Most cells in the human body are particular to one type of organ or function: skin cells, liver cells, or heart-muscle cells, for instance. Stem cells, however, are essentially a blank canvas that can develop into any type of cell. This in turn gives them vast life-saving potential, as a recent project at Imperial College London illustrates. Researchers grew stem cells in a gel and managed to transform them into patches of heart muscle measuring three by two centimetres. These patches could be used to strengthen the heart muscle in patients who have just had a heart attack. This technique would be a major breakthrough, since heart failure affects nearly one million people in Britain alone and the only way of reversing the damage caused by a heart attack is by carrying out a full heart transplant.

We’re not there yet. So far researchers have only implanted stem-cell heart patches in rabbits, but these experiments have been successful. Damaged left ventricles in the rabbits’ hearts recovered within weeks of the operation. The implanted patches adapted seamlessly, with blood vessels growing into them. The next step will be clinical trials on humans.

The 2012 breakthrough

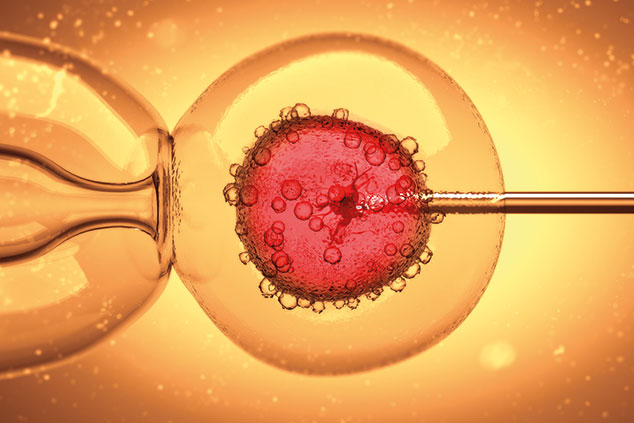

Only a few years ago there was only one source of stem cells: embryos that had been donated or aborted for research. This ethically fraught situation can now be avoided thanks to a technological breakthrough recognised by the award of the 2012 Nobel Prize for Medicine to Sir John Gurdon of the UK and Shinya Yamanaka of Japan. They discovered that mature, specialised cells – that is, the normal cells that make up our body – can be reprogrammed to become immature stem cells – that is, ones capable of developing into any tissue of the body. For example, human skin cells can be reprogrammed to become stem cells, and then form nerve cells, or heart muscle cells and so on. This discovery caused textbooks to be rewritten and has created new opportunities to study diseases and develop new methods for diagnosis and effective therapy. These reprogrammed cells are called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and, together with embryonic and umbilical-cord blood cells, comprise the three main types of stem cell capable of developing into other cells.

The two stem-cell treatments so far

The only stem-cell therapies currently approved by America’s Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are the use of cells from bone marrow or umbilical-cord blood. Both are rich in blood stem cells that can be used to treat cancers of the blood and bone marrow, together with certain inherited or acquired bone-marrow or immune-system disorders.

There are some extraordinary examples of lives being saved by bone-marrow transplants. The procedure involves removing the patient’s stem cells and replacing them with stem cells from a matching donor. These then attach themselves to the patient’s bone marrow and start making new blood cells. (The donor’s transplanted bone marrow is replaced by the donor’s body in four to six weeks.) A few years ago a radiographer at Sheffield hospital who had joined the bone-marrow registry was told she was a match for a nine-year-old boy in Chile with a rare form of leukaemia whose only hope of survival was a bone-marrow transplant. She agreed to donate and his life was saved. Since up to 70% of patients with leukaemia or lymphoma do not have a match within their family, lives are saved by finding someone else who is a match.

Subscribers can read it in the digital edition or app