This article is taken from our FREE daily investment email Money Morning.

Every day, MoneyWeek’s executive editor John Stepek and guest contributors explain how current economic and political developments are affecting the markets and your wealth, and give you pointers on how you can profit.

Markets had a bit of a scare on Friday.

German manufacturing data was ugly – the sector is now shrinking, hit by an apparent slowdown in demand for cars.

But the scariest piece of data came from the US – and it wasn’t even a piece of economic news.

Instead, we watched in horror as the yield curve… inverted.

What do you mean, you’re not horrified?

Give me five minutes and you will be.

Well, sort of.

What is a yield curve anyway?

The yield curve between the three-month US Treasury bond and the ten-year bond has inverted.

What does that mean, in English?

Firstly, a Treasury bond is US government debt – it’s an IOU from the American government. The yield is the amount of interest it pays, in percentage terms, at the current price. So if you can buy the IOU for $100, and it pays $5 a year interest, the simple yield is 5%.

As the price goes up, the yield falls. As the price goes down, the yield rises. It’s like a see-saw.

There are a few things that usually hold true for bond yields.

The longer you lend money to someone, the more interest you expect them to pay – that’s because the longer your money is sitting with someone else, the more chance there is that inflation will eat up your returns. (There’s also more chance they’ll default, although that risk is usually deemed as negligible to non-existent with US government debt.)

So most of the time, you’d expect a ten-year bond to yield more than a three-month one.

So now plot this on a graph. On the x-axis, you have “length of time until loan is paid back”. On the y-axis, you have “yield”. The yield you demand for lending over three months would be lower than the one for a year, which would be lower than the one for two years, which would be lower than the ten-year one, and so on.

So if you plot the yield over time, you would expect it to curve upwards. And that’s your healthy yield curve.

When the yield curve turns down instead, that’s an inverted yield curve. It just means that investors are accepting lower yields for lending over longer periods than over shorter ones. And it’s bad news.

Why? Because if you think that it’s a good idea to lock in a 2.5% yield over ten years today, but you’re also demanding about the same to lend over three months, then that suggests that you don’t think interest rates are going to rise any time soon.

And the only real reason to think that rates won’t rise is because you think economic growth is going to be sufficiently weak that there will be no inflation, and the central bank might even have to cut rates in the near future.

In other words, an inverted yield curve indicates that markets think we’re heading for interest rate cuts, which almost always is the result of a recession.

How scary is the inverted yield curve?

So how worried do you need to be? Every recession since World War II has been preceded by the yield curve inverting in this way, usually within about a year. So that’s scary.

However, as Tan Kai Xian of Gavekal points out, “not every inversion has been followed by a recession.” So there are false alarms. And Xian reckons this might be one of them.

He points out that the same thing happened in 1998 during the Asian financial crisis. That run – while it did end in tears – still had quite a way to go.

There’s also the fact that, as James Mackintosh points out in The Wall Street Journal, the era of quantitative easing (QE) has made it easier for yield curve inversion to happen.

Put very simply, in more normal times you’d have a bit of excess fat (called the “term premium”) on longer-term yields. QE has trimmed that to the bone – so there’s no cushion there anymore. That means inversion can happen as the result of smaller anticipated cuts to rates than normal.

Moreover, the inversion also needs to be sustained for an average of three months to be valid. In the previous false alarm example – 1998 – the inversion only lasted for a few days.

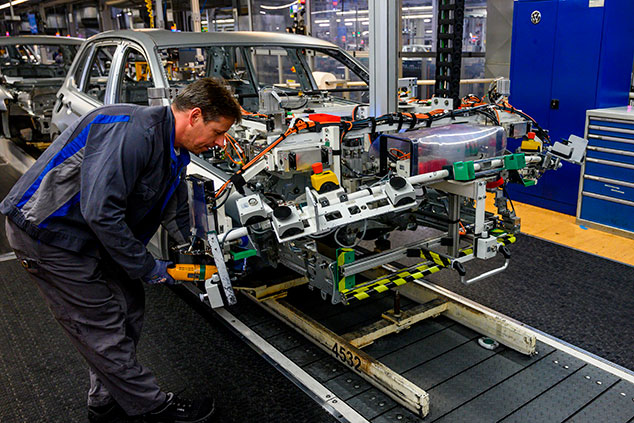

There are other reasons to be wary. The German economy might well run into trouble. However, this has at least as much to do with the rapidly changing car market as slowing demand. The diesel scandal and competition from electric and self-driving specialists have left old-school car makers of the kind Germany is best-known for, struggling to catch up.

In other words, for the car industry – something of a focal point in this particular growth scare – this is as much a disruption story as it is a recession story. Of course, that could still be very tricky for the global economy, but my point is that there are good reasons for car-dependent economies to struggle, ones that go beyond a simple slowdown.

I’m keeping an eye on the two- and the ten-year curve, which hasn’t quite inverted yet. This particular indicator has a better record than the three-month to ten-year curve (it’s so far proved pretty much infallible, although even then, a recession can take several years to turn up). I’ll keep you updated on that every Saturday.

Meanwhile, as always, stick with your plan. It’s good to keep an eye on what’s going on in the economy, particularly when you have relatively reliable indicators to check. But the economy is not the market.

When it comes to markets, your focus should be on buying good value stocks and avoiding expensive ones. Only very rarely do these things coincide with the state of the economy.