

Tuesday: How self-driving cars could be the next genuinely useful investment bubble

Wednesday: A trade war in the US is just the most obvious of China’s problems

Thursday: How to catch the best of a bull market while dodging the big bears

Friday: Why investors should never mistake the economy for the stockmarket

And subscribe to MoneyWeek magazine – it’s even better than Money Morning.

And now, over to the charts.

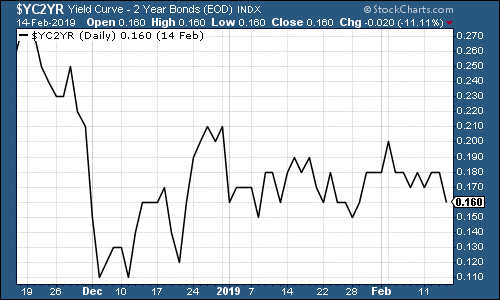

The yield curve (here’s a reminder of what it is) is still dangerously close to recessionary levels, despite the Federal Reserve’s apparent decision to stop raising interest rates.

The chart below shows the difference (the “spread”) between what it costs the US government to borrow money over ten years rather than two. Once this number turns negative, the yield curve has inverted which almost always signals a recession (although perhaps not for up to two years).

(The gap between the yield on the ten-year US Treasury and that on the two-year, going back three months)

Gold (measured in dollar terms) remains in consolidation mode. Investors can’t make up their minds as to whether it’s time to buy stocks again, or if we’re facing a slide in the economy, which might result in inflation falling (not ideal for gold in the short term).

(Gold: three months)

The US dollar index – a measure of the strength of the dollar against a basket of the currencies of its major trading partners – continued to climb gently this week, which isn’t ideal for risk appetite.

(DXY: three months)

The ten-year yields on the world’s major developed market bonds were little changed, as readings from the US, Japan and Germany show.

(Ten-year US Treasury yield: three months)

(Ten-year Japanese government bond yield: three months)

(Ten-year bund yield: three months)

Copper took a breather as the mood fluctuated over prospects for a deal between the US and China. But copper is also a core ingredient in the electric car revolution (as How self-driving cars could be the next genuinely useful investment bubble) and in the longer run, this might matter more than the ups and downs of the trade debate.

(Copper: three months)

The Aussie dollar – our favourite indicator of the state of the Chinese economy – has managed to remain above the $0.71 mark as investors alternately hope and pray that China and the US can do a deal.

(Aussie dollar vs US dollar exchange rate: three months)

Cryptocurrency bitcoin spiked higher last Friday, but spent this week gradually drifting lower.

(Bitcoin: ten days)

The four-week moving average of weekly US jobless claims rose to a one-year high this week, to 231,750, as weekly claims rose to 239,000.

David Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff has pointed out in the past that US stocks typically don’t peak until after the moving average of jobless claims has hit a low for the cycle. Judged by the (very) small sample of past recessions, on average, the stockmarket peaks about 14 weeks after the trough, with a recession following about a year later.

The most recent trough came on 15 September, at 206,000. If that was the bottom, it implies that the market has already peaked, and that a recession may follow this year or in 2020. I still think we need to wait to see until after the US government shutdown disruption is cleared. But for now that chart does not look too healthy. And the S&P 500 has a fair way to climb from here if it is to breach its most recent high – in early October – of 2,950.

(US jobless claims, four-week moving average: since January 2016)

The oil price (as measured by Brent crude, the international/European benchmark) has started to pick up. Saudi Arabia is cutting its production in what Goldman Sachs deems a “shock and awe” move. But more importantly, oil is a “risk-on” asset. If central banks are giving up on the prospect of tighter monetary policy, then that’s likely to be helpful for the oil price.

(Brent crude oil: three months)

Internet giant Amazon has seen plenty of drama in the last couple of weeks although none of it did anything to the share price. First Jeff Bezos took on the National Enquirer tabloid, and then this week he pulled out of plans to build Amazon’s new headquarters in New York. The reaction was predictably mixed. Both sides probably have a point.

It strikes me as self-defeating to let a big company take its jobs elsewhere. But it also strikes me as naive of Amazon not to anticipate a backlash when it goes city-shopping like this – you can just imagine the moans if Amazon had decided to open its HQ in London and been given around £2bn-worth of tax incentives to do so, while local shops and small businesses are being crushed by ever-rising rates.

You have to remember, because it was easy to forget in the early 2000s and late 1990s, when push comes to shove, politics trumps economics and governments have more power than companies.

Maybe the benefits of all those jobs outweigh the strain on the infrastructure, and the cultural upheaval (interesting, isn’t it, that the same arguments made against gentrification are often those that are made against uncontrolled immigration, yet one set of objections is deemed much more valid than the other).

But if people are no longer willing to accept that at face value, then companies are going to need to rethink their approach.

(Amazon: three months)

Electric car group Tesla saw its shares continue to edge lower amid growing concerns about competition, with a lot of rival electric and automated vehicle groups raising funds this year.

(Tesla: three months)

Have a great weekend.

Until next time,

John