This article is taken from our FREE daily investment email Money Morning.

Every day, MoneyWeek’s executive editor John Stepek and guest contributors explain how current economic and political developments are affecting the markets and your wealth, and give you pointers on how you can profit.

We are talking gold in today’s Money Morning – and with good reason.

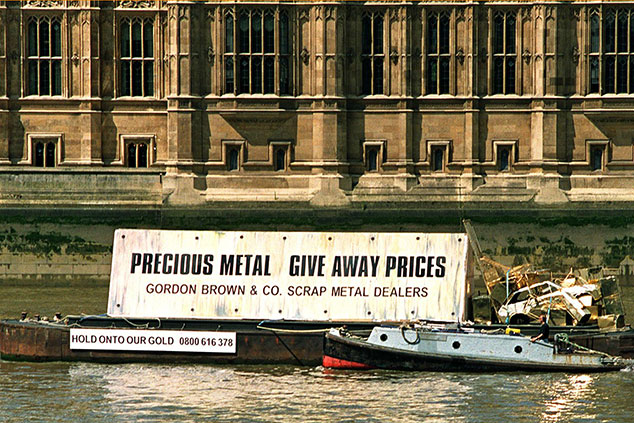

This week marks the 20th anniversary of what must be the worst investment decision of any developed world leadership in modern times.

Gordon Brown’s sale of Britain’s gold at the bottom of the market.

Is this the most impressive feat of market timing ever seen?

In May 1999 the New Labour government, with Gordon Brown as chancellor of the exchequer, began selling Britain’s gold. It was a decision taken against the advice of both the Bank of England and Britain’s bullion dealers.

Over the next three years, Brown sold 56% of the UK’s bullion reserves. To be precise, 401 of the UK’s 720 tonnes.

Instead of selling, and then announcing the sale after it was complete, Brown announced the sale to the international markets beforehand. The effect was to drive the gold price lower – to a price not seen since 1979, 20 years earlier.

The average price achieved was $275 per ounce. Today the gold price is a thousand dollars higher – $1,275 per ounce. The decision has cost $12,892,450,750. So far.

Today that low in the gold price is known as “Brown’s bottom.” I illustrate it here.

Brown has since justified his decision saying that the gains he made in other currencies more than made up for the loss in gold, but given that gold was just about to begin a ten-year bull market against all currencies, I struggle to believe that. It would have taken some extraordinary forex trading to beat gold over the period.

Still to this day, I cannot understand why those decisions were taken. There was no need to sell gold. The government was not under any extraordinary pressure at the time. Not only was there no pressing need, Brown was repeatedly advised, it is claimed, not to sell. So why he then went on and sold is mysterious.

One explanation is that the aim was to provide both moral and financial support for the euro at its birth without having to join. If that’s the case, it is not a good enough reason.

But the absence of need is why many have gone on to suspect that his actions were taken as part of a global conspiracy to suppress the gold price. It’s possible. Then again, it may just have been a very stupid decision. We all make them.

The episode does show one thing, however. There are people who get gold, and people who don’t. Brown clearly didn’t. As gold has lost its role as the backbone of the international money system, its significance as a strategic asset has faded in the minds of many.

Maybe it is an antiquated irrelevance. But, even if it is, gold will always be the money of last resort. And in that regard it is extraordinary that a chancellor would disband a national asset of such potential importance so unnecessarily. One day we might need it.

Believe it or not, I had some personal contacts high up in the Cameron administration, and I was repeatedly urging them to use some of the money created via quantitative easing to buy back what was sold. Needless to say, my pleas fell on deaf ears.

Which brings us to today.

Gold will be stuck in a range for sometime – but hang on to your core position

For six years now, gold has gone nowhere. There has been false dawn after false dawn. But all rallies end at $1,370.

For ten years between 2001 and 2011, gold was the go-to asset. The must-have bedrock of any portfolio. Gold miners gave you the added fizz.

That all changed in September 2011, when gold hit $1,920. For no apparent reason, apart from the fact that it had run a little ahead of itself, gold stopped going up. It started going down instead.

There were plenty of reasons for it to go up – political crises in Europe, zero-interest-rates policies, money-printing, rampant asset-price inflation – all the usual reasons were there. Gold fell instead.

The skids really kicked in in 2013, and the eventual low came two years later in 2015 at $1,060. But viewed in isolation, the last six years in gold has been the story of an asset going nowhere. Across the wider investment landscape there have been bull markets galore: US stocks, tech, 3D printing, bitcoin, cannabis, battery metals – you name it.

But gold? Nada.

The narrative keeps coming back – the time to buy gold is when no one else cares. Nobody cares now. But nobody has cared for six years.

Every year we get a little rally. Everyone gets excited. The price rises $100 or $150 dollars. Then it runs out of steam. The same thing happened this year. I remember writing about it. My colleague John Stepek writes the titles for my articles – not me – and I thought this one was a beauty: “The gold bulls are back – so let’s just be careful out there.”

I have, as regular readers will know, a large part of my net worth in gold. I’m glad I do because it has protected my portfolio against Theresa May and Mark Carney.

But I am thinking in sterling. In US dollar terms, this is no bull market. Gold is stuck in a tired range. It will have its day again, but a stagnant market is a stagnant market and there is not a lot you can do – except keep your powder dry and wait for attitudes to change, which they will.

Even if you roll the trading part of your portfolio in and out of gold, according to circumstances, you should always keep a core position. Selling it down was the mistake Gordon Brown made.

I still don’t think we are ready for another multi-year secular run in gold just yet. It will come, but I rather expect a couple or three more years of what we have now: range trading. If we get through $1,360-$1,370 I might re-assess, but for now that level remains an insuperable wall.

Each year the summer months usually provide the annual low for gold. Looking for lows in the May-August period, with a view to offload in autumn or winter for a 15%-20% gain has proved a viable strategy. So I have my ears, eyes and nose out for oversold summer markets.

Greater minds than my own will disagree, but that’s about as excited as I can get at the moment.

• Dominic Frisby is author of the first (and best, obviously) book on bitcoin from a recognised publisher, Bitcoin: the Future of Money?, available from all good bookshops (and a couple of rubbish ones too). Follow Dominic – @dominicfrisby