On 24 April, news was leaked that the UK government had decided to allow non-core parts of the UK’s 5G network to be built by the Chinese telecoms equipment maker, Huawei. Robert Strayer, US deputy assistant secretary of state for cyber policy, warned allies that if they used “untrusted suppliers” to build new telecom networks, Washington would have to “reassess the ability for us to share information”.

Britain’s decision is significant because it is a member of the “Five Eyes” intelligence-sharing alliance led by the US, completed by Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Huawei is already blocked from developing 5G networks in the US, Australia and New Zealand, and Canada is considering it too. Japan and Taiwan are similarly unconvinced by Huawei’s denials that it is “controlled by the state or that its kit could be used to spy”, says the Financial Times.

Justifiable concerns

Washington’s security concerns are justifiable, says The Economist. China has a history of “electronic espionage” and is a “prodigious hacker”, purloining everything from plans for the F-35 fighter jet to a database of millions of American civil servants. “Last year CrowdStrike, a cyber-security firm, put China ahead of Russia as the most prolific sponsor of cyberattacks against the West.”

Britain, however, has “long-argued that such threats can be managed without banning Huawei outright” and this is sensible. Blocking Huawei does “relatively little” to eliminate the risk of cyberattacks because hackers usually gain access to networks via flaws in software coding. Hence Russia’s ability to “cause mayhem” despite its lack of a commercial role in Western telecoms networks.

A ban would also carry “geopolitical costs. If an open system for global commerce is to be saved, a framework has to be built for countries to engage economically even if they are rivals.” A ban by a few American allies “risks splitting the world into two blocs” (Huawei says it has signed 40 5G contracts, more than half in Europe). Britain has had a system for vetting Huawei’s systems and software since 2010. This should continue. And if Huawei falls short of Britain’s high standards, “it is easy to switch firms”. A “u-turn is always possible”.

Really, asks Charles Parton in the FT? “When its equipment is embedded? At what financial cost? And at what political cost with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)?” There’s also the fact that experts, including the head of the Australian equivalent of GCHQ, say it’s “not safe to distinguish between core and periphery”. On top of that, Huawei’s technical performance is “lamentable”. “Its deficiencies are ripe for hackers to exploit.”

Maybe, but other major suppliers, including Cisco Systems and Nokia, have been found to have backdoors or software vulnerabilities too, says Leonid Bershidsky on Bloomberg. The difference is that they are expected to deal with these issues as best they can, at their own pace. That is no longer the case with Huawei, which is “held to impossible standards”.

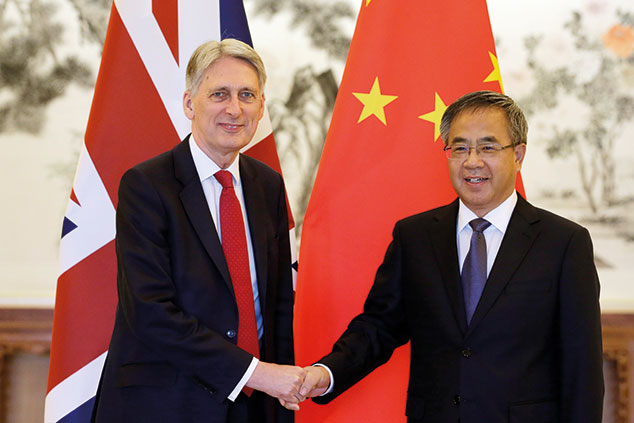

It’s about values, says Edward Lucas in The Times. “On most fronts Britain is quite prepared to grovel.” Philip Hammond has just flown to Beijing to seek a role for British firms in reviving China’s “faltering” Belt and Road initiative. In “any bilateral negotiations, a country of our size will start from a position of weakness. But the danger is not just of a hard-pressed and isolated Britain being bossed around by China’s Communist Party. Our stance also costs us support among our closest friends and neighbours, which want to take a tougher line. In short, we abandon our principles and allies in order to put ourselves at the mercy of a dictatorship.”