This article is taken from our FREE daily investment email Money Morning.

Every day, MoneyWeek’s executive editor John Stepek and guest contributors explain how current economic and political developments are affecting the markets and your wealth, and give you pointers on how you can profit.

MoneyWeek’s head honcho, Merryn Somerset Webb, and I are both doing shows up here in Edinburgh at the Fringe Festival this month.

And we are both doing shows at the house where Adam Smith lived for the last 12 years of his life, Panmure House – in the very room where he completed The Wealth of Nations, and where he would welcome great intellectuals, who he invited to discuss and debate the great issues of the day.

As a result, I’ve been swotting up on my Adam Smith, and today I thought I’d tell you everything you need to know about the father of economics.

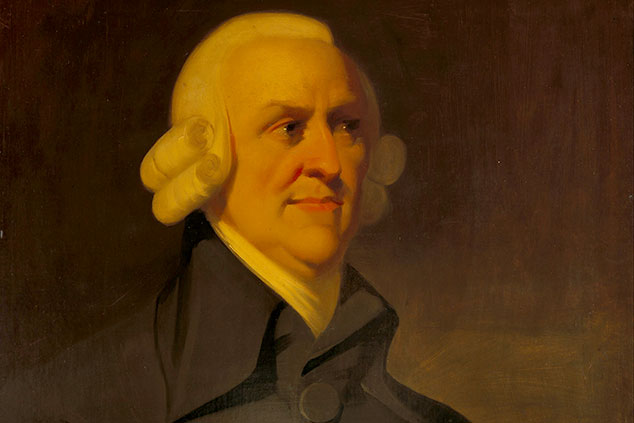

The life and works of Adam Smith

Scottish philosopher Smith, who lived between 1723 and 1790, is best known for his two books – the Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1759, and his magnum opus, an Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (thankfully, now abbreviated to The Wealth of Nations) which took him more than ten years to write and was eventually published in 1776.

Why is he so important and so revered?

Economist Eamonn Butler, who founded the Adam Smith Institute think tank, answers that question when he says: “The Wealth of Nations is one of the world’s most important books. It did for economics what Newton did for physics and Darwin did for biology.”

The Wealth of Nations is seen as the first book of economic theory, hence Smith has been nicknamed the father of economics. As Smith largely argued for free markets, non-intervention and clear and simple taxes, he is also nicknamed the father of capitalism. Many of his ideas are still highly pertinent today.

He was born in Kirkcaldy, on the other side of the Firth of Forth from Edinburgh, in 1723. His father, a customs officer, died before he was born, and so Smith was brought up by his mother. In fact, she actually lived with him in Panmure House, before she died at the ripe old age of 92. He never married.

He was educated at Glasgow University and then won a scholarship to Oxford University, about which he quickly developed a low opinion. “The greater part of the public professors have, for these many years,” he said, “given up altogether even the pretence of teaching.” (Given some of the “woke” antics I read about going on there today, it seems little has changed.)

Largely self-taught, he left Oxford early – in 1746. By 1748, he was lecturing and in 1751 became a professor at Glasgow University. When he published the Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759, it became so popular that students from all over the world enrolled at Glasgow to be taught by Smith.

How Adam Smith secured a massive defined-benefit pension

One such fan was the Duke of Buccleuch’s step-father, Charles Townshend, who would go on to be chancellor. (His Townshend Acts, which taxed and regulated trade with the US, especially taxes on glass, paint, paper and tea, became extremely unpopular in the US. If Americans were to pay these taxes, they wanted representation in the British parliament. We all know what happened next).

Townshend hired Smith as a tutor to escort his stepson, the young Duke of Buccleuch, on an educational journey through Europe. The salary was £300 per year plus expenses – double what Smith got at Glasgow – plus a £300-per-year pension. It was effectively a lifetime salary, and it was too much for Smith to turn down.

In France, Smith met with the likes of Voltaire, Benjamin Franklin and other great Enlightenment thinkers, but, their stimulus aside, he started to grow bored and began working on another book to while away the hours. It would become The Wealth of Nations.

He returned to the UK in 1766 and spent the next ten years working on his magnum opus. On publication it was an instant success.

Shortly before he died in 1790, he had all his unfinished work destroyed. It is believed he had been working on two new treatises.

On his deathbed, he expressed disappointment that he had not achieved more.

As for his character, it seems Smith was your classic absent-minded professor – eccentric and good-willed. He was forever being seen talking to himself. He had a smile of “inexpressible benignity”, said his friend Dugald Stewart, and “peculiar habits of speech and gait”, said a biographer.

On one occasion he took Townshend on a tour of a tanning factory, and became so enrapt in a speech about the merits of free trade that he didn’t notice a tanning pit, full of noxious substances, right in front of him, and walked straight into it. He then needed help getting out.

On another occasion, he went out walking in his nightgown and ended up 15 miles outside of town, before some church bells brought him back to reality, and he had to quickly make his way home.

He also had quite a self-deprecating sense of humour. To explain why he avoided sitting for portraits he said, “I am a beau in nothing but my books.” (There is only one portrait of him made in his lifetime – actually an enamel medallion, by James Tassie).

He remarked to James Boswell (Samuel Johnson’s biographer) that his conversation was so unimpressive that speaking about his ideas might reduce the sale of his books.

And he quipped to the painter, Sir Joshua Reynolds, that he made it a rule when in company never to talk about anything he understood.

So there you go – the life and character of Adam Smith. Next week I’ll outline some of his main ideas. And if you’re up in Edinburgh this month, come and see one of the shows at Panmure.

There’s my lecture about the history of the Fringe, and its relationship with the teachings of Adam Smith – that’s Adam Smith: Father of the Fringe.

Or you can discuss the big issues of the day with Merryn, me and guests from the world of politics, economics and finance. That’s The Butcher, The Brewer, The Baker and the Commentator. I host from 7-16 August, Merryn hosts 17-25 August.