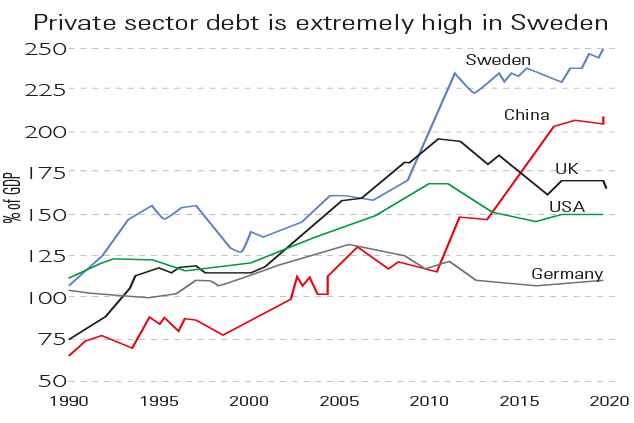

The Swedish central bank, the Riksbank, “pioneered” the use of negative interest rates after the financial crisis, charging banks for keeping excess reserves with it from as early as 2009. In early 2015, it cut its main policy rate, which eventually sunk as low as –0.5%. The bank’s goal was to prevent the Swedish krona from becoming too strong, thus hurting growth. But its drastic action also fuelled a housing bubble, which has driven private debt in Sweden to extraordinary heights, as the chart shows. As a result, the bank is changing course – rates are now at –0.25% and it hopes to raise them to 0% in December. “Investors should take note,” says Nick Andrews of Gavekal. “The Swedish canary may be signalling a shift in attitudes to negative rates.”

Viewpoint

“After we’d sold [the Woodford Equity Income Fund], we had a policy here to say absolutely nothing about why we had sold it… we were really very worried that there would be a run on the fund. We realised that if there was a run on the fund bad things would happen and that is exactly what has happened and we didn’t want anything to do with that… We had lost confidence with what was happening with the fund. When we had started there were six unquoteds in the fund and by the time we’d sold there were 45… You effectively had a situation there where someone was effectively and certainly by the end… pushing [the rules] to the absolute limit… I think it would be fair to say that if he had worked at Jupiter it just wouldn’t have happened. For that matter, it’s arguable that’s why he left Invesco, I don’t know.”

Jupiter’s John Chatfeild-Roberts, quoted in Citywire, on why the fund group sold out of Neil Woodford’s fund by late 2017